|

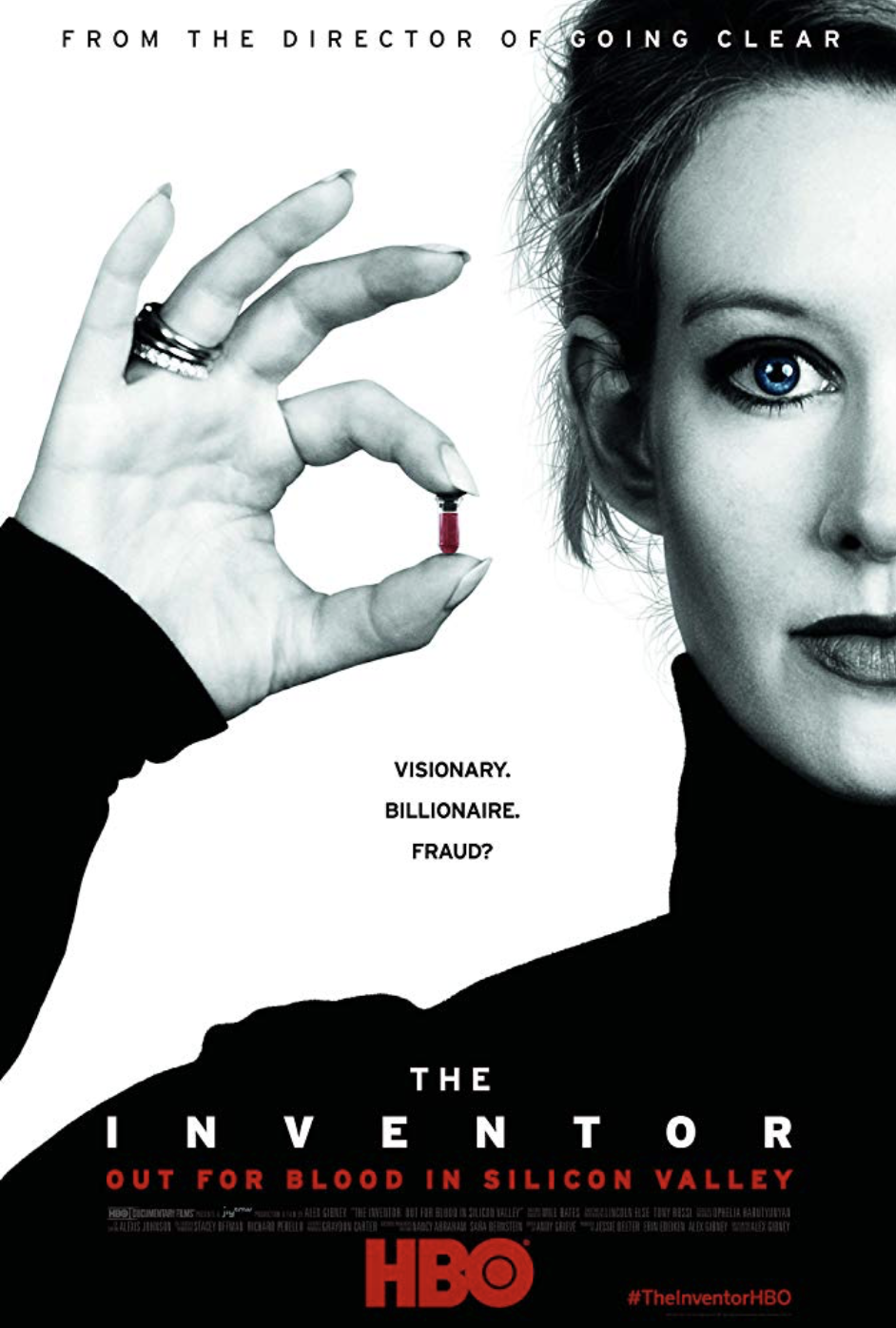

The film, subtitled Out for Blood in Silicon Valley, centers on disgraced Theranos CEO Elizabeth Holmes

HBO earned 138 Emmy nominations this year, more than any other network or streaming platform. The majority came for scripted series like Game of Thrones, but documentaries also contributed to the haul.

