|

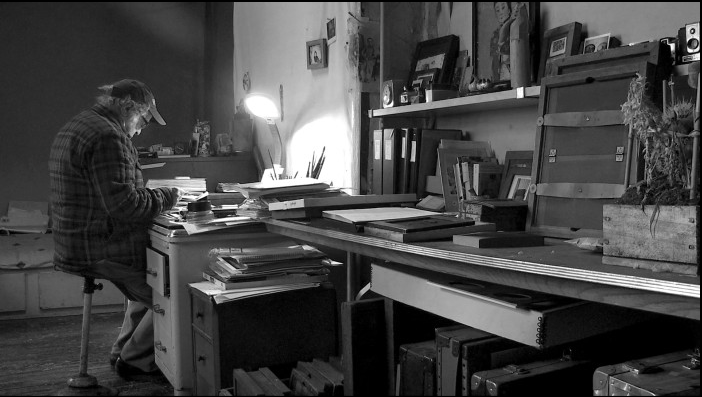

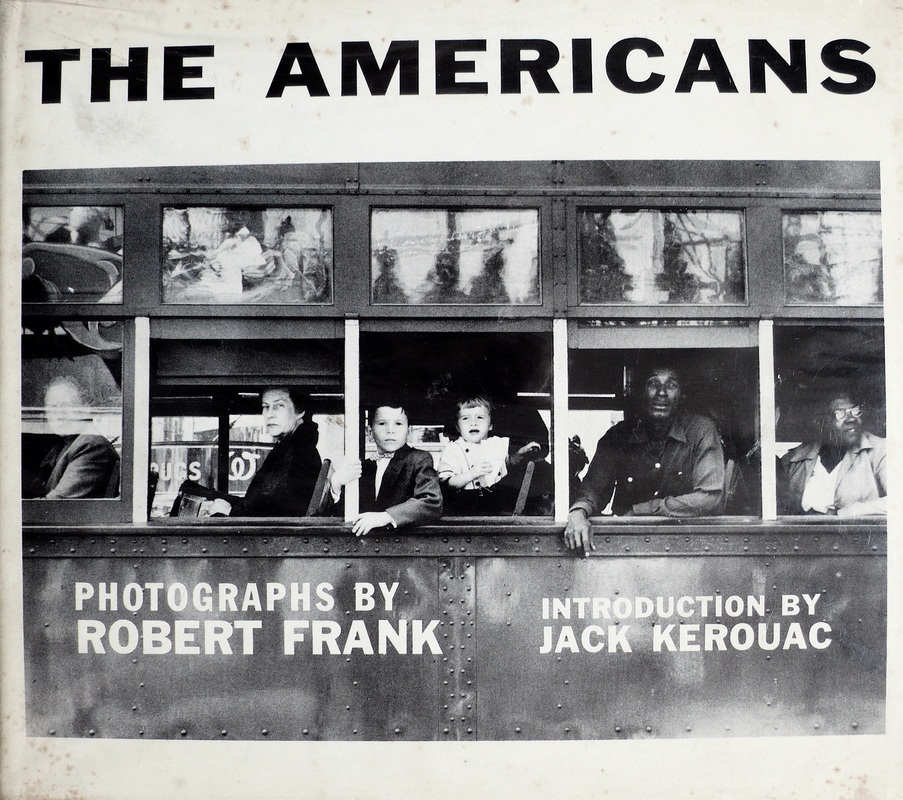

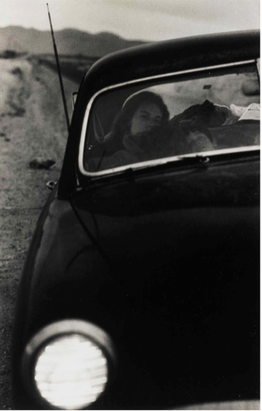

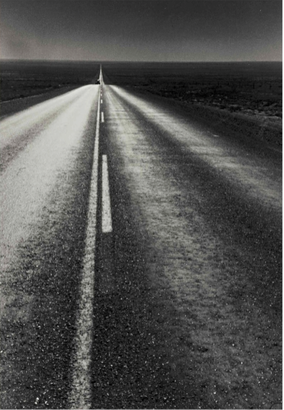

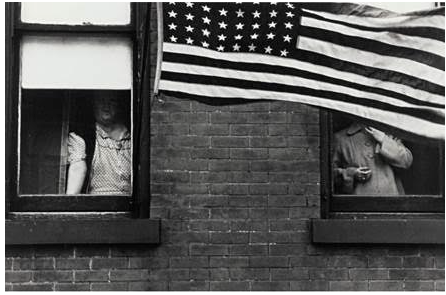

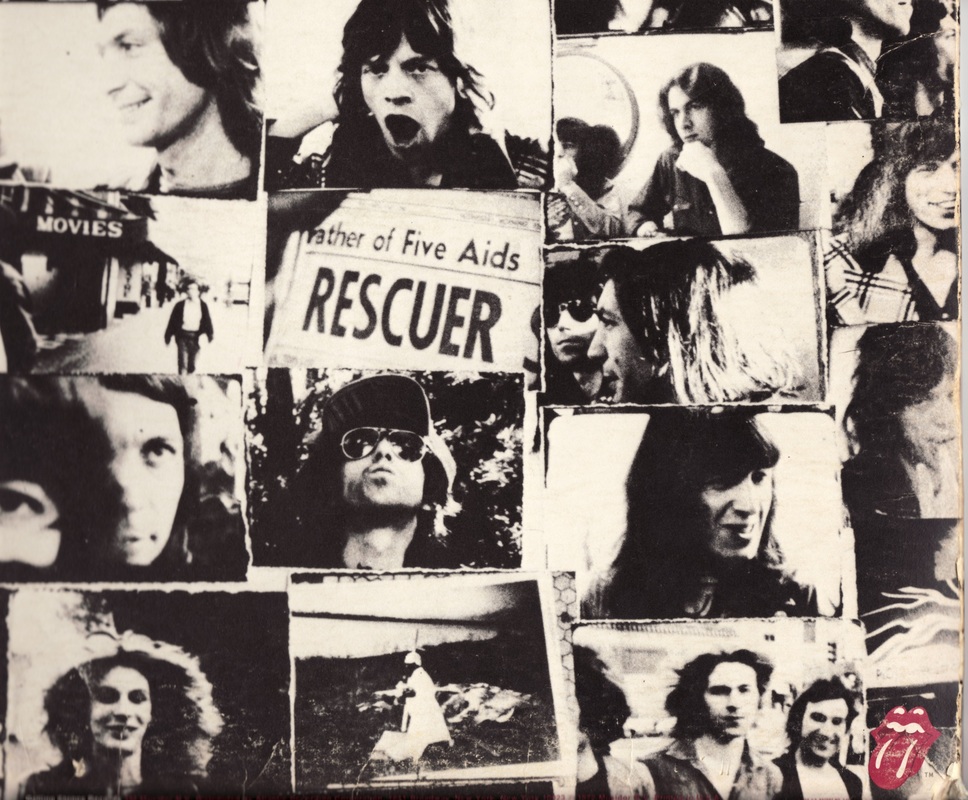

Laura Israel directed the movie on the man behind Cocksucker Blues and The Americans More than 50 years ago Robert Frank published a book of photographs that changed the way Americans viewed themselves. Later he made a documentary about the Rolling Stones that became the stuff of legend. With achievements like those you might expect Frank to be a kind of eminence grise, a man steeped in his own importance. But he comes off as anything but in the documentary Don't Blink -- Robert Frank, directed by his friend and collaborator Laura Israel, which screened in the Panorama section of the Berlin Film Festival. He’s quick. Somebody called him a gunslinger with a camera, which I love. Frank at age 91 is surprisingly mischievous and engaged with the world, with an observant eye that still captures what others miss. "Sometimes I’m with Robert and he sees these things and he mentions them and they’re things I didn’t even notice, that people don’t even notice," Israel told Nonfictionfilm.com. "He’s just always looking." In 1958 the Swiss emigré published his seminal work, The Americans, a collection of 83 photographs culled from thousands he took while traveling the United States. It generated controversy for images that to some viewers starkly portrayed America's extreme racial divide. However, the book eventually came to be regarded by many as the most important American work of photography in the post-war era. From there, Frank turned his attention to filmmaking with similarly historic results. His 1972 film, Cocksucker Blues, chronicled the Rolling Stones U.S. tour in support of the album Exile on Main Street. Famously, the band sued to prevent release of the film, fearing its intimate glimpse into their intense partying would harm the Stones' reputation. Israel was already deeply familiar with Frank and his work before embarking on the documentary, having edited his films for past two decades. Nonfictionfilm.com spoke with her in Berlin about her fast-paced and endearing portrait of the artist. Nonfictionfilm.com: You take a non-standard approach to revealing Frank's essence as a person and creative force. This is not your typical biographical documentary. Laura Israel: I think personally that films should embody the feeling of what you’re trying to convey. So the form should actually follow that. And that’s what I went with because Robert is from the Beat generation and because his films and his photographs have a certain feeling and emotion, and like a rawness to them -- the film about him should also have that too. A lot of films about photographers seem very still and very slow and I kind of wanted