|

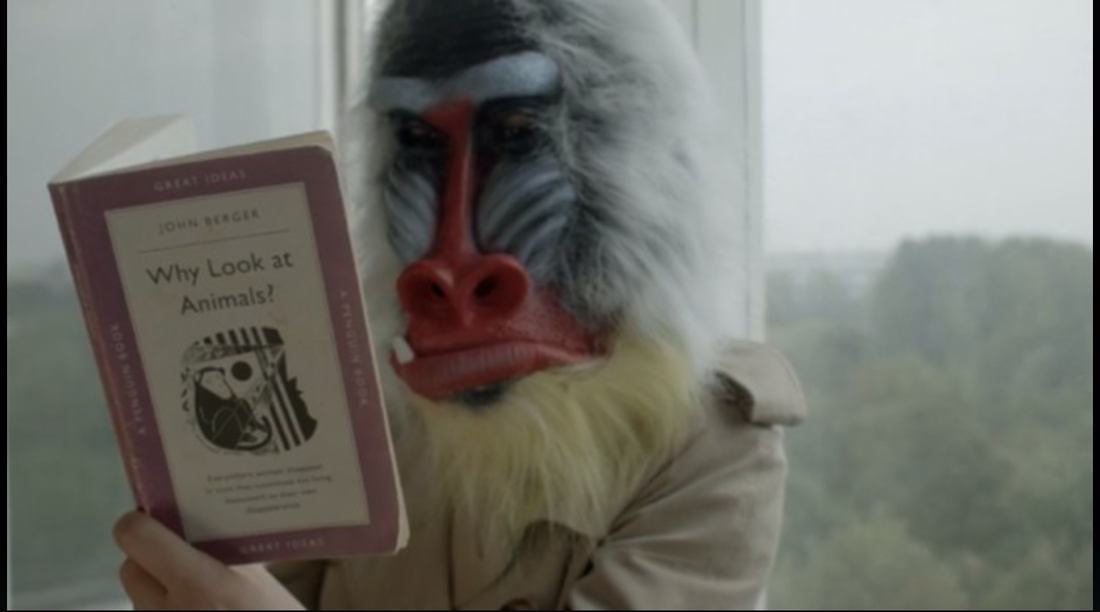

The actress directs one of four essay films on the vital British author-filmmaker-artist There was something deeply inspiring about the Sundance Film Festival, which now finds its echo at the Berlinale: films by and about men of a very advanced age who continue to engage profoundly with the political and artistic questions of our time. D.A. Pennebaker, age 90, brought a new film to Sundance, Unlocking the Cage [co-directed with his wife Chris Hegedus], exploring the "personhood" of animals. Norman Lear, 93, came to Sundance too, as the subject of the documentary Norman Lear: Just Another Version of You. On Sunday night at the Berlinale, Laura Israel premiered her new film Don't Blink -- Robert Frank, a documentary on the 91-year-old photographer and filmmaker whose 1958 book, The Americans, is considered one of the seminal works of photography of the 20th century. And then there is John Berger, at 89 the youngest of the aforementioned figures. The British-born writer-artist-filmmaker is the subject of The Seasons in Quincy: Four Portraits of John Berger, which premiered at the Berlinale on Saturday. Actress Tilda Swinton, a friend of Berger's who appeared in the 1989 film Play Me Something which Berger co-wrote, directed one of the four portraits of him. The other three are directed by Colin MacCabe, Christopher Roth and Bartek Dziadosz. "I think John’s a very inspiring figure. I mean he was an inspiring figure to me when I was young, when I was a teenager," MacCabe said at a roundtable discussion with journalists in Berlin. "Some people you meet and they’re not quite as inspiring as their work. And some people you meet and they’re even more inspiring than their work. And John is certainly the second category. And he has kept on thinking... I mean he’s kind of endlessly productive across an incredible range of writing, photography, filming, painting, drawing, writing novels, writing reportage. He’s a great man." Berger was born in Britain but has lived since the 1970s in what might be called a kind of self-imposed exile -- albeit an idyllic one -- in Quincy, a rural town in the mountainous Haute-Savoie region of France. That is where the interviews for the film took place. "That landscape is as much a protagonist of this film as he is," producer Lily Ford said at the roundtable. She said Berger chose to live there "for these very specific reasons that were to do with his curiosity 40 years ago about the kind of way of life that was being lost as people migrated to the cities." Roth was quick to point out that Berger's motives for relocating did not imply a rejection of modernity. "He didn’t go back to nature or he didn’t kind of do it because he believes in Mother Gaia or all that shit. But he kind of wanted to live the peasant life because he wanted to try to report it, to write about it. And he’s also very much a modernist or Marxist," Roth said. "It’s always interesting because the movement [with him] is always forward and never backwards. It’s not a conservative idea that 'we hate technology and that’s why we live in the woods.' It’s the contrary and that’s so good. And you can still talk to him about the Internet and whatever you want. He’s interested. He’s really interested." Berger's political philosophy, sometimes described as Marxist-humanist, made him a hero to the left. Not unlike Howard Zinn in the U.S., artists tended to gravitate toward him in part because of his politics but also for his generosity of spirit. Generous, yes, but he did stipulate some conditions for the filmmakers. "John didn't really want to talk about his past, about his writing," Dziadosz said. "And you can imagine that is a bit of a problem if you set up to make a film about the person, especially a person who is known for his writing." Dziadosz said the filmmakers were thus challenged to find a way to "obliquely talk about his past and about him." They did reference his work, he said, "especially writings about animals — centered on the idea of looking at animals not as objects but as beings which are similar to us but very different." "In the second film which is the one about animals, [Berger] had made films about animals himself so we used some of that material," MacCabe said. They also recorded some unusual new footage. "There’s this thing up in the high Alps when they let the cows out after the winter where they’ve been locked up the whole winter when the cows kind of go mad," said MacCabe. "And it’s very rare to see it but they actually did capture some of that on camera." The Seasons in Quincy took a number of years to finish, which meant many seasons passed before it ultimately reached completion.

"The last film, which Tilda made, is about sons, or about children. She takes her children to see John in Paris and then they go to Quincy to meet Yves who is John Berger’s son, so it’s this kind of circle idea. It’s the rhythm of the Earth," Roth said. "Many babies were born [in the midst of making the documentary]. Bartek got a baby. Lily got two. But many mothers died as well, many people died and it’s that Berger-esque thing, because it took so long. It just took so long because it’s a process. People died. Babies were born. That takes time." Swinton appeared at the premiere for the film, and participated in a Q&A afterwards during which she read a letter from Berger which the author wrote for the occasion. Click here to watch that video. |

AuthorMatthew Carey is a documentary filmmaker and journalist. His work has appeared on Deadline.com, CNN, CNN.com, TheWrap.com, NBCNews.com and in Documentary magazine. |

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

Proudly powered by Weebly

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

RSS Feed

RSS Feed