Alex Gibney's The Inventor: Out for Blood in Silicon Valley, scored its nomination for Outstanding Documentary or Nonfiction Special, a category that pits it against another HBO documentary, Dan Reed's Michael Jackson expose Leaving Neverland. Gibney's film focuses on Elizabeth Holmes, the once high-flying tech entrepreneur who turned a medical startup into a billion dollar business - at least on paper - before it all came crashing down amid fraud charges. Her vision of wanting to be the next Steve Jobs and her medical vision were sort of rammed together in this dream that could never really be realized.

The New Yorker called Holmes “sphinx-like” and inscrutable. Forbes described her as a con artist of super-human skill. Gibney, an Oscar and Emmy-winning director, is not quite so categorical in his assessment of Holmes, who managed to impress a diverse array of investors - not to mention former secretaries of state Henry Kissinger and George Shultz - with her business acumen before Theranos collapsed.

Nonfictionfilm.com spoke with Gibney about his Emmy nomination and the phenomenon of Elizabeth Holmes. The inventor has really resonated with audiences and kind of broken through. Is that your sense? And if so, why do you think that is? Alex Gibney: The simple answer is I don't know... The way it broke through kind of surprised me in the sense that now on Twitter they're things like hashtag #TheranosThursdays where people dress up as Elizabeth Holmes and take selfies of themselves. The longer answer is I think it has to do with people have a fascination with frauds, people have a fascination with Silicon Valley and led by a woman in male-dominated Silicon Valley, it seemed like a kind of trifecta.

What was the product Elizabeth was selling? And what were the origins of her deciding that this was a viable product?

AG: The origins go back to when she's a student at Stanford and she has this vision of some kind of device to do blood testing and maybe even to administer medicine simultaneously, with a patch. But that ultimately morphs into her idea of creating a machine. And it was always very important that it be a machine. Creating a machine that was small, that could do somewhere between 200 and 1,000 different kinds of blood tests with a very small sample. Notably, kind of a finger prick of blood. And so you would eliminate the need for a venous draw with a long needle and the plunging of that needle into the flesh is something that Elizabeth regarded as something akin to torture.

Her machine was supposed to be able to perform these numerous tests with a minuscule sample of blood collected in a "nanotainer." But there doesn't seem to be any real scientific basis for thinking that would work.

AG: It's not like there aren't machines that can test blood. Of course they do, all the time. And it's not like you can't test blood with small samples. I think the problem came when she wanted to have a machine that was kind of consumer friendly that would do all those things. And she was obsessed with that and wouldn't be dissuaded from her mission. Blood machines could do some of those things, just not ones that are pint-sized - well, not pint-sized but sort of Xerox machine-sized, and I mean a small table top Xerox machine, that can do them all. She wanted it to be a consumer device, that was one thing. So her vision of wanting to be the next Steve Jobs and her medical vision were sort of rammed together in this dream that could never really be realized. She wanted to be an inventor. Honestly, that's so important to this story, that's why I called it The Inventor. It was critical to her, not that she adapt something or just find a small change, she wanted to be a paradigm shifter. Right? She wanted to invent something brand new, something terribly important to her and her self image.

