|

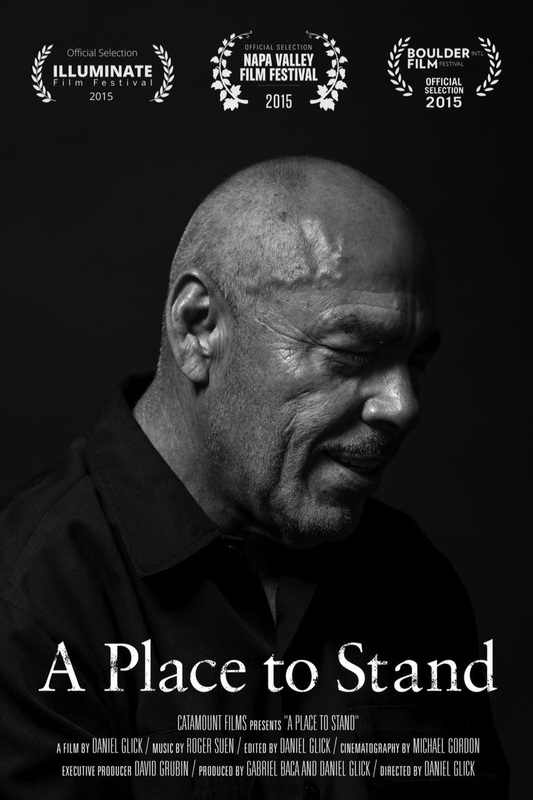

Daniel Glick's A Place to Stand set to screen as part of Awareness Film Festival in LA

One of America's most celebrated poets wasn't born to a prominent family (like Robert Lowell) or to a cultured clan (like William Stafford) or educated at the best schools (like Robert Fitzgerald).

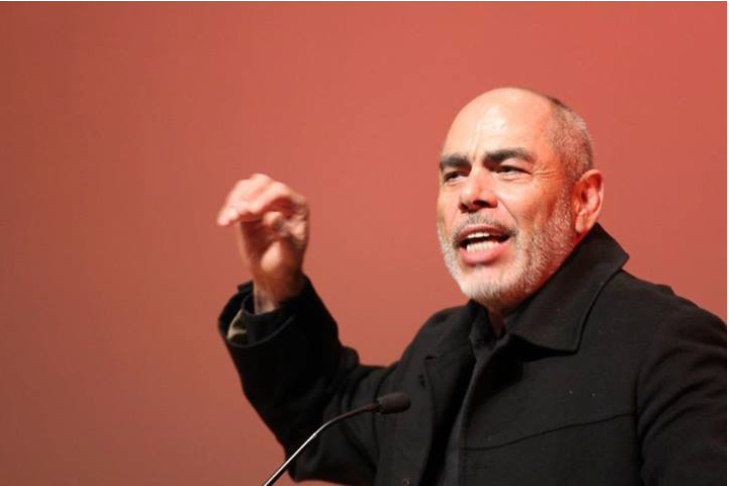

Jimmy Santiago Baca was born into poverty, abandoned by his parents and began his literary education behind bars. Despite his unpromising background he would go on to win the American Book Award, a Pushcart Prize and the Hispanic Heritage Award for Literature. His remarkable transformation is told in Daniel Glick's new documentary A Place to Stand, based on the memoir Baca published in 2001. He went into prison... reading at a first or second grade level, if that. In the span of four and a half years he went from basically illiterate to a published and celebrated and beloved poet.

A Place to Stand plays at the Awareness Film Festival in downtown Los Angeles on Tuesday night, October 11 [details here] and is now available on a variety of VOD platforms,including iTunes.

SHARE THIS:

Baca, 64, was born in New Mexico of Native American-Mexican heritage. He was raised for a time by his grandparents and then later sent to an orphanage. At 13 he ran away and at 21 he was sentenced to the draconian maximum security Arizona State Prison after he was convicted on a drug charge. He could easily have followed a wellworn path or recidivism, his name never to appear in print, unless perhaps on a crime blotter. Baca's memoir, which details how he transformed his life, got into Glick's hands by serendipitous means and eventually led to the documentary project. Nonfictionfilm.com talked with Glick about his film and the lessons that can be drawn from Baca's experience in one of the harshest of America's prisons. Nonfictionfilm.com: How did you first hear about Jimmy Santiago Baca? Daniel Glick: Through a friend of mine. I was living in New York at the time and I went with a friend to visit her pen pal who was in Auburn prison in upstate New York. I hadn't been to a prison ever. Auburn is a pretty intense one to go to... It was immediately shocking and I started thinking, "Oh, I've got to make a movie about prisons," within seconds of walking through the entrance. Just the misery of the place hung on everybody -- the guards, the inmates, visitors. It was incredibly oppressive and got me thinking, "Nobody's going to come out of here better for it. This is not rehabilitation." I talked to my friend's friend -- Tommy -- who had been incarcerated at Auburn for more than 17 years. He told me, "If you really want to understand me or understand prison you should read A Place to Stand. It's an incredible book." After I got home I bought Jimmy's book and really devoured it in a couple days. That book was another shock about what prison is in America. And simultaneously it inspired me because Jimmy's story is incredibly positive at its heart. As soon as I finished it I sent Jimmy an email and asked if I could make a movie based on the book. He said yes, after like four days of going back and forth.

NFF: How long ago was that?

