|

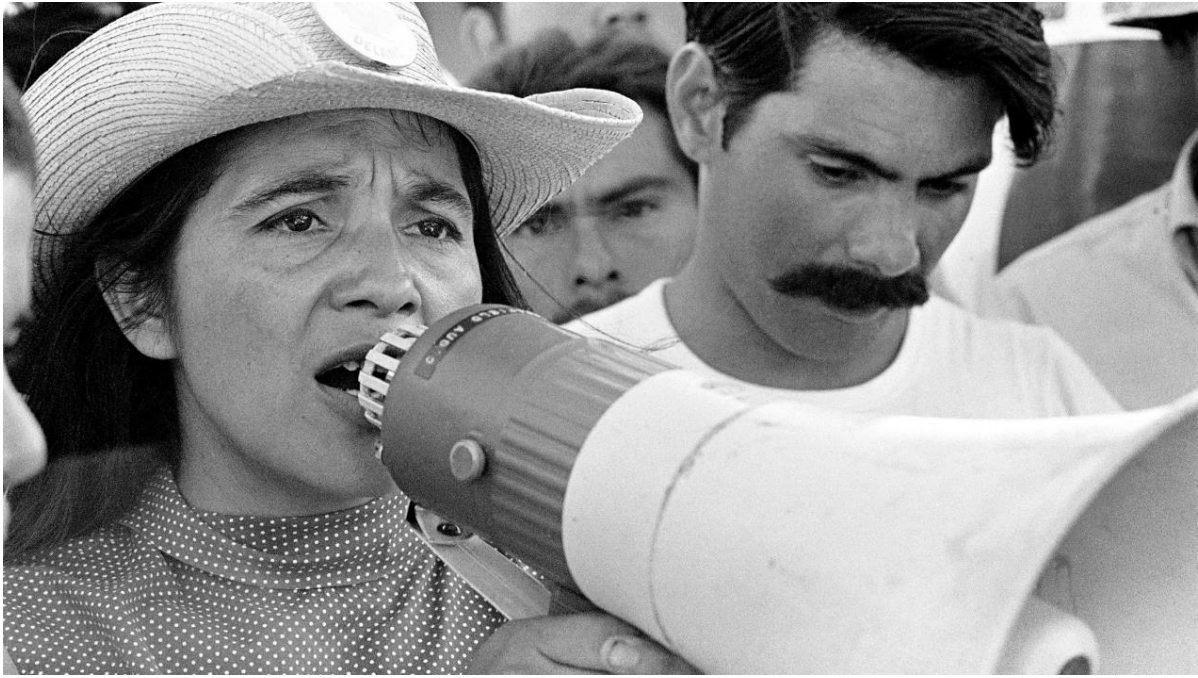

Peter Bratt's documentary Dolores expands to L.A., SF Bay area this weekend

Update 9/22: Dolores expands to more cities today including Chicago, DC, Philly [click for details]

Director Peter Bratt grew up in the Mission Dolores section of San Francisco, so perhaps it's appropriate that his latest film revolves around a Dolores on a mission.

The Dolores in this case is Dolores Huerta, the community organizer, labor activist and co-founder of the United Farm Workers union. At age 87 she is only now receiving wider recognition for a lifetime of work on behalf of some of society's most vulnerable people -- a correction of the historical record due in large part to Pratt's film about her, titled simply Dolores. Dolores challenges the three pillars and foundations of the culture which is capitalism, patriarchy and white supremacy.

After opening last week in New York, Dolores expanded Friday to Los Angeles (Nuart Theatre), San Francisco (Opera Plaza), Berkeley, California (Shattuck Cinemas) and San Rafael, California (Smith Rafael Film Center). It opens in additional cities in the coming days and weeks. Full details here.

Huerta and Pratt will be making several appearances in conjunction with screenings this weekend, in L.A., San Francisco and Berkeley. Details here.

Huerta was born in 1930 in New Mexico -- a fifth-generation American, as she points out. That's not simply an expression of pride in her heritage; some of her Anglo antagonists assume her to be an immigrant.

"As I say in the film, my great-grandfather fought in the Civil War. My dad was in the military, my brothers were in the service also," she told Nonfictionfilm.com during a conversation Thursday in Los Angeles. "My dad was an Assemblyman in the state of New Mexico. And yet people look at me and go, 'Do you speak English? Go back where you came from!'" The documentary traces her roots as a community organizer, under the tutelage of Fred Ross. It was Ross, a labor activist, who would introduce Huerta to Cesar Chavez in the 1950s, creating a tandem that would eventually organize farm workers against ferocious opposition from growers, and their allies in law enforcement and political office, including -- in the 1960s and 70s -- Gov. Ronald Reagan in California. A good organizer is a social arsonist who goes around setting people on fire.

