|

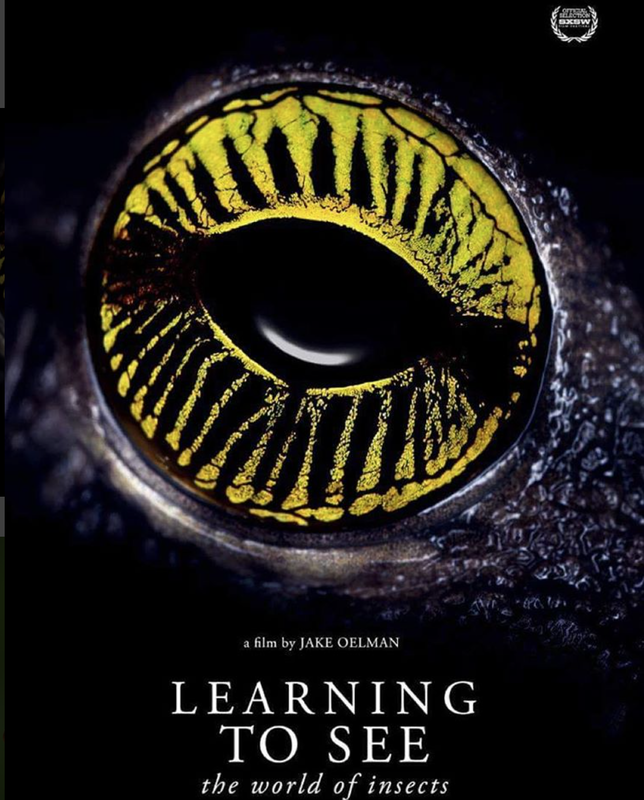

Jake Oelman film explores the world of exotic bugs, habitat depletion, and a father-son relationship

Insects wound up taking Jake Oelman's father away from him. But in the end it was insects that brought them back together.

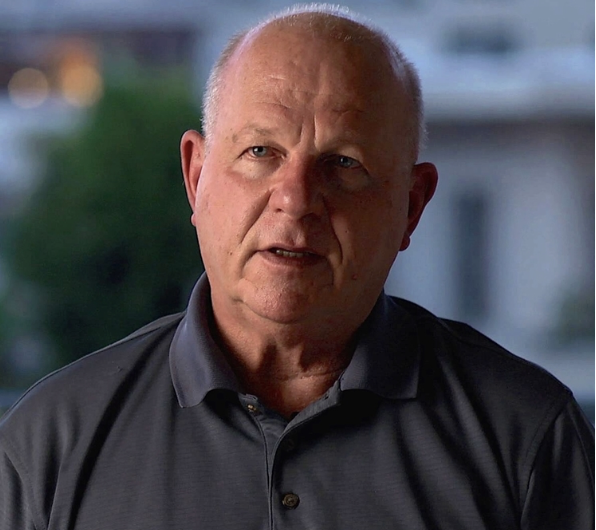

For the past 20 years Oelman's father Robert has devoted his life to photographing exotic bugs in the Amazon rain forest, leaving behind a career as a psychologist. The geographic separation didn't provide much opportunity for father and son to see each other in person, but that changed when Oelman decided to make a documentary about his dad's work. They’re special in their form, in their evolution process and in kind of what they have done to try to survive individually and as a species.

Jake Oelman's film, Learning to See, premiered on Sunday at the SXSW festival in Austin.

"After more than twenty years of traveling, searching and photographing, [Robert Oelman's] quest culminates with a New York City gallery show," SXSW said of the film. "He also learns that these tiny life forms must continue to survive. They are at the bottom of the mammalian food chain and are critically important to all animal species including mankind."

Nonfictionfilm.com spoke with Oelman about SXSW, the environmental message of his film and his relationship with his father.

How has your SXSW experience been? Jake Oelman: Incredible. When you have a film and it premieres at such a wonderful event and kind of marquee venue, if you will, it’s hard to describe but definitely very special. What are your early memories about dealing with insects? My brother and I were fascinated with bugs as kids. We put them in cigar tubes. I feel quite guilty about what I did to them. JO: When I was four years old or five years old I remember getting stung in the backyard on the bottom of my foot by a bee and it just was extremely painful. It kind of scared the crap out of me. I think I’m not alone in that -- like many people, throughout my life my interaction with insects and my viewpoint of insects was from the place of "these are household pests, they’re scary, they’re going to bite you,” this type of thing. But as my dad started to do his work and I started to see it my vantage point really changed and changed dramatically... My dad was able to really open my eyes to what’s out there and change my point of view, which is really cool.

In the film you’re dealing with some quite exotic species of insect. What is it like to be face-to-face with these creatures? The more you look at them the more fascinating they are.

JO: In the beginning of shooting I would be a little bit squeamish. But once you really start to look at them and see their behavior and how they interact with other insects, how they interact with people and really kind of examine the details — the facial structures, and kind of the personalities of the various different types of insect — then you really do have a deep appreciation for it because you’re realizing that you’re seeing things that are not pests and that are really special. They’re special in their form, in their evolution process and in kind of what they have done to try to survive individually and as a species. It was eye-opening. It was humbling and ultimately very cool.

And so it’s a very humbling experience to be in the presence — to kind of hold a praying mantis in your hand and to have it look at you and to have it interact with you and you’re like, wow, this is this kind of intelligent life form that I never really would attribute those type of things to, this very small creature. It was eye-opening. It was humbling and ultimately very cool.