to break that mold and make it move quickly and have an energy to it. I think Robert Frank has that energy and his work has that energy and I made a film to go with that. NFF: There's something, I don't want to say "inspiring" about Frank because that sounds so -- LI: I’ve said “inspiring” like 30 times in the last three days so I’m trying to stop that myself [laughs]. NFF: If you're asked to sum up what Robert is like, how do you respond? LI: “Spontaneous intuition.” He says that in the film but I really think that just off the cuff he does what he wants. And of course that’s a challenge for shooting somebody because some days you go there and he says, “I don’t feel like doing it today.” And then we said, “Okay, we’ll go have a cup of tea.” I kind of enjoy that sort of honesty and that sort of, you know, “I live my life and I do my work the way I want.” Not compromising. I don’t think people know what a sense of humor he has. And his friends and people that I know that are close to him said, “I’m so glad that you got his unique sort of dark, cynical sense of humor.” NFF: It's remarkable what he captures with his camera, these arresting, candid images. LI: Robert just looks. He just sees things. There’s a quote from him saying, “You have to see things that other people aren’t seeing.” There was an instance in Paris where there was a blind man selling flowers and people just walked by him and just ignored him and Robert took all these pictures of him and they’re beautiful but it’s like, yeah, you have to see something that other people don’t see and in order to do that you really have to look. Sometimes I’m with Robert and he sees these things and he mentions them and they’re things I didn’t even notice, that people don’t even notice. He’s just always looking. NFF: What is extraordinary about the photographs is that his eye is so open. He often is taking pictures of people who were essentially the objects of disdain by the society of that time, but his camera is generous. LI: Totally. Some of the archival [footage] that we got was of Allen Ginsberg in the 80s and one of the things that he said, that ended up on the cutting room floor but that I thought was really nice, is that Robert sees all human beings as the same. They all have the same stature. NFF: Recently Sotheby's auctioned prints of some of Frank's photographs from The Americans that were in the collection of a couple in Los Angeles, generating over $3.7 million. Christopher Mahoney, the Sotheby's VP for oversaw the auction, told me Robert was aware of the auction but he wasn't benefitting financially from it. LI: Not a lot of people know that the photographer doesn’t necessarily get that money. It goes to the collector. Probably the photographer sold those prints for quite a small amount of money at the time... At one point [decades ago] MOMA was selling [famous photographic