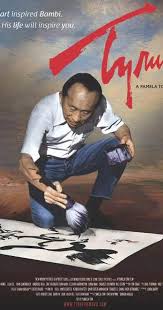

Director Pamela Tom on her Tyrus Wong doc: centenarian artist 'transforms ugliness into beauty'5/2/2016

Tyrus paints intimate portrait of legend behind Disney's Bambi who endured intense prejudice and 'tremendous loss'

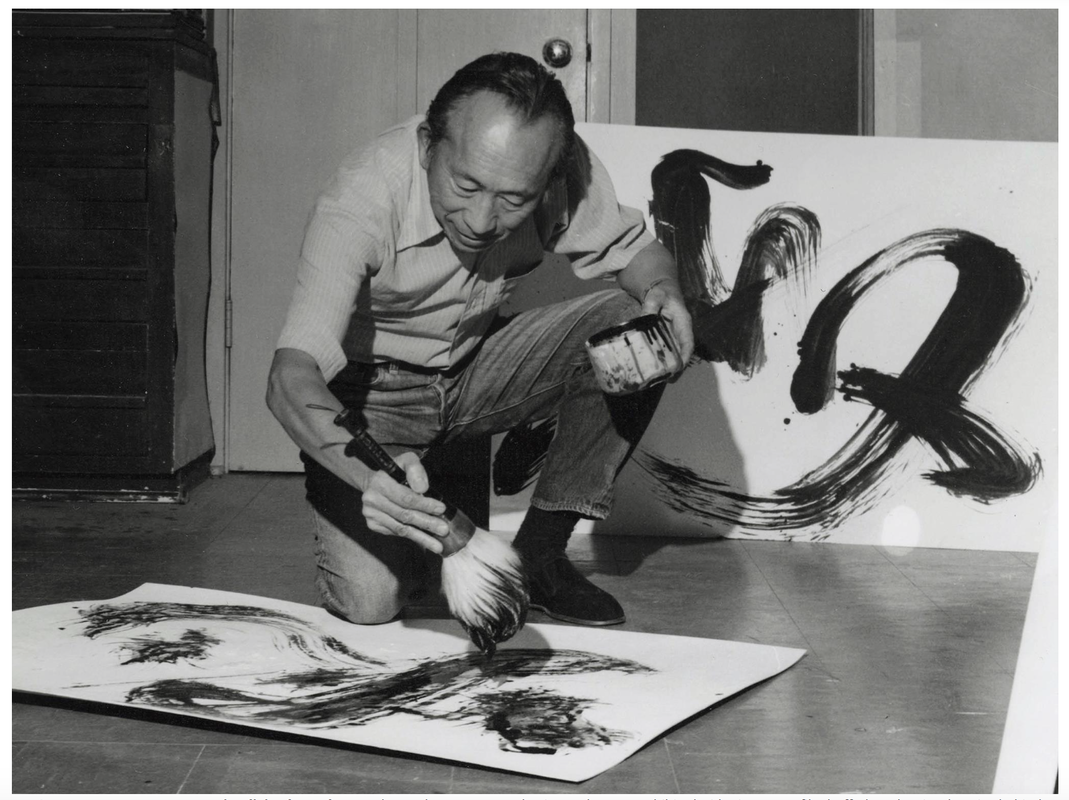

It took filmmaker Pamela Wong almost 20 years to realize her dream of completing a documentary about Chinese-American artist Tyrus Wong.

That such persistence and willpower were necessary seems somehow appropriate given that Wong himself faced exceedingly difficult obstacles in his quest to succeed as a painter. I think what his story tells is that he is a survivor...That’s what intrigued me too— how did he do it?

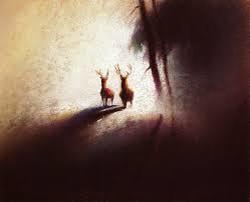

Wong, whose best known work is the conceptual art for Walt Disney's production of Bambi [1942], came to the U.S. at the age of nine, in 1919, at a time when Chinese immigration was officially banned under the Chinese Exclusion Act [enforced from the late 1800s until 1943].

