|

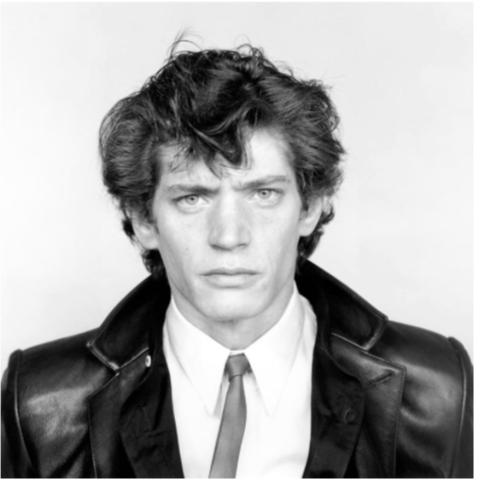

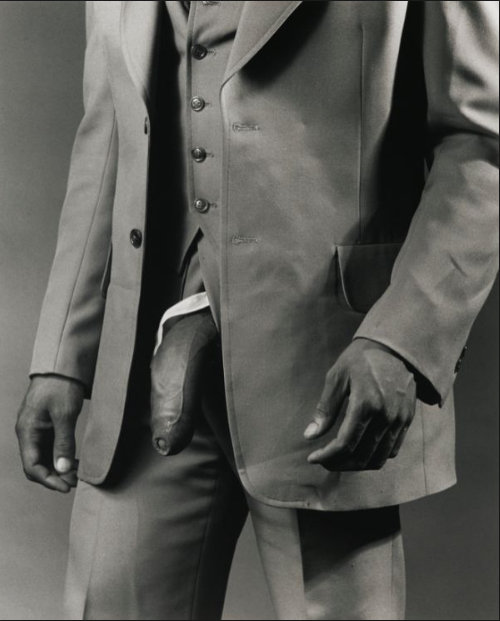

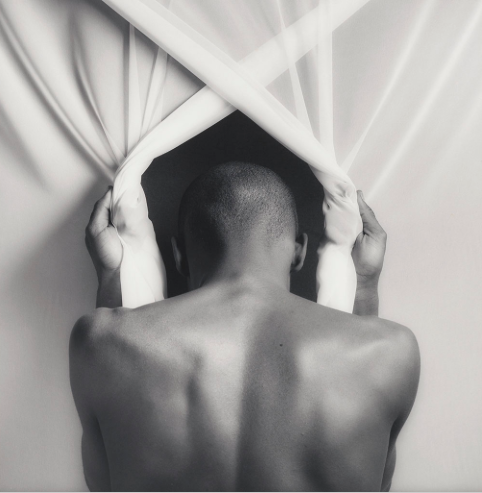

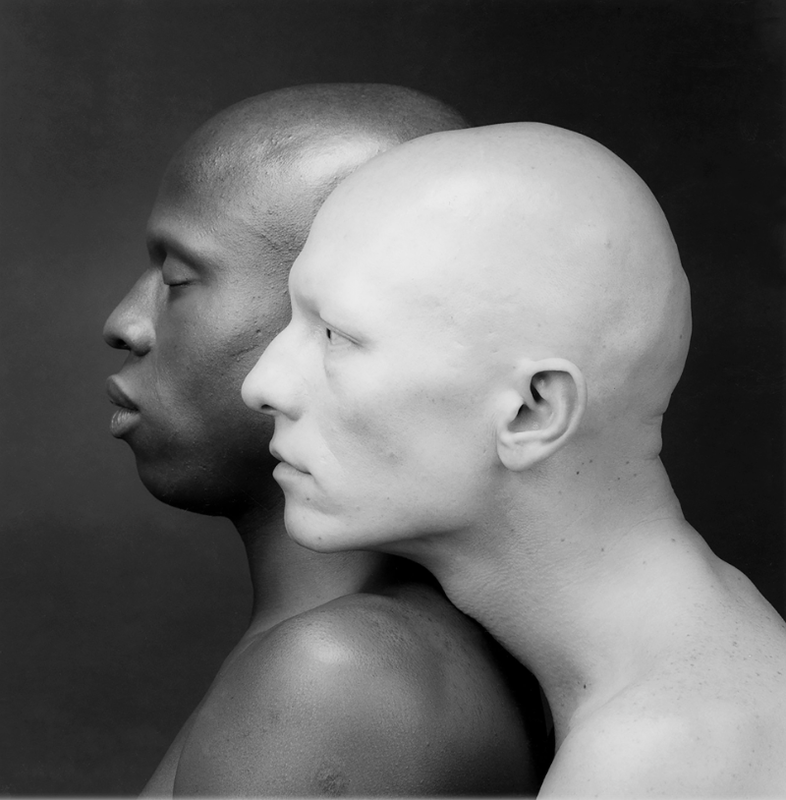

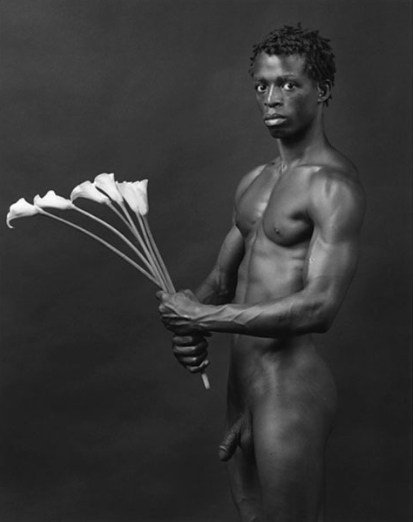

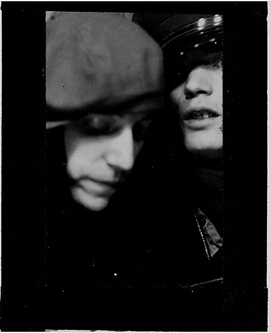

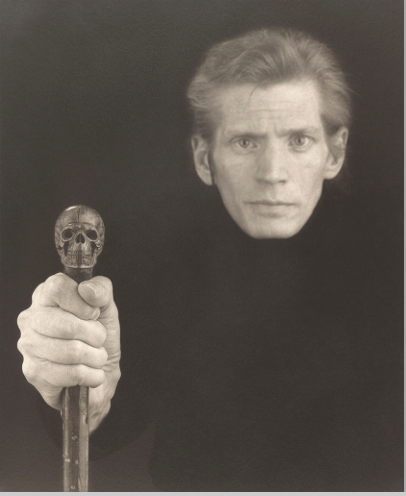

The filmmaking pair bring Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures to theaters and HBO Fenton Bailey and Randy Barbato's new documentary Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures is hardly hagiographic. "I’ve had conversations with people who’ve seen the film and they’ll be like, 'He’s such a jerk,'" Barbato told Nonfictionfilm.com. He quickly added that he and his co-director don't view the late photographer that way. "We started this film knowing that we liked a lot of his work but having kind of ambivalent feelings about him, like thinking, “I don’t know if I like him," Barbato told NFF at the Berlin Film Festival, where their documentary celebrated its European premiere. ”I ended up really liking him. And I think that shocks some people." People said [Mapplethorpe] couldn’t talk about his work and that he wasn’t very articulate. And we found the complete opposite to be true. He was incredibly articulate and incredibly open and honest and direct. Mapplethorpe shocked a lot of people during his lifetime [1946-1989], but mostly for the subject matter of his photography: homoerotic images, sadomasochistic gay sex, fetishism. Even flowers, under his lens, revealed an erotic potential. There were portraits too -- great ones -- but his celebratory depiction of male sexual organs and sex acts are what most defined him. The full range of Mapplethorpe's work is on display in Bailey and Barbato's film, including his X Portfolio, the collection of intensely graphic gay BDSM images; in the film some rather uptight-looking museum curators handle the linen portfolio as if it were a medieval illuminated manuscript. "Mapplethorpe was all about putting it all out there without shame, without apology which was ahead of its time then and I still think even today we find it a little bit -- we’re taken aback," Bailey said. "I think for many people it’s still very uncomfortable-making to see graphic imagery in a public setting, whether it’s a museum or a theater," Barbato added. "People still have a kind of puritanical reaction." People in LA and New York are getting a chance to see the film on the big screen, and it debuts on HBO April 4. Concurrently, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art [LACMA] and the Getty Museum in West Los Angeles are putting on shows dedicated to Mapplethorpe's work. Mapplethorpe was unorthodox for his time not only in his subject matter but for the way he pursued his career, Barbato and Bailey said. "I do think that part of his significance is that he was one of the first artists who kind of fused the idea of artistry and commercial success and made it okay to be sort of ambitious about wanting to be a successful artist," Barbato told NFF. "His ambition was naked and he was open and honest about it. I think particularly in that time, in the 70s and 80s, I don’t think that was a particularly acceptable thing to do or a way to behave. I