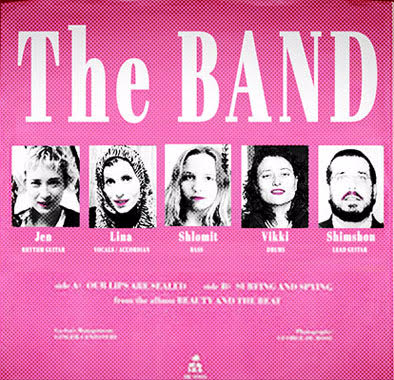

Docs in progress: 'The Promised Band' -- fresh, nuanced look at Israeli-Palestinian divide12/28/2015 Documentary by Jen Heck tests whether cross-cultural friendship is possible in a land of intractable conflict To many people "Middle East Peace" is an oxymoron -- so farfetched is the idea of Israelis and Palestinians finding common ground. But Jen Heck hasn't abandoned all hope. The American filmmaker spent months in Israel and the West Bank exploring whether a group of Palestinians and Israelis could literally see eye-to-eye. Could they spend time together, face-to-face, no barbed wire between them. What would it take to just hang out? I see this guy crossing the street with a machine gun and I’m like, 'Oh, this doesn’t look really good.' The answer, as it turned out, was to form a band, a process Heck documents in her new film, The Promised Band, which is about to launch on the festival circuit. Heck and producer Maria De La O gave Nonfictionfilm.com an exclusive first look at the documentary before festival programmers screened it. We found it moving and surprisingly tender, a film that makes the dynamics of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict so much more human and comprehensible than news reports or other documentaries that focus just on the region's incessant violence. The origins of the film go back to Heck's work on a previous project in which she filmed the first all-Palestinian expedition to Mt. Everest. A Palestinian teacher, Lina Qadri, was to take part in that climb, but couldn't secure permission to leave the West Bank. Heck later traveled to Israel and the West Bank and visited Qadri at her home in Nablus -- a place officially off limits to Israelis. The two quickly got close. "Lina and I became fast friends and I already had friends in Israel, so I found myself visiting both places a lot over those first few months," Heck says in voiceover in the film. "I came to know and love people on each side of the border [but] crossing the border between Israel and Palestine raises eyebrows on both sides." Nonfictionfilm.com spoke with Heck and De La O about The Promised Band, and the challenge of making a movie in such a fractious part of the world. NFF: This is your first feature-length documentary? Jen Heck: This is my first feature-length documentary. NFF: So for your first full-length doc you thought you’d take take on a nice light subject like Middle East peace. Jen: My personal relationships brought me closer to this subject matter and that’s sort of how it happened — snuck up on me. I wanted to bring different friends together. And my Israeli friends in particular kept begging me to go on these trips to the West Bank with me [to see Lina] and they would always cancel at the last minute. And then you start to realize there’s this curiosity and this intention and then it's totally curbed by this intense fear that people have. I had been crossing the border [between Israel and the West Bank] so I didn’t have the same feeling. I didn’t live there so I didn’t watch the news and hear the same sort of — I would say “fear tactics” but some of it’s not... People are afraid — I saw that inner conflict in a lot of people. I like listening to people and I really just ended up getting a lot of information and really personal stories... People wanted to talk to me because I’m sort of neutral — I’m not religious in any particular way, like Muslim, Christian or Jewish. Technically I’m Catholic, I guess. People wanted to convince me of their side of the story. I was in a unique position to address it [the social-political divide], I guess. NFF: Maria, how did you become involved in the project? Maria De La O: Oh gosh. I’ve known Jen for a very long time. I was her first boss. We worked on the same website and then we lost touch. And then we ran into each other at a film festival maybe 10 years ago and then we just started playing around with different projects. She called and said, “Hey, you want to go to Everest?” and I said “Well, yeah. When?” Then [later] she was like, “Hey, want to do a documentary on Israel and Palestine?” I said no. [laughs]. She got mad at me. “What about that Everest thing we were doing?” Everest was totally easy [in comparison]. NFF: Why did you say no to the Middle East idea, at least initially? Maria: It just seemed— I can see both sides of the issue and it just seems so intractable. And I was like, “Well, why would you want to get into a quagmire like that for your first feature?” [laughs] There’s so many easier stories, you know. I think that’s why we tried to keep the film personal. Of course it’s about politics, yes, but it’s really about these people. This is one of the most precarious places in the world. Sometimes you're not sure who you can trust. And using friendship as a reason to cross these borders just provokes suspicion. Maria: It was risky for us because we were like, “Do people even care about this subject? And we have no authority to be talking about it at this point.” I think that we didn’t try to hide our naïveté in the way the documentary is presented, the way that Jen is presented in the movie. I think that could be something that people blast us on so I think we tried to turn it around and make it a strength. NFF: You eventually encountered a couple of Israeli women -- Shlomit Ravid and Viki Auslender -- who were both curious and brave enough to make the illegal journey into Nablus to meet Lina. It's something seemingly so simple — friends getting together who enjoy each other’s company — but almost impossible in those circumstances. Jen: Yeah, yeah. NFF: And it’s so telling, of course, about the politics and the conflict of that part of the world. The film suggests Israeli and Palestinian authorities have a vested interest in keeping their peoples, in effect, segregated. Jen: Like all we [want] to do is get in one room... This is something people do everyday everywhere that we take for granted and just showing how hard it is to do something so simple — the politics, it sort of self-explains... When you see people trying to do something so innocent and like the weirdness that comes from that — you’ve got the borders and the laws but you’ve also got social pressure, in some cases unspoken, or it comes out as an awkward comment from somebody’s relative or whatever but that social pressure [against Israelis and Palestinians spending time together] is like really powerful. I've never talked to a Palestinian before... This is just something that people don't do. NFF: So this is why you came up with the idea of forming a band, with Lina, Jen, Shlomit, Viki and other friends -- as an excuse to explain why you all were hanging out. You all had at least some musical ability, so it made some sense. Jen: It was very awkward for everybody to be crossing these borders. It was awkward for Lina to have us there [in Nablus]. Her neighbors would look at her funny. She could possibly have political pressure because it’s a very close-knit community. The same for Shlomit. It’s like her family was, “What are you doing?” The band thing really became kind of like a mechanism to have a way to talk about what we were doing without making it feel so threatening to people. Because if you were like, “I have a friend in Nablus,” people would think you were crazy or you were a terrorist. But if you’re like, “I’m working on a film,” or “I’m working on this cultural project with this American,” [or "We're in a band"] people would be like, “Okay, I guess that could make sense.” It was nerve-wracking but still possible at that time to do that and so we just did it.. All of this stuff, by the way, I would never do now. Going back and looking at it, it’s like we just kind of went with it. They thought we were spies. If you have a camera they think you’re a spy. NFF: Was it scary to be shooting video in the West Bank and in Israel, for fear of attracting attention with the camera? Jen: [In Nablus] we were in a lot of small spaces. And like if I went to look in a doorway people would be like, “Don’t look in that doorway.” And another time we actually almost got arrested. And that was really scary... I was trying to get a shot that was like a graphic match of something I’d shot in Israel and it was inconveniently located across the street from a Palestinian prison in Nablus. Lina [was] in the car. We had Shlomit in the car illegally, completely illegally [because as an Israeli she wasn't permitted to be in that part of the West Bank]. And I look over and I see this guy crossing the street with a machine gun and I’m like, “oh, this doesn’t look really good.” And so he comes over to the car and he said, “I need you guys to pull over...” I thought for sure I was going to have to go to jail but somehow Lina [got] us out of it. They [Palestinian authorities] thought we were spies. If you have a camera they think you’re a spy. When they finally let us go we had to drive around for a while and make sure we weren’t being followed. It was kind of crazy. That kind of thing was always hovering over us. NFF: What did you do in terms of financing the film?