He left behind a mother and sister he would never see again [the Chinese Exclusion Act made it almost impossible for families to reunite in the U.S.]

His first experience of America is [it] trying to push him back — you know, Angel Island [immigration detention center]. He was detained for a month and had to lie his way into the country. He came under an assumed identity... I don’t think people today fully recognize or can fathom how difficult it was for the Chinese-Americans and other immigrants during that period.

Tom's documentary Tyrus played at the Los Angeles Asian Pacific Film Festival last week, after previous screenings at the Telluride Film Festival and its premiere at the San Diego Asian Film Festival.

Remarkably, Wong attended the LAAPFF screening, along with his three daughters. At age 105 he is said to still enjoy flying kites of his own making along the beach in Santa Monica, California.

Nonfictionfilm.com spoke with Tom on the eve of the screening of Tyrus at LAAPFF. She told NFF the documentary came about after she heard about Wong's work and set up a meeting with him in Los Angeles.

Pamela Tom: I invited him to have lunch at my brother’s Chinese restaurant downtown and it was like a three hour lunch and during the course of that time I discovered that not only had he worked on Bambi but that he had worked at Warner Bros. for 26 years and was a painter, built kites, all these things. And I said, “Oh, yeah, I’m making a movie about you. I don’t have any money but I’m making a movie about you right now.” So that’s how it started. NFF: This is a remarkable personal story but it’s embedded in the American experience. What does his experience tell us about what life was like for Chinese-Americans at that time -- the 20's, 30's, 40's? PT: I tell people -- because they think it’s a documentary just about his art -- really it’s a film about the Chinese-American experience in the 20th century. And the two are inextricably entwined. He came over as a nine year old in 1919 and his first experience of America is [it] trying to push him back — you know, Angel Island. He was detained for a month and had to lie his way into the country. He came under an assumed identity. I don’t think people today fully recognize or can fathom how difficult it was for the Chinese-Americans and other immigrants during that period -- let alone to travel down the path as an artist and in Hollywood. We talk so much today about diversity and how difficult it is [in Hollywood] -- the obstacles and the lack of diversity. It’s like, okay, go look at Tyrus’ story back in the 30's and now we’re talking real difficulty.

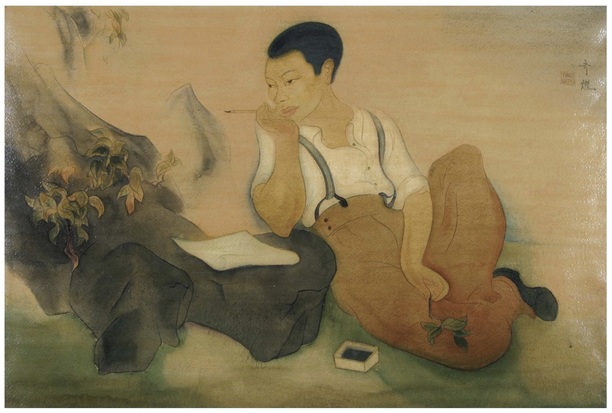

PT: I think what his story tells is that he is a survivor. He was resilient and he somehow was able to navigate these worlds that had so many barriers. That’s what intrigued me too— how did he do it? What was it that was in his character that allowed him to do that and not be bitter, not give up, not just say, “screw it all” and go open a restaurant. But it’s because he had to be an artist. He had no other options. That was the only thing he loved to do; that was the only thing he was good at. It’s like it’s fate.

I think about what would have happened had he stayed in China during the Cultural Revolution. I think still he would have been an artist somehow. He probably would have been in prison. But he still would have become an artist.

NFF: He has lived an extraordinarily long life now. How do you describe him?