prints] for like 50 dollars... He was on the cusp of when things changed from being very cheap to being a lot more expensive. Photography in the beginning was not respected as an art form either. And then all of a sudden it takes off and it takes off really quickly. And I guess he was in the middle of that. NFF: After The Americans was published, Frank rather abruptly switched his focus to filmmaking. LI: He said it somewhere else, “I love difficulties and difficulties love me.” He also said in another interview that it was like walking into another room and you see what’s in the other room and then when you walk back into the first room you have a different feeling, or it gives you a freshness. So I think that going to filmmaking made him after a while more interested in photography as well. What I set out to do was a film about Robert as a filmmaker rather than a photographer because I thought people know him as a photographer so filmmaker would be more interesting. But when I first started talking with him he talked about them interchangeably -- photography and film. And I realized that he used a lot of film in his photography and a lot of photography in his films. So for him the medium is not what he’s interested in. It’s his feeling and trying to convey that feeling and using every tool you have to do it. NFF: You were able to use some footage of Cocksucker Blues. How did you work that out? The film has never officially been released. LI: I think it's a great film and it was nice to be able to use that... The Super 8 footage is the footage that was used for the Exile on Main Street [album art] where Robert just took out little frames and then made the cover out of it, which is sort of an interesting technique when you think about when that was done, back in the day. LI: We did get permission to put some of Cocksucker Blues and a Rolling Stones song in the film and that had a lot to do with our music superviser, Hal Willner, who’s amazing, who knows everyone and just calls them up [laughs]. NFF: There is a corollary between editing your film and the kind of editing Frank did for The Americans. Out of the thousands of photographs he had taken, he narrowed the book down to just 83, an incredible task. LI: We spent two days looking at the contact sheets for The Americans… It’s amazing to see how many good pictures— not just good pictures, great pictures — didn’t get chosen. But it’s very important for him to tell a story, to tell a full story in a small book, rather than having it be a big book that’s overwhelming and then having photographs that don’t tell a piece of the story that he wants to tell… He tries to tell a story with the photographs. Not necessarily a story with a beginning, middle and an end but a story about the feeling of being there, the feeling of what this subject is. NFF: Has Robert seen the film? If so, what was his reaction?