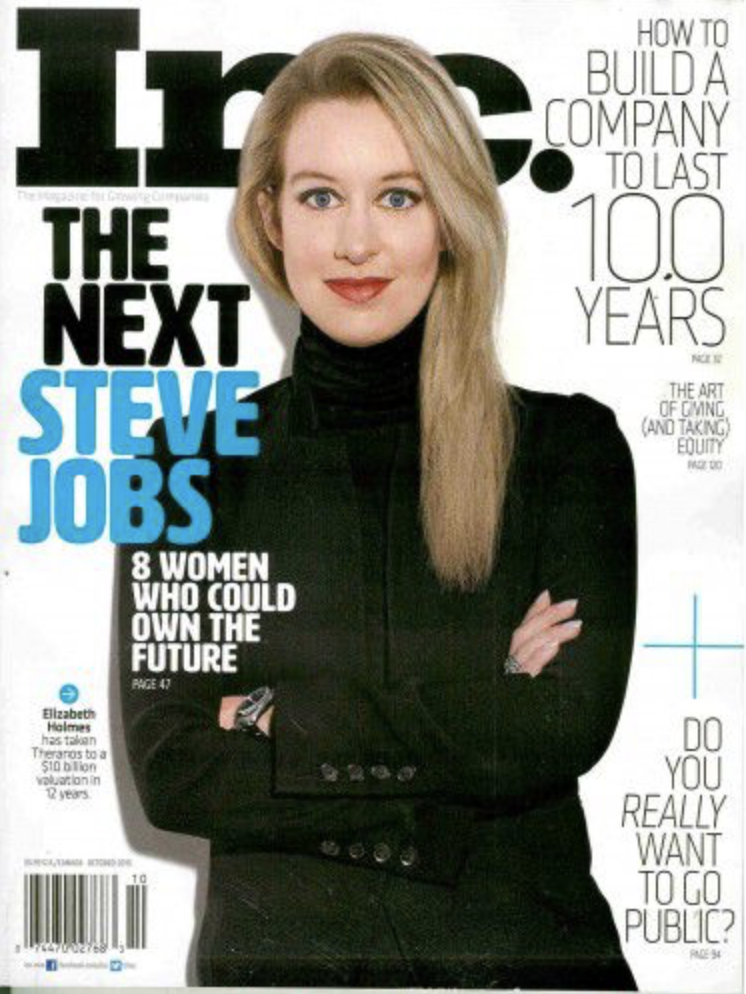

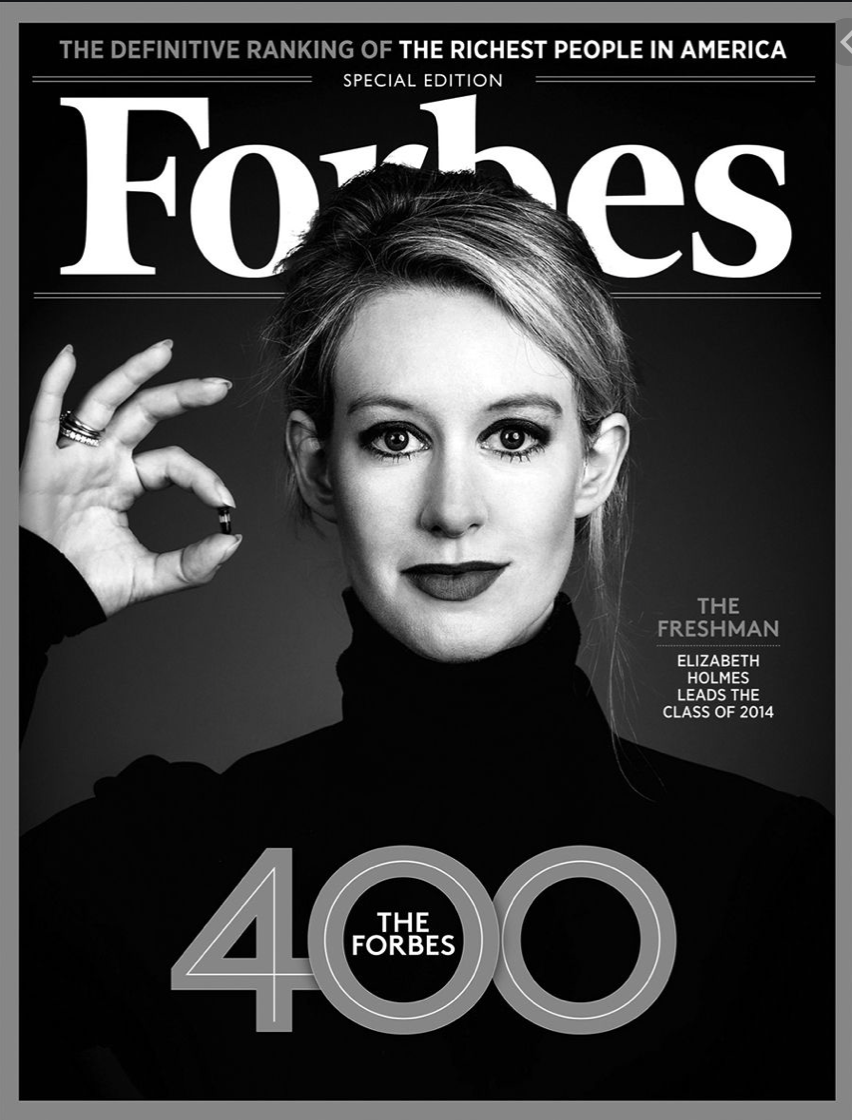

A selection of magazine covers from when Elizabeth Holmes was riding high

The question about Elizabeth Holmes inevitably comes down to whether she was trying to do good or if she a grifter from the get-go.

AG: Did she have good intentions? I think the answer's yes. She had good intentions in that she wanted to do something good and she had good intentions in the sense that she had a vision of herself as accomplishing that good that she wanted to fulfill. So yeah, I think that is true. Because if she had only wanted to make bank, she could have siphoned a lot more money out of the company than she did. I mean, she may have been looking for the big score, that's possible. But I think at the end of the day she wanted to fulfill a vision of herself. That was more important than just making bank. Clearly, whatever vision she had she was able to convince a whole lot of presumably sophisticated and wealthy people to get on board. How was she so successful at that? AG: I think by all accounts, and I've never met her - my producer met her and spent some hours with her but I've never met her - but by all accounts she was a tremendously charismatic and persuasive person. And we know this to be true because she once walked into a board meeting where they were about to fire her and she convinced everybody - and they were very experienced people in the room - that not only should they not fire her but they should keep her exactly where she was. So she was terribly persuasive. I also think she was pitching a vision that people really wanted to believe in. She was pitching a vision of doing something good for people, accurate blood testing, people could take better control of their own health care. And also, particularly for young women in Silicon Valley, she was pitching a vision that was empowering. You have a woman who's an inventor who is going to be an entrepreneur and make a lot of money while doing good. I mean, it's a compelling idea. And, lastly, I think she was seductive. I mean, I think for those older, white men, they were seduced by her. I think that is true.