found that really admirable." Barbato said Mapplethorpe tended to associate himself with those he thought could advance his career. "It seems like he was on a mission to connect with people who in one way or another would kind of propel his narrative… He connected with people who were storytellers, who were writers," he said. "And he always wanted them to write about him," added Bailey. "And talk about him," said Barbato. Several of his friends and photographic subjects spoke to the filmmakers, including writer Fran Leibowitz, Debbie Harry of "Blondie," designer Carolina Herrera, writer Bob Colacello and actress Brooke Shields. But Mapplethorpe's close friend and one-time muse, Patti Smith, who wrote a memoir of their time together, Just Kids, did not consent to an interview. "We love that book [Just Kids] but we wanted to tell his story and we really wanted no shadows to be cast over it. We actually started with the pictures and then with every bit of audiotape of him that we could find," Barbato said. "I think the film is complete. She’s in this film to the extent that I think is appropriate." "Yeah, to the extent that she was in his life," Bailey added. "Just Kids is just a chapter. And this film is the whole story and it’s his story told by him as opposed to someone else... The main voice in the film is his own voice. There’s 15 minutes of him talking. He’s the most important interview in the film." If Robert Mapplethorpe is the most important interview in the film, surely the second most important is Edward Mapplethorpe, the artist's younger brother [13 years younger]. Edward served his brother for years, working with him in his studio, printing his work. "Edward is kind of the heart of this film and appropriately so. He also is a pretty great artist who I do think had a very serious collaboration and significant impact on Robert’s work and success," Barbato said. "On top of that he helps us make that kind of connection that humanizes Robert in a way that I think only Edward — and Nancy, his sister to a certain extent — but really only Edward could do." Humanize perhaps — in the sense that an artist's narcissism renders him "human." Robert Mapplethorpe, as depicted in the film, happily relied on his younger brother's help — so long as Edward never attempted to overshadow him. If Robert owed a debt to Edward, it's one he never repaid. "There’s a lot of pain associated with Robert’s passing," Edward told Nonfictionfilm.com in Berlin. "There’s some pain involved with the fact that Robert didn’t support my own career and my own vision and even to his dying day, which I was really thinking and hoping and praying and expecting in some respects and didn’t get. But now this is 2016, Robert died in 1989 and it’s part of my reality, it’s part of my person." "From the moment I started working with him I felt very protective and I felt very dedicated, wanting to respect him as a person, as an artist," Edward said. "I could have easily have [become] like bitter and angry and talked badly but he’s my brother and he’s a part of me. I want his spirit to live." "Edward brought so much technical aspect to [their collaboration] because he was the one with the formal photographic education. He