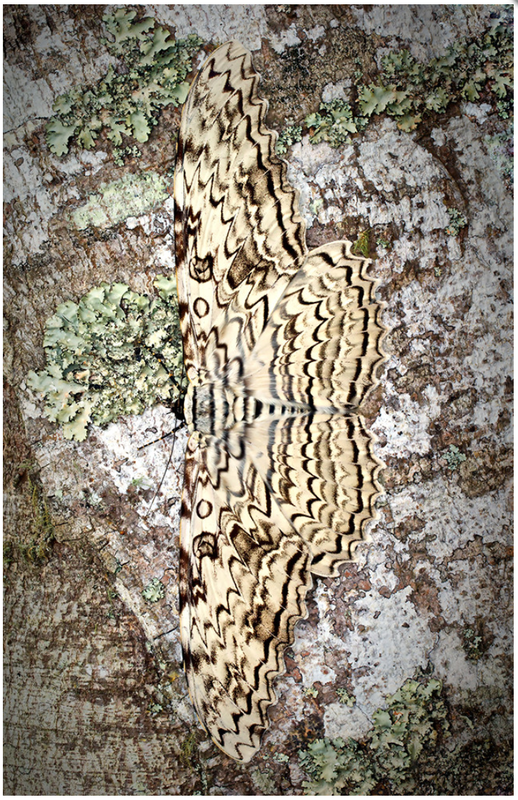

Amastris sp.II tree hopper, photographed in Ecuador by Robert Oelman. From Robert Oelman's website: "Order Hemiptera and family Membracidae, this is a mottled green and yellow treehopper which is probably a new, unclassified species. Treehoppers are small, 2 to 10mm in length, phloem-eating insects that have a straw-like mouth that pierces plant stems."

In some sense your documentary is the quintessential nature film — “let’s have a gander at these insects." But it’s more than that — it's also about what’s happening to their environment and what we don’t know and, I suppose, the danger of ignorance.

JO: Honestly, when I first started out [on this movie] I was looking to do more of a short subject on my dad because I was inspired by a person’s ability to change.. As the film progressed it just became this larger film with a lot more scope. The title “Learning to See” is exactly that. We’re seeing it through my dad’s lens but at the same time it really applies to everything. If you can open your eyes and just look around and see your environment, be aware of your environment and learn about what’s in your environment you will develop an appreciation for that. We’re battling huge corporations that have all the money and are just gobbling up all the natural resources at an extremely rapid rate. It’s important to see that the planet cannot necessarily sustain that type of growth and abuse forever and these are things [creatures in the natural world] that have been here long before we were and we need to value that and appreciate it. So hopefully people get that message when they watch the film.

What age were you when your father decamped to South America, as it were?

JO: I had just gone off to college so I was 18 at the time. For me, it sort of seemed like my dad was going on an adventure. I didn’t know that he was going to stay there for 20 some odd years and not return, but it also seemed kind of cool from my perspective. But I think probably other people in the family might have thought he was a little bit crazy, going like, “Why in hell are you moving to Colombia? I mean Pablo Escobar, there’s kidnapping, there’s drugs.” And I was like, “Oh, hey, you’re going on this adventure! Cool, man! That’s really cool!” So it wasn’t like he was leaving his family behind. We kept in contact very often and I would get these wonderful letters where it just felt like he was kind of born anew when he moved there. I mean it took a while before he really got into the photography thing but I just knew as soon as he went there he was starting to kind of enjoy life more.

The experience of making the film with him — what was that like for father and son? I’m sure you got a lot closer working on it.

JO: We definitely got a lot closer. I think that if you can successfully pull off a film about a family member you could probably pull off about anything. In the beginning it was very hard. I think that my dad was a lot more closed off when we started. I wasn’t sure — and he’ll tell you the same thing — I don’t think that he necessarily trusted me in the very beginning. As I kind of hit these milestones of doing a Kickstarter campaign and then raising more money and shooting interviews with various scientists and getting pretty footage and starting to do rough assembly he became more and more trusting. And as the film progressed he really opened up in talking to me about his experience of what he was working on. So that was really cool to watch him sort of personally blossom because this is definitely not the same person that I grew up with. It was a great bonding experience

Although I didn't treat insects very well as a child, I now go out of my way to extract a bug from my house without harming it, if I find a spider, for instance. I won’t kill a silverfish or anything like that. What is your approach to insects now after the experience of making this film?

I think I’m the same way. The day before I left for South By there was a cricket in my bedroom and it’s like my first thought is, “Okay, let me empty out a water glass jar, get a piece of paper, you know, capture it so I can bring it outside. And I feel that way about a lot of insects. One time when we were shooting in Ecuador my wife came with me and she was working with us. There was this really kind of cool beetle that we had been photographing and it got really tired. After we let it go the beetle was just too tired and then all of a sudden — we were kind of watching it trying to fly away -- these ants fully attacked it and killed it. And honestly we felt really bad about it. Most of the time everything we photographed we were able to release back into the wild. Insects are very fragile and we felt like this responsibility that we had kind of let this beetle go. I felt it. I could see the kind of pain on my wife’s face that here’s this beautiful insect and it got devastated. So there’s a lot more feelings of compassion and empathy for just all of nature really, whether it’s a big cat, a tree, or a tiny beetle. The interaction and the experience of working with the insects [during filming] has really changed our perspective. It’s kind of refreshing, you know. It’s cool to have your eyes opened in that way. |

AuthorMatthew Carey is a documentary filmmaker and journalist. His work has appeared on Deadline.com, CNN, CNN.com, TheWrap.com, NBCNews.com and in Documentary magazine. |

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

Proudly powered by Weebly

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

RSS Feed

RSS Feed