Absorbing new doc short on Mr. Toledano: artist going to incredible lengths to confront his fears10/15/2016

If you have 25 minutes to spare, watching The Many Sad Fates of Mr. Toledano is a fascinating way to spend them

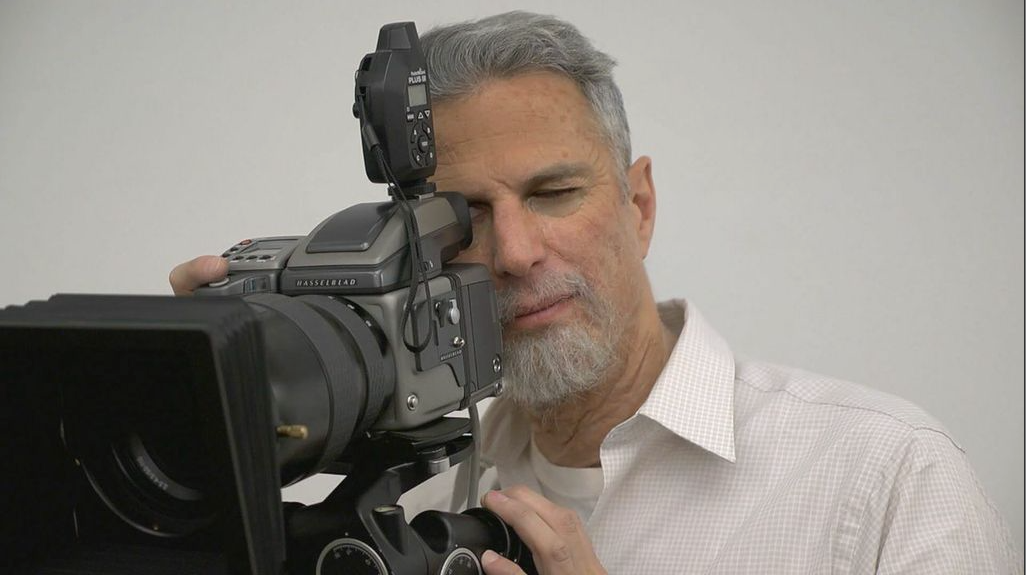

Director Akira Kurosawa once said, "An artist never averts his eyes." Photographer Phillip Toledano seems to have taken that to heart.

For three years he delved into his deepest fears over what might happen to him as he aged -- the kind of anxieties many of us share but from which we avert our gaze. Mr. Toledano (as he likes to be called) went there, in a way befitting such an original artist. He wanted to dive into what possible fates awaited him... The project was about the darkest things that he could fathom.

Joshua Seftel's new short film, The Many Sad Fates of Mr. Toledano, documents the searing process Toledano put himself through. It involved spending countless hours in a makeup chair being transformed into possible future selves: stroke victim, homeless man, alcoholic, doddering old-timer, suicide.

The documentary, which runs just under 26 minutes, recently joined the lineup of New York Times Op-Docs, a prestigious series of short films made available online free of charge.

SHARE THIS:

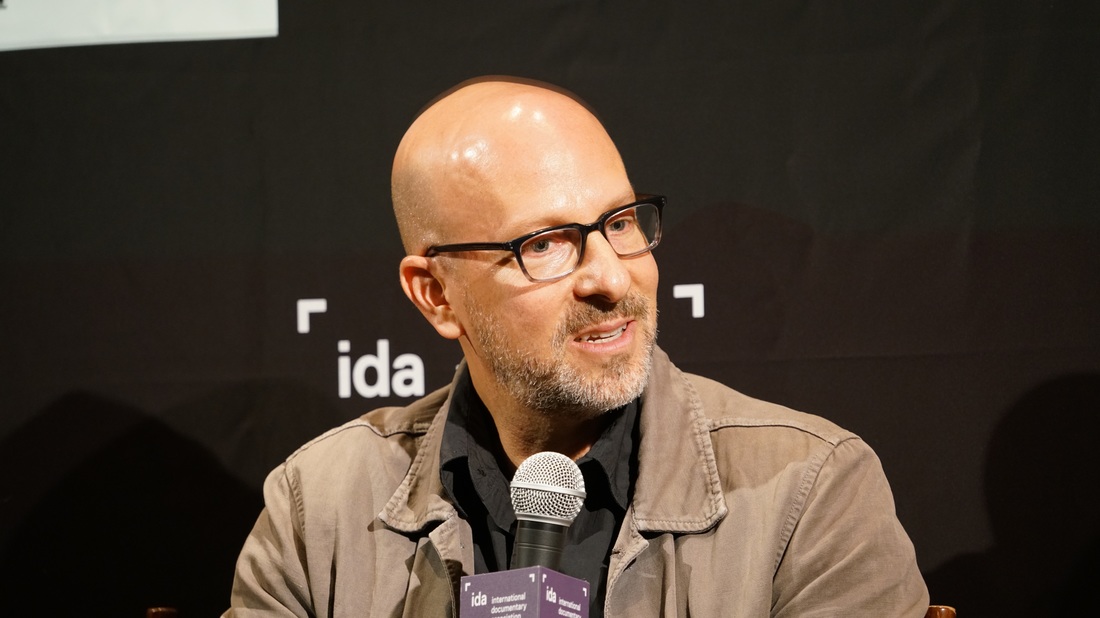

Nonfictionfilm.com spoke with the director about his short and whether Mr. Toledano's project constitutes an act of bravery.

