|

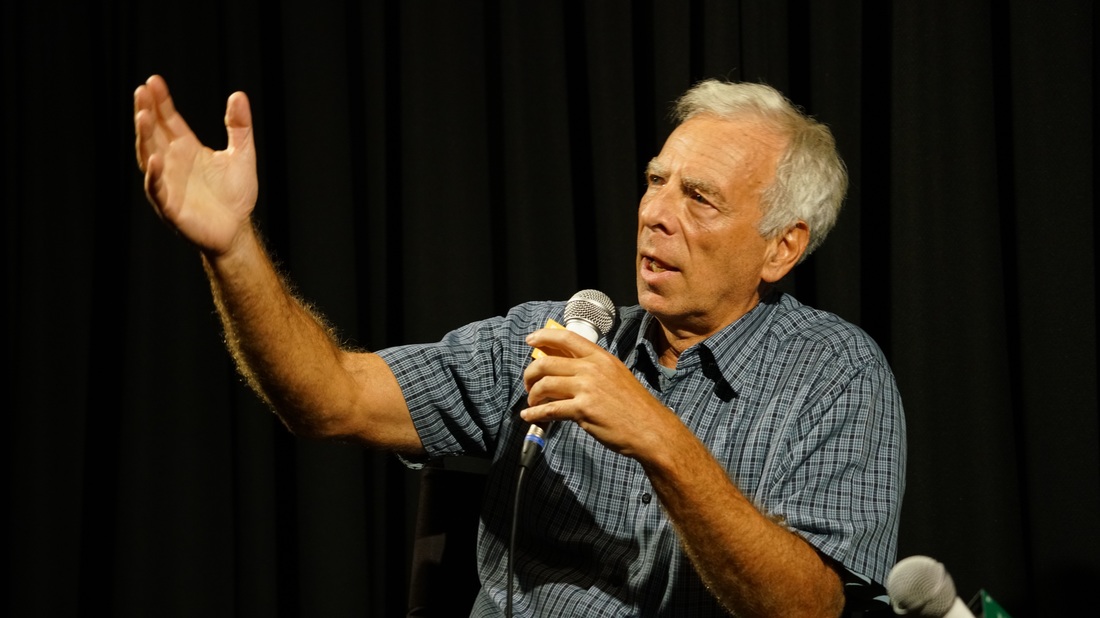

Marc Levin's film explores Manhattan neighborhood where gentrification transformed 'Wild West Side'

In the famous Kander and Ebb song "Cabaret" there's a couplet worth noting:

I used to have this girlfriend known as Elsie

For decades the Chelsea neighborhood of Manhattan was indeed known for its "sordid rooms," not to mention grimy streets and unprepossessing industrial buildings. A disused freight railroad track -- the High Line -- ran through it on an elevated course, abandoned to the weeds.

But in the past 10 years west Chelsea in particular has witnessed hyper-gentrification to the point where four sordid rooms could probably fetch a million dollars. A gussied up condo can easily go for $10-15 mil. Much of that development has been spurred by the transformation of the High Line from eyesore to a phenomenally popular park and urban sanctuary. Chelsea is suddenly the place to live. The neighborhood is in dramatic transition but all the different elements are still there in play. But how long that will remain is obviously a question.

Filmmaker Marc Levin has seen that transition firsthand.

"I have lived in that neighborhood for 40 years," he told Nonfictionfilm.com. "I guess you could call me an urban pioneer back in the day... I moved in with a bunch of buddies [to] a garment factory. There was no heat on the weekends. We were just young and crazy." The skyrocketing real estate prices are threatening to push everyone out but the super-wealthy. Levin may have to seek alternative digs for his Chelsea-based company, Blowback Productions. "I'm potentially one of the displaced in terms of my studio. There's no way once my lease is up in a few years that I'll ever be able to afford staying," he said. Levin's new documentary Class Divide speaks not only to what has taken place in Chelsea but to economic inequality in America generally that is widening the gulf between the haves and have nots. Class Divide just premiered on HBO. It will next air on Thursday (October 6) and is streaming on HBO Go and HBO Now.

SHARE THIS:

Levin focuses on a particular intersection in west Chelsea -- 10th Avenue and 26th Street -- that neatly encapsulates the neighborhood's new divide. On one side of the street is Avenues, the self-styled "world school," one of the city's newest and most elite private schools where yearly tuition runs 45k or so.

On the other side of the street is the Chelsea-Elliot public housing project, where family incomes average less than 30k a year. Only 115 steps separate the two places, as one enterprising Avenues student discovered when she paced it out. "I set out not to make an investigative piece but more to capture a moment, what I would call a sweet spot, where the neighborhood is in dramatic transition but all the different elements are still there in play," Levin said. "Capture that snapshot through the eyes of kids that come from such radically different places, that was the idea."