In 2014 you did a documentary on Lance Armstrong and it occurred to me that there are certain parallels between his story and Elizabeth Holmes'. What parallels do you see between her and Lance Armstrong, if any?

AG: Let's look at one, which is Lance was telling a lie that a lot of people really wanted to believe. And that lie was that you could come back from cancer, you could be a cancer survivor, without doing any performance enhancing drugs you could come roaring back and win the Tour de France. So you could come back from the edge of death and not only survive but excel. That was a powerful myth that a lot of people depended on and wanted to believe in, thus those yellow wristbands. And I think the other thing that she and Lance shared was that when it came to going after people who were challenging the lie, she could be very ruthless. She and Lance were both very ruthless and very aggressive. Editors note: Ultimately, the Edison didn't work as touted and there were allegations Holmes manipulated test results and other data to make it appear the machine was doing what it was billed to do. The company's value plunged and Holmes and her second-in-command, Sunny Balwani, were indicted on fraud charges. It appears Holmes and her chief deputy, Sunny Balwani, will go on trial next year on 11 counts of conspiracy and wire fraud. I believe she's in San Franciso, in the meantime. I gather she has ditched her signature black turtleneck look in favor of something less imposing. AG: Yes, open collar now, as she wore in her interview with Maria Shriver where she's supposedly coming clean. She has a completely different look. This is a woman who is an inventor in every sense of the word and she had reinvented herself in that context. |

AuthorMatthew Carey is a documentary filmmaker and journalist. His work has appeared on Deadline.com, CNN, CNN.com, TheWrap.com, NBCNews.com and in Documentary magazine. |

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

Proudly powered by Weebly

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

RSS Feed

RSS Feed