Maria: We kind of just did it as we went along. For the first few trips it was basically self-financed, me and Jen... Then we did credit cards and our own money and then once we sort of got together enough footage I showed it to someone in San Francisco named Ian Reinhard and he’s executive-produced quite a few films at this point. The last one was Batkid Begins... He looked at our footage and he was excited. And so at that point he kept us afloat. He’s given us a lot of funding for editing and basically everything after principal photography. Jen: He’s an angel investor for us... I mean, he’s carried a lot of the weight. NFF: What are the release plans for The Promised Band? Maria: We just started submitting to film festivals. We probably submitted to a handful at this point. We’ll see what happens. And of course we want distribution. We’re just kind of at the beginning of that stage. NFF: How concerned are you about possible consequences for the people who took part in the film? Once the film comes out and is seen do you think there may be repercussions for them -- Lina, Viki, Shlomit, Noa and others in the band? Jen: That’s always been a concern. It depends on when the movie comes out and what’s happening [in the Middle East]. It’s very hard to say, but there will be repercussions. Will it be like people have to go to jail or something? My Israeli friends told me they don’t think that would happen. Like they would be reprimanded. A lot of us felt like more of the hardship would be on Lina, but I don’t know. I just don’t know. It’s actually hard to get people to fully speculate on that... I definitely think the Israelis are going to get a really hard time from their community. Lina, since we finished the film, she’s gotten divorced and she’s really established herself as an artist. She’s sort of just a free spirit sort of person and she embraces that completely so I don’t know if anyone today would be surprised by anything she does in the film. I don’t know. Maria: [Lina's] moved to Ramallah, which is where all of the U.N., the non-profits, all the international organizations are based so it’s definitely known as a much more cosmopolitan city than Nablus. That probably gives her a measure of safety. NFF: Do you have hopes for what the impact of the film will be — either on an individual or perhaps larger level — once people do have a chance to see it? Jen: I think it will change the world, to be honest. Just kidding. It’s a weird movie. Movies about a bunch of ladies — I always worry that if something isn’t blowing up people aren’t going to want to see the movie. But it has its moments of nuance. Everyone I’ve shown the movie to or stages of the movie to — particularly in the region on both sides of the fence there — people really respond to it in a positive way, Palestinian or Israeli. I think religious people are going to have a problem with it, regardless of what side they’re on. And I think we’re going to get some push back from that. So when you talk about the overall reaction to the characters, part of that is dependent on where religious people stand in their cultural landscape… I think those groups are going to be more angry but I hope that people can respond to the personal nature of it and relate to it and that it opens up the issue to people. We have to ride this line between making it easy to understand for American audiences — because obviously the politics are complex — but still keeping it fresh enough and not all about explaining politics for the regional audience… So hopefully we hit that balance so we can reach the widest audience possible. |

AuthorMatthew Carey is a documentary filmmaker and journalist. His work has appeared on Deadline.com, CNN, CNN.com, TheWrap.com, NBCNews.com and in Documentary magazine. |

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

Proudly powered by Weebly

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

RSS Feed

RSS Feed