|

Former prostitute who became an angel of mercy is subject of Longinotto's moving documentary

There are hard lives and then there is Brenda Myers-Powell's.

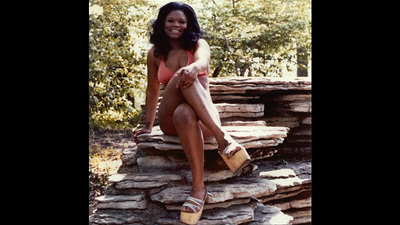

Before she turned one she had lost her mom. By age four or five she had been molested for the first time. As a teen she was forced into prostitution to earn her keep at her grandmother's place. For 25 years she lived a life that would have destroyed most people -- prostitution on the streets of Chicago, drug abuse, subjected to violence by johns and pimp -- her knees crushed in a baseball bat attack. It was kind of like love at first sight.

How can a person who endured so much brutality become a beacon of light and hope? That may be a mystery beyond solving, but the remarkable effect of her personal transformation can be seen in the new documentary Dreamcatcher.

British filmmaker Kim Longinotto directed the movie, which is now available on Showtime on Demand and oniTunes.

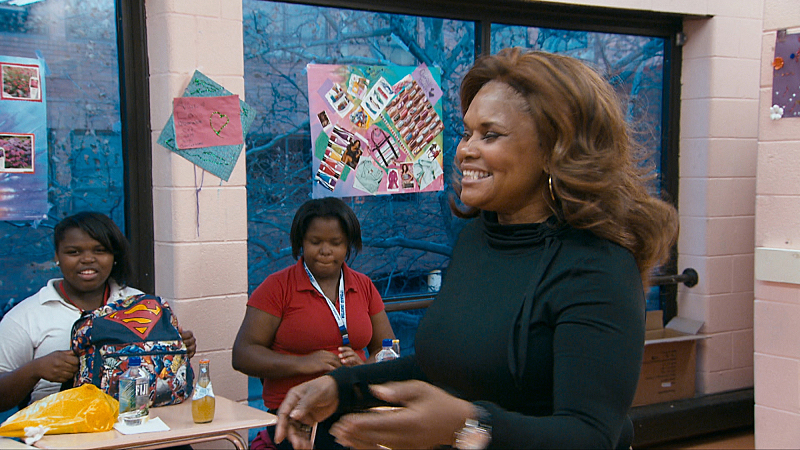

Under Longinotto's lens, Myers-Powell emerges as a compelling figure with an immense capacity for love. She counsels female prisoners serving time for prostitution and she established the Dreamcatcher Foundation to "end human trafficking in Chicago... [and] to prevent the sexual exploitation of at-risk youth."

Nonfictionfilm.com spoke with Longinotto in Los Angeles about her film and Brenda Myers-Powell. Nonfictionfilm.com: Brenda is the most extraordinary person. Kim Longinotto: I adore her. NFF: She just breaks through the screen. How did you meet her? Kim: I met her because Lisa Stevens, who’s the producer, knew her and she showed me a little trailer that she had filmed of Brenda. And it was kind of like love at first sight. It was like being at your first day at school and you think, “That’s the popular girl. I want to be friends with her!” It was kind of that immediate. I thought, I love this woman.

Kim: And what I love about Brenda -- and I love so many things about her -- is that she doesn’t pretend. She’s now "respectable," whatever that means — she’s got a house and a shiny car and a husband and a beautiful little boy and a job. Yet she says to the women [street prostitutes], “I’m you, I’m one of you.” She’s not saying, “I’ve come to save you.” She’s saying, “I’m you.”

NFF: She gave you such access to her life -- to those quiet moments when she's getting ready to face the day. Kim: I love that she took us into her world. So we see her in the bathroom with no makeup on, with no hair on. We see her looking for her hair [wigs]. We see that she puts this person together from scratch. One of my favorite scenes in the film is when she drops this persona that she puts together for work -- for being able to operate on the streets -- and she says, “Some days I can hardly hold it together. Some days, you know, I get panic attacks.” I know what pain is... If you want somebody that's going to care for you unconditionally, we're here to do that.

Kim: We kind of made the film together and that’s what the joy of it was. I learnt so much from her. I learnt that I mustn’t ever be ashamed of things that have happened to me. I’ve got to be proud of what’s happened and be a survivor. And being a survivor means you’ve got to say, “This happened to me,” if somebody asks you. And as she says at the high school, “It’s not your fault.” I mean, sometimes it is our fault, sometimes it isn’t. For little girls it’s not. And that we should actually own our own things that have happened to us in life. So I’ve learnt so many lessons from Brenda.

NFF: There are so many lessons that anyone can learn from Brenda. Kim: There bloody are, aren’t there! NFF: Her capacity for love is overwhelming. Kim: I know. NFF: She just reassures the women she counsels, and men for that matter, of a lack of judgment. Kim: It’s like Mandela, 27 years in prison and he comes out and he doesn’t want revenge.