Nonfictionfilm.com: How is the film doing online so far? Joshua Seftel: It's not a typical Op-Doc but it seems to be reaching audiences in a successful way. It's been a popular Op-Doc which makes us very happy. NFF: Your relationship with Mr. Toledano goes back quite a ways. JS: Philip Toledano is an old friend of mine. We went to college together and remained friends. He's a very accomplished photographer based in New York. His work ranges from well-known magazine covers to a great body of work as an artist. He's actually quite popular and well known as an artist in Germany. We joke that he's the David Hasselhoff of photography because he's better known in Europe than he is in the States.

NFF: How did your collaboration with him on this film came about?

JS: When I ran into Phil on the street by chance about four years ago, his father had passed away not too long before that. And my father had also passed away and we were sharing about that and talking about grieving and dealing with the loss of a parent. And then he started to tell me about this project he wanted to do which involved DNA tests and psychics and special effects makeup. I just immediately said, "Hey, this sounds like a great thing to film." And he was interested in that so he allowed me to film him. He wanted to... kind of define the fears that he felt about his future.

JS: I thought it was going to be a few months. It turned into three years. From my vantage point, I think what he was setting out to do was to kind of take a deep dive into the future in some kind of futile way. He wanted to dive into what possible fates awaited him and that meant going to psychics, finding out ideas of what could happen, getting a DNA test, and then sitting in a makeup chair for four hours at a time being made up into these possibilities like having a stroke, becoming obese, dying -- all kinds of possibilities that could befall any of us.

NFF: As the title of your film suggests, the possibilities that he's exploring are not what you'd call optimistic. JS: The project was about the darkest things that he could fathom because that's where he wanted to be. That's what he wanted to be thinking about and focusing on. Maybe trying to catalogue his fears by portraying them.

NFF: How courageous was it for him to go to those dark places? Most of us try to avoid that.

JS: I think Phil would agree with this -- I don't think it's incredibly heroic to put on makeup and pretend to have a stroke. I do think that a lot of us spend a lot of time trying not to think about these sorts of things. We try not to think about the negative things that are going to happen to us. Every once in a while those thoughts might slip through and then we push them down or tuck them away. The fact is that some of these things are going to happen to all of us. He chose to do the opposite of what we're maybe trained to do. He chose to say, "I'm going to look at these things. I'm not going to deny that they're going to happen. I'm not going to pretend that I may not get sick and old and be alone or become delusional in some way." It's an exploration of the things that we are in our society and our culture are kind of taught not to go there. And so is it brave? Is it heroic? I don't know. But it's interesting. Some people are really disturbed by the photos... Other people are really intrigued...

NFF: This project was a kind of therapy for Mr. Toledano, but one with an uncertain outcome. His wife was clearly concerned that it would plunge him into an existential despair.

JS: Maybe that's where he was heroic. He did the project despite his wife urging him not to. Or maybe that was cowardly, I don't know. I don't want to judge the project. I think that's the risk [experiencing existential despair]. Different people look at these photos or look at the film in different ways. Some people are really disturbed by the photos and think the project is maybe like indulgent and too negative. Other people are really intrigued by the photos and the film and relate to it. Some people have written to us about how helpful the film was for them because they were grappling with these things. And so I think there's a continuum and there's a dialogue that we all have with this stuff around mortality... We're all going to have to face it, both in the loss of our loved ones and in our own eventual demise. I think the film in some small way contributes or examines that dialogue that all of us have.

NFF: Does Mr. Toledano seem different to you after this project? Do you see a change in him?

JS: Every time I filmed him, for three years, I would say, "So are you almost done yet?" And he'd say, "No, not yet. I need to do more. I need to do more." And then one day -- I remember it was the day that he enacted his suicide in the bathtub -- I asked him, "So, are you almost done?" And he kind of just stopped for a second and he said, "You know what. I think I'm done." Something happened, something inside him said, "You don't need to do this anymore. Maybe you've explored enough." I don't know if it was the passing of time that did that or if it was the actual exercise of looking at all these images. To me what I found interesting about his project -- and I think one of the reasons that I was interested in making the film -- was that I watched all these images compile. I watched that dining room in their house fill with photographs. And there was something about being able to make those [fears] concrete, to transform the anxiety that I think all of us have somewhere deep down, this anxiety about our future; to actually give it some shape -- even if it was a partial shape, an inaccurate shape -- perhaps has some value in helping one to contend with this thing that we all have to contend with.

NFF: To make the photographs involved acting, it seems to me. Mr. Toledano is playing a character in each of the scenarios. You see him shuffling down the street as the homeless guy, for instance.

JS: I shot this but it didn't make it into the film. He actually took acting lessons. He went to this guy and would get lessons and the guy taught him how to feel pain and how to be old... The acting lessons were very interesting. I enjoyed watching those.

|

AuthorMatthew Carey is a documentary filmmaker and journalist. His work has appeared on Deadline.com, CNN, CNN.com, TheWrap.com, NBCNews.com and in Documentary magazine. |

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

Proudly powered by Weebly

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

RSS Feed

RSS Feed