brought a lot to the table," Katharina Otto-Bernstein, who produced the documentary, said. Addressing Edward directly, she noted, "He relied on you. That picture ultimately was your composition." "That picture" she's referring to is one of the last images of Robert Mapplethorpe, holding a skull cane, taken months before he died of complications from HIV/AIDS. "It was an idea that just occurred to me after him expressing that he wanted to photograph the skull cane, which was a beautiful object in itself," Edward recalled. "It was given to him by a close friend.. It [the photograph] was just a concept, like 'this is too big of an opportunity or too important of an opportunity to pass up.' I asked Brian [English], who was the other assistant, to do that Polaroid and the two of us, our eyes just got very wide… It wasn’t easy [to get Robert to sit for the photo] because he really wasn’t felling well. But I said, 'Let’s do this because I think this is something that you need to do.' So he put on a turtleneck. We had the black background…" Asked about technical aspects of the photo, Edward added, "It’s probably f-22 or something like that but because we’re so close the depth of field is somewhat shallow. I mean we wanted his face to be somewhat in the background and not sharp. So it was just a matter of finding the right combination of light and f-stops to make it sort of ghostly in a way." The documentary includes archival footage of Sen. Jesse Helms who thundered against Mapplethorpe after the artist died, accusing him of "promoting homosexuality." The subtitle of the film, "Look at the Pictures," is taken from the exhortation Helms delivered to his Senate colleagues, a speech in which he ripped up one of the artist's graphic photos. That incident came in the midst of a bitter debate in the late 1980s over public funding for the arts.

"Man in the Polyester Suit was the one he 'Helms] tore up,." Bailey said. "That was the one he made such a histrionic display about... which I suspect is what Mapplethorpe would have intended or would have wanted. I think he was quite happy that he could use the political process and political outrage to secure his place as a very famous artist." Mapplethorpe's acclaim has only grown in the years since his death. Does his work still have the capacity to shock, more than 25 years after the artist's passing? "It’s a really good question and one that only the film playing will sort of answer," Bailey said. "I don’t know how people still feel about it. At the screening [in Berlin] it did feel still transgressive. To see them [the photos] on a huge screen with a whole group of people and in the context of art still felt -- I felt I could hear people gasping as you go through the X Portfolio... I was still a bit shocked partly because the screen is so big. And I could sense the tension in the room. So it’s still transgressive." |

AuthorMatthew Carey is a documentary filmmaker and journalist. His work has appeared on Deadline.com, CNN, CNN.com, TheWrap.com, NBCNews.com and in Documentary magazine. |

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

Proudly powered by Weebly

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

RSS Feed

RSS Feed