NFF: Through the film we gain insight into the dynamics of victimization -- how many vulnerable girls are abused in childhood, tossed out of their homes, lured into prostitution and become drug addicted. And they're exploited by pimps who seem, at first, to offer love, and then only brutality. You include one of those former pimps in your film -- Homer.

Kim: I had a screening and these women went for me— “How come you’ve put a pimp in your film!” As if somehow we don’t [shouldn’t] treat them as human beings. NFF: I think it was wise to include him. The pimp is half the equation. Kim: Brenda teaches us that, doesn’t she. To me it was totally crucial. I wanted to know what Homer’s life was like. I wanted to know how a man could become an abuser. I was interested. He said, “My aunt and I had a love affair when I was nine.” And we all know that that’s not a love affair. It’s rape. It’s child abuse. And I remember thinking, “Ah, this makes sense.” He's actually a victim as well. NFF: Brenda talks about being a victimizer too when she was at the depths of her addiction -- helping to seal other girls into the life. Kim: What I think is so interesting about getting to know Brenda, and us trusting each other and actually loving each other and getting fonder of Homer, is that the boundaries between the victim and the victimizer is a fluid thing that shifts. There's a scene when Brenda tried to comfort Homer in the hotel room [when he was complaining about severe dental problems], which I find amazing. He was a man who with her pimp abused her terribly, tortured her for maybe 25 years, well a big part of that… And there she is saying, “Don’t worry. I’ll help you get teeth.” She’s saying, “Don’t worry Homer. We were all victimizers. We start off as victims and then…” You have to do things to survive that you’re not proud of. It’s not simple. Nothing’s simple in the film. Men and women isn’t simple. In the short space of 90 minutes with Dreamcatcher I think your perceptions of what people are keeps changing. And that’s what I look for in a film… The films that I really relate to are films where our perceptions of people change.

NFF: It's heartbreaking to hear the stories of high school girls that Brenda counsels. They talk about being raped and molested at a young age. As someone who comes from Britain, what does it make you think about the level of dysfunction in this country?

Kim: I think so many different things. One of the things that struck me about Chicago is we were staying very near where Obama [has a home, in Hyde Park]. And the thing that deeply hurt was that we were so close to an area where suddenly the street lights don’t work, suddenly the roads are all mashed up, suddenly it’s like a Third World street... And it was the segregation that hurt, and also the sense of abandonment of whole communities. We don’t have that in the same way in England. In London where I live it’s lovely. My neighbors on both sides are mixed race couples. It’s much more mixed — I’m not saying it’s perfect yet. We’re a much more mixed culture.

Kim: But I think my overwhelming feeling is that there’s things that are totally in common [between the US and Britain]. When they watch the film, I don’t want the audience to think, “This is America. That’s that there.” I want them to think that could be my mum or that could be my sister or that could be my daughter, that we’ve all got things in common — men and women and all of us. I know violence in the home is really, really common, like what Homer lived through. I mean my family was quite an unhappy family. It wasn’t as violent as that but there were all these things that we never spoke of, and secrets and lies and things you knew not to say.

NFF: You mentioned some viewers complaining about a pimp being included in the film. What other reactions have you received to Dreamcatcher? Kim: I’ve had women come and say, “I was abused as a child. I never told anyone. I’m going to actually tell you and this is the first.” We had a screening two weeks ago where people in the audience were standing up and telling each other things that had happened to them — whether it was their mothers that were being beaten up at home or whether it was women saying they wanted to leave bad marriages. And I had a kind of reaction a few weeks ago with this guy in the audience who said, ‘You should have talked about slavery.” And I thought, well no, I don’t want to talk about things. This is the women’s and girls’ and Homer’s film — it’s their film. It’s not a lesson. I’m not giving you a lesson and everyone will get something different out of it.

NFF: You really let the scenes play out. They’re very extended so it gives a particular pace to the film. That’s quite unusual for a film -- either narrative or documentary.

Kim: That’s like The Sopranos. I’m very inspired by fiction. I’m not actually inspired by documentaries that much. I watch a lot of fiction, a lot of series, and you see how scenes are put together and they’re usually three minutes long. You see how things play out, how in order for it to really hit home it has to have space round it and pauses. What I want is for you to feel like you’re there and you’re in this situation. NFF: In the film Brenda anguishes about having knee surgery, because she didn't want to be away from the women and girls she helps. How did the surgery go? Kim: It’s a long painful process back. I think one of her clients broke her knees with a baseball bat. I think that’s what it was. And also being dragged by a car along [the street once]. Everything was broken and mashed up and it’s all part of everything being destroyed on the street so she was pretty beat up in the street. And so it’s a long journey back, I think. |

AuthorMatthew Carey is a documentary filmmaker and journalist. His work has appeared on Deadline.com, CNN, CNN.com, TheWrap.com, NBCNews.com and in Documentary magazine. |

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

Proudly powered by Weebly

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

RSS Feed

RSS Feed