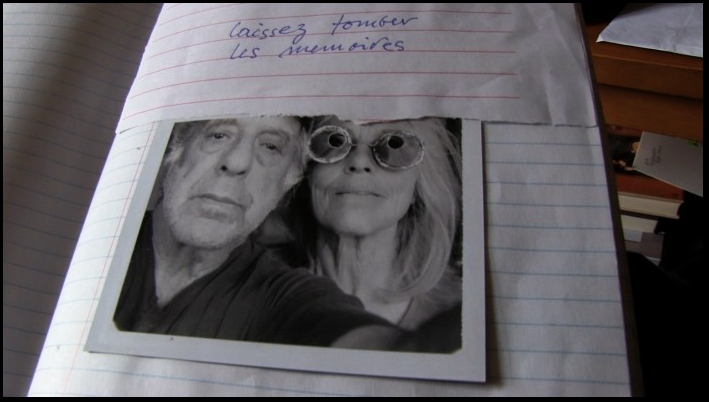

LI: At one point I showed him like maybe a five minute [segment] which ended up being the first five minutes of the film and he just said, “I trust you implicitly. Just keep going. You’re going in the right direction.” And then when I showed him the film— him and his wife June — it was really kind of a weird situation because they don’t have any technology in their house, so I had to bring my laptop and my speakers and an extension cord. And they didn’t have a three-prong outlet and it was like this whole thing. But then finally we sat and watched it and they really enjoyed it. So I was very happy because it’s a tough room, that room! [laughs]. He’s so into control and we had actually taken a lot of liberty with the photographs and repositioning them. I was nervous about that. But he said, “Oh, you made them come alive. It’s a different medium, film. You had to do that.” So I said, “Okay, cool. Yeah, that’s the reason we did that.” [laughs] |

AuthorMatthew Carey is a documentary filmmaker and journalist. His work has appeared on Deadline.com, CNN, CNN.com, TheWrap.com, NBCNews.com and in Documentary magazine. |

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

Proudly powered by Weebly

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

RSS Feed

RSS Feed