PT: Tyrus has an artist’s eye. He looks at things and he transforms ugliness into beauty and I think this is what has sustained him through loss — tremendous loss. He lost his wife, he lost his father, never saw his mother again [after he left China]. How do you survive that in a country that is so hostile to you? And I think it was just his art. He’s just always seeing things. When I’m with him he’ll say, “Oh, that chair has a lot of character.” I’m like, “Oh, yeah, that chair does have character, you’re right.” And his humor. He’s really funny. I’m like, “How did you do this? How are you not bitter?” He says in the film, “It’s not good for my health to dwell on that. It’s just not good for my health.” He just doesn’t want it. He was really reluctant to talk about the racism [he experienced] but most journalists — and myself included — want to know those stories, right. That’s where the conflict is. It’s almost like I felt it was a disservice [to him], like “Come on, go back there, get angry, tell us the story.” And I think in his later years he felt liberated to tell them because back then you had to kind of keep it down. You had to kind of suppress a lot of that. And I think now he’s feeling like, “Okay, I’ve gotten it out and I’ve made peace with that.” But when you get him on a roll he can, it just all comes out. I think back then you couldn’t afford to let it out.

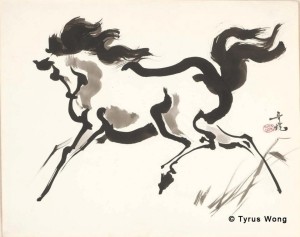

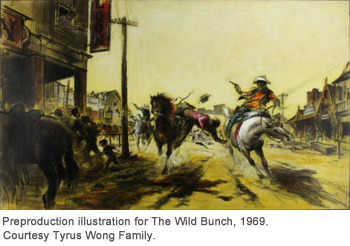

NFF: How did his work on Bambi come about?

PT: He graduated from art school in the middle of the Depression, like 1932, very hard to find a job. So he was kind of freelancing, scraping by and then he met a woman — Ruth. Fell in love, got married, had a baby and decided, “I need to get a job.” So his wife said, “You know Disney hires artists.” So he went over and brought some of his paintings and got a job as a lowly “in betweener” — entry level, tedious, mind-numbing job. Not something that a trained, exceptional artist would love. But anyway he did that and then found out Bambi was in pre-production. They were still looking for the look of the film so he went home, read the book — it speaks to his resourcefulness — and painted some landscape pictures with the deer in the forest and brought them to work and showed them to the art director — a guy named Tom Codrick. Tom looked at them and brought them to Walt Disney. Walt saw them and said, “This is the look. This is it. This is it.” So Tyrus keyed the whole look of the film. He was not an animator and he wasn’t even a background artist per se. He would get the script and it said, “Forest fire,” whatever. He would paint, what would a forest fire feel like? What would it look like? The tone of that. And then like the snow scene — what would that look like? So he would just do hundreds of these sketches and then everybody would just sort of follow that look. So he was really the visual stylist, the production designer you would maybe call him today.

NFF: It was quite a lengthy process to complete the documentary. What were some of the challenges you had to overcome?

PT: It was a very long process because it was independently produced... I was writing so many grants. So it was fundraisers, putting my own money into it, and begging, borrowing, whatever I had to do, [meanwhile] having a family and working a full time job. So that’s partly why it took so long. But really what I think got easier is when Tyrus’ star started rising again. There’s more national recognition [than when I started on the film], there have been books written about him, the Walt Disney Family Museum did a retrospective of his work, a lot of the Disney animation people were writing about him. So I think as people started recognizing, “Oh, this is an artist of note and whose story is important to tell,” it was like, “Oh, yeah, we’ll give you money.” But back then [when I started] it was kind of the dark ages. I recognized his story. I was passionate about it, so were a bunch of Disney animation fans, so was the Chinese-American community. But that alone was not enough to fund a feature-length film at the quality I wanted to make this, you know what I mean? I wanted to make this befitting an artist. |

AuthorMatthew Carey is a documentary filmmaker and journalist. His work has appeared on Deadline.com, CNN, CNN.com, TheWrap.com, NBCNews.com and in Documentary magazine. |

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

Proudly powered by Weebly

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

RSS Feed

RSS Feed