Huerta's social conscience manifested early, as she worked to address economic injustice as a young woman in Stockton, California, where she moved with her mother after her parents' divorce.

"I was raised by a single mother and the way that she taught us was to always try to do the right thing and also we have an obligation to help people," Huerta explained. "And if there's any way you can lend a helping hand to someone that's in need -- even if they don't ask you for help -- you're supposed to be able to get out there to help them. And not expect gratification and not to expect any recognition." She added, "My mother was a great devotee of St. Francis of Assisi. And St. Francis Xavier. I was raised in New Mexico and everybody had a statue of St. Francis in their home and I think that was kind of the influence. My mother was a businesswoman but she was very committed to the community and helped many, many people."

Bratt, himself the son of a human rights activist, expressed admiration for the woman whose story he told.

"That's the remarkable thing for me as a filmmaker, especially when you're combing through just years and years of archival footage and you're hearing and seeing Dolores in her 20s and Dolores in her 30s and her 40s and speaking with such moral authority and clarity. And then to see her, now 87, still speaking with that same clarity and moral authority, it's astounding." He admitted to having concerns when he embarked on the project that Huerta would live up to the legend that surrounds her. "I did have some apprehension, like 'Oh god, I hope I'm not disappointed.' But she's still working. She started off as a community organizer at the grass roots level and she still a community organizer at the grass roots level with that same authority and clarity and it's really remarkable, truly."

The film documents the long odds Huerta and Chavez faced as they tried to organize farm workers in California to achieve collective bargaining rights.

"The farm workers were the most discriminated and abused people to the point that they didn't have toilets in the fields for the farm workers. That is how denigrated they were," Huerta observed. Strike actions were effective to some degree, but the farm workers movement did not prevail until Huerta, Chavez and their compatriots organized a boycott, which became one of the most successful campaigns of its type in American history. "We had this incredible movement of people not eating lettuce or grapes and not drinking Gallo wine, which brought the growers to the bargaining table," Huerta recalled.

Despite her critical role in the union, Huerta's contributions have been systematically underplayed, with almost all of the credit for the movement's triumphs going to Cesar Chavez. Huerta remains reluctant to take credit for the union's accomplishments.

"Cesar was the spokesperson for the union and of course he was a genius, a man who never went to high school, only went to the 8th grade, doing these incredible fasts that he did, going for 25 days twice without eating to bring the attention of the world about the situation of farm workers, the condition of farm workers," Huerta said. It's good that we march. We have to march, but we've also got to go to the ballot box. And you've got to run for office.

Bratt harbors no doubts that sexism is partly to blame for Huerta not earning the recognition she deserves.

"That's one of the things the film shines a light on. We do live in a patriarchal theocracy and women do get marginalized and so do people of color. So I think one of things that we were in mind of as we made the film was who controls the narrative," Bratt told us. "To this day, 2017, Dolores remains stricken from the social studies curriculum that was legislated by the Texas School Board... Dolores, she challenges the three kind of pillars and foundations of the culture which is capitalism, patriarchy and white supremacy, and I think that makes her very dangerous and makes a lot of people, particularly on school boards, uncomfortable."

Donald Trump's election as president has jeopardized essentially everything Huerta has spent her life trying to promote: workers rights, environmental protections, a respect for diversity and recognition for the value, humanity and contributions of people of color. Trump's rise to power likewise has brought a resurgence of the white supremacist movement, most recently underscored by Trump's expression of support for neo-Nazi, KKK and white supremacist marchers in Charlottesville, Virginia.

For Huerta the virulent display of white supremacist sentiment is nothing new. "t's becoming visible. It's always been here, to kind of justify slavery and treating farm workers -- like not giving them toilets -- treating them like animals," she told us. "That's kind of like that domination, to justify not paying working people and it still continues to this day."

The Trump era can be seen as a major setback to those who agree with Huerta's philosophy on human rights, but Huerta herself remains determined. She continues her work through the Dolores Huerta Foundation, focusing on civic engagement, voter registration and education, among other issues.

"This is what we have to teach in our schoolbooks, in pre-kindergarten," she declared, "because that's where racism begins. Teach this history of the contributions of people of color in building the United States of America so our children of color are empowered and our Anglo children are enlightened." Bratt commented on what we can learn from Huerta in these times of anti-immigrant sentiment and white rage. "One thing people can take away from Dolores' example of her life, but also her work, is that we can't get discouraged no matter what [Trump] does, no matter what laws he legitimizes, no matter who he pardons, we have to stay engaged," the director said. "You see the ups and downs and the curves that her life took and she's still as passionate and engaged as ever. We need to take our cue from that."

|

AuthorMatthew Carey is a documentary filmmaker and journalist. His work has appeared on Deadline.com, CNN, CNN.com, TheWrap.com, NBCNews.com and in Documentary magazine. |

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

Proudly powered by Weebly

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

RSS Feed

RSS Feed