DG: That was 2010. I quit my job, I left my apartment, I dropped my entire life. I bought a one-way Greyhound bus ticket to New Mexico and then my cousin gave me her car out of the blue so I didn't need to take the Greyhound. NFF: Was it hard gaining Jimmy's trust or confidence? DG: I think so, in some ways. In some ways Jimmy was incredibly open from the beginning. What I had going for me is that I immediately teamed up with one of Jimmy's sons who is a filmmaker, Gabriel Baca. Me and Gabe were the core. He produced it, I directed it. Having that "in" definitely made it easier. But I think it took Jimmy a couple of years to really trust us. The prison did nothing but try to break him. This was one of the worst prisons in the United States at the time. Incredibly violent, incredibly dangerous.

NFF: Describe Jimmy's background.

DG: Jimmy's roots, his background, is very similar to the background of a lot of people who are incarcerated -- severe family dysfunction, abandonment, abuse, neglect. A lot of suffering and tragedy. Jimmy was raised in that space of suffering and poverty and racism and marginalization and criminalization. Predictably, in a way, he fell into crime and then started dealing drugs and got caught and then went to prison. His background is not so unique. He went into prison basically illiterate. Functionally illiterate. Maybe reading at a first or second grade level, if that. In the span of four and a half years he went from basically illiterate to a published and celebrated and beloved poet who was one of the most buzzed about by the time he got out, both in urban circles but also in the poetic aristocracy of New England... He was published in all these prestigious and amazing places. He underwent this radical transformation primarily by himself, without the help of the prison at all. The prison did nothing but try to break him. This was one of the worst prisons in the United States at the time. Incredibly violent, incredibly dangerous. It was corrupt and the warden hated Jimmy. There was a lot of brutality and violence and threats all around him. And yet in the environment he decided he was going to do something different. He decided he was going to write poetry and defy the prison. I love you,

NFF: There's a moment in the film where he talks about being on the point of stabbing an antagonistic prisoner, but he had a kind of vision telling him that if he did that he'd never become a poet.

DG: Of course he got caught up in the crime of the prison, he got caught up in the danger and the violence of the prison. He had to defend himself, he had to fight. But he was able in that crucible -- like a literal hell -- to do a complete 180 and radically improve his life and find love and joy and compassion... by force of will and passion. He is one of the most dramatic examples of human transformation that I have ever seen or encountered and he is living proof that anyone change their life if they have the courage and conviction to do it and a direction to go in. NFF: You did not take a cinema vérité approach to the narrative, like showing Jimmy at home, walking around, getting coffee, etc.. It's really him on camera, relating his story. DG: From the beginning Gabe and I said to each other, quite often, our job as much as possible is just to let Jimmy tell his story and get out of the way. We tried to not put anything in there that was excessive or indulgent... The meat of the story is his journey in prison. It's not so much who he is right now, although that is interesting too. It is his journey in prison so let's stay there and let's fully immerse ourselves in this transformation which is at the heart of the story... We fought hard to make it so that whatever visuals we put in the film didn't feel like a History Channel reenactment. We interviewed some of his famous friends like Helen Mirren and Taylor Hackford, the director, some of the actors who were in Blood In, Blood Out [based on a screenplay by Jimmy]. We didn't end up using any of them in the film.. My sense is that if we had included some of that we may have gotten into some bigger film festivals than we did but it wouldn't have had the power of the story that we wanted. So we tossed out all of that stuff... We really just focused on how he became the poet. I continually find myself in the ruins

NFF: There are some amazing visuals of the prison. Is that the actual place where Jimmy was incarcerated?

DG: No, it wasn't. It was a prison in Montana. We weren't able to get into the prison in Arizona because it's still active. We found an old prison museum that was built around the same time as the one in Florence [Arizona] and that had very similar designs and cells and cellblocks. It looks the same as Jimmy's prison. The fact that it was abandoned gave us the freedom to just run around and roam around without having to worry.

NFF: By implication your film has a lot to say about the penal system in the United States, which overall seems to emphasize the punitive versus any kind of effort at rehabilitation. Do you hope viewers give that thought?

DG: I do hope that people will reflect on the nature of prison and the purpose of prison... Our hope was to point out vicariously what it's like to be in prison as an individual. If you really look at and feel what Jimmy went through then it obviously brings up a lot of serious questions about the efficacy of prisons in America and what is the point. He came out with these amazing gifts but he came out with demons too.. He was not unscathed. Right now prison fucks people up more and it makes people worse, by and large.

DG: If rehabilitation is the goal we are failing spectacularly with our prison system. Part of the message of the film is convicts are just human beings who fucked up. And a lot of them fucked up because they were fucked up by others when they were younger... Right now prison fucks people up more and it makes people worse, by and large. There are exceptions, but by and large people come out worse for the wear. It's one percent of our population. We imprison more people than any other country in the history of the world including Soviet Russia. It's costing us an incredible amount of money. It costs more money to incarcerate somebody for a year than to send them to Harvard for a year. There is a severe brokenness to the system and it treats human beings as less than human beings.

NFF: What are your plans for the film going forward? DG: It's available on almost every digital platform -- iTunes, Amazon, YouTube, cable and satellite providers. Also available for educational institutions. We want to get the film into as many prisons and schools as possible and have it be used as a tool for education and rehabilitation. That's the most important thing for me. |

AuthorMatthew Carey is a documentary filmmaker and journalist. His work has appeared on Deadline.com, CNN, CNN.com, TheWrap.com, NBCNews.com and in Documentary magazine. |

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

Proudly powered by Weebly

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

RSS Feed

RSS Feed