The film alternates between scenes at Avenues, where the students appear to be blessed with every advantage in life, and Chelsea-Elliot where young people face the expected challenges of life on the economic margins.

The Avenues students interviewed in the film are a remarkable group -- bright, inquisitive, sensitive and surprisingly aware of their privilege, partly because it's woven into the school's ethos to make sure the kids know how good they've got it. The Chelsea-Elliot kids interviewed in Class Divide are spirited, reflective and bursting with potential, like the sparkling Rosa, a dynamic 8-year-old who observes at one point, "Money was made by the Devil." "Rosa was a revelation," Levin declared. "She's just so full of life, street smart and smart. It was a joy. Not that her life doesn't have challenges, her folks struggling. But that was an inspiration just to connect with somebody like that." Another of the youngsters, the soulful Joel, lives with the anxiety that his father -- an undocumented immigrant -- may be deported. A family crisis comes when his dad, who has worked a menial restaurant job for a decade, is abruptly fired for making a sandwich incorrectly.

But there is pressure on the rich kids and the public housing kids alike, Levin says.

"I think there's an anxiety -- and you see it in the film -- that both sides share. The privileged kids know they're competing not just against Fieldston and Spence [private schools] but kids from all over the world and there's no guarantee that they're going to do as well as their folks do. And the kids from the low-income public housing -- the whole idea of public housing is like not even in our vocabulary. It's not even in the discussion. Our commitment to a social safety net, to kind of public investment, is at an all-time low. And so they're wondering, 'What's going to happen? Are they just going to sell this all? What's going to happen to my mom and my aunt and where I grew up?' And they see this change literally right in front of them, so there's no escaping it. It's like right there. And they have an anxiety about where they fit in." As a New York Times article put it last year, there are "longstanding fears that public housing buildings may ultimately be steamrollered by the hot real estate market — privatized or demolished to make room for richer New Yorkers."

Levin, who was born in New York, sees the city's very identity at stake.

"The magic of New York is the mix of humanity -- every type of person on this earth is somewhere in that city. And that energy is what has attracted people for years... So to lose that and for it to become a gilded cage or a gated community it would be a tragedy." Levin continued, "The irony is even the wealthy people or even the foreigners, what they're investing in is part of that magic. Forty percent of these [real estate] purchases are now LLC's, are overseas buyers, foreigners, Chinese money, Russian money, Israeli money. How do you control that?" Chelsea's hyper-development is symptomatic of a problem facing the country as a whole. As Levin puts it, "How do you make global consumer capitalism -- whatever you want to call this economic system -- how do you make it work better? And a fairer sharing of wealth. Not just out of some idealism but out of survival, that if the difference becomes so great that the kids at Avenues need to be picked up by bodyguards, need to be helicoptered in... Who wants that for their kids, whether you're wealthy, middle [class] or poor? It's an enormous challenge. "

One of the guiding principles of our society is that people like Rosa -- though hard work and persistence -- can rise above the economic circumstances they're born into. But Class Divide provides some sobering data about that.

"The statistic we throw up there is that class mobility -- which is the American dream -- is worse here than all these other countries -- Canada, Europe. It's harder here," Levin said. "That's staggering, staggering. That is the ultimate contradiction of what we all grew up believing -- in the American dream." Levin says he is heartened that at least the issue is getting some attention in this presidential election cycle. "What I think is amazing about what happened this year is that you have Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump both saying the system's rigged. In other words, that it's not working for the majority of Americans. And they've mainstreamed that idea and that's a starting point." What's critical is to see the wasted potential.

The outcome of the election will greatly impact tax policies that will affect whether the gap between rich and poor -- the privileged and the underprivileged, the Avenues side of the street and the Chelsea-Elliot side -- grows ever wider or narrows.

To Levin, expanding opportunity is in our collective self-interest. "What's critical is to see the wasted potential. If you look at it from just that kind of purely mercantile perspective of investing in something that you're going to get a return on and that's going to pay off instead of spending, two, three, four times as much to lock 'em up or to keep them in a ghetto or whatever," he said. The filmmaker pronounced himself optimistic, but not naive. "We as a society have been fighting these battles for [ages]. That's the story," he said. "I haven't given up hope." |

AuthorMatthew Carey is a documentary filmmaker and journalist. His work has appeared on Deadline.com, CNN, CNN.com, TheWrap.com, NBCNews.com and in Documentary magazine. |

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

Proudly powered by Weebly

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

RSS Feed

RSS Feed