|

The artist/musician/writer/filmmaker combines all her talents in innovative film

Laurie Anderson's inventive new film is not easy to describe.

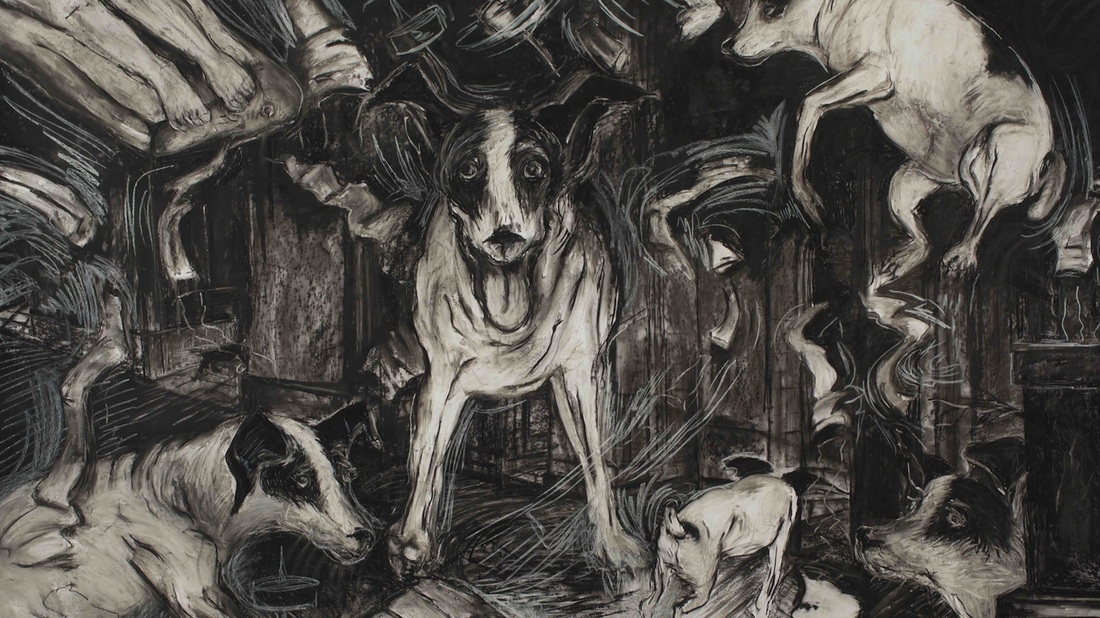

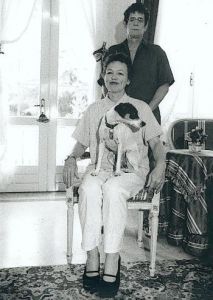

"It's been thrown in doc land, you know, as a documentary. It's not really that," the multi-talented artist/performer/composer/poet told Nonfictionfilm.com. So how then to characterize Heart of a Dog? "A playful, lucid and heartbreaking nonfiction feature on the life and death of her dog, Lolabelle," says the press notes for the film, adding, "Anderson creates a gorgeous, heartbreaking tapestry on love and loss." One could also add that it is a meditative, personal film full of wisdom and visual and aural poetry. With laughs. Yes -- it is funny, too. Dogs in clogs, dogs at the keyboard funny. It doesn't have to be called a documentary or not. It's just a film. It's stories and what they are. It's not that complicated.

Heart of a Dog is now playing at the Nuart Theatre in Los Angeles, with a national run to follow [theater information here]. It will premiere on HBO in 2016. Nonfictionfilm.com spoke with Anderson in West Hollywood about her film, Wittgenstein, language, French Structuralism and Lolabelle.

Nonfictionfilm.com: This is a challenging film to sum up. How do you describe it, or how would you prefer it be described?

Laurie Anderson: I don’t mind trying to describe things. I think that’s really helpful sometimes. In this case it was commissioned as an essay film by Arte TV - a French-German channel -- and they said, “We want you to do a film that’s like an essay.” [I said], “What is an essay film? I’m not even sure what that is.” It's not the story of me and my dog and getting to know us... Stories and how they’re made is the actual subject of this. Now the French guy who commissioned this said, “This is a very French form. I don’t think Americans will really get it.” So I’m really happy that Americans seem to get this film and kind of accept it as whatever. It doesn’t have to be called a documentary or not. It’s just a film. It’s just a film. It’s stories and what they are. You know, it’s not that complicated. But he was very, very intellectual about it. And he [had this] like... French structuralist attitude towards art-making. And I’m a sucker for that. I love it. I love this kind of theoretical blah, blah blah stuff. But more than that I really like shaggy dog stories. So I started with my own dog [Lolabelle] and go, "Okay, what is it like to see through a dog’s eyes?"

NFF: The film has been described as a meditation on death, which I think is a very useful thing. I don't think I'm breaking new ground by observing that in this culture we don't like to deal with death. Do you find death something to fear? It sounds like you've reached a level of consciousness about it that others should entertain.

Laurie: I don’t know. It’s not a “should” for me at all. I try to be very light-handed about all of this because, for example, everyone who's had a dog or a cat that they really felt close to — another creature — has this dilemma of like, "Okay, now we have to put them down.” And it’s just a horrifying idea. And everyone has a different attitude towards that. I tried really hard not to say, “It’s really good to do that or it’s really bad to do another thing.” But it is the American way of death to try to kind of clunk you on the back of your head with a brick and just make sure you’re not in pain and not even there. Not even there. So one of the teachings of this guy who’s very central to the film — Mingyur Rinpoche — he said among other things, "Try to practice how to feel sad without being sad." It’s just kind of basically saying, “Show up. Show up for it. Be there. Try to be there if you can.” And not just kinda go “Oh, that’s going to be scary and sad and awful.” Because the world has a lot of sad things and a lot of suffering and if you push it away it’s going to come and bite you. It’s going to find you. You can’t really push it away that well. and pretend it’s not there. It’s there. But his idea is to kind of acknowledge it but don’t become it. That’s so important. Do not become the sadness. He’s convinced that we’re here to have a really, really, really good time. That’s what we’re here for. That’s how he sees it. NFF: A comforting thought. Laurie: It’s a great thought. NFF: Of the available philosophies that’s one we should be able to embrace. Laurie: I can totally identify with that. So that’s one of the sort of basic things in this [film]. If I were Woody Allen I would call it "Love and Death." But I’m not. So I had to call it “Heart of a Dog.” Because it’s as much about love and what that is as identity and loss of your identity at death. NFF: There’s a wonderful line in your film: “The purpose of death is the release of love.” And I don’t quite know what it means, and maybe that’s okay. Laurie: That is okay because I don’t quite know what that means either. I’ve lived through it and I know that that’s how it kind of works. But do I really know it? No... You could look at it as a certain kind of energy that gets released, and [that] makes a certain amount of sense. But the complexity of those things is also — [I was] just thinking of F. Scott Fitzgerald who as a writer said, “You should try to imagine you’re holding two very opposing thoughts and they’re both equally true. And they are equally the opposite. And try to learn how to hold both of those without going crazy.”

Laurie: There are a lot of things that are complex. And it’s not like, “This is right!” You know, they’re kind of both right. They’re situational. This is a situational film. There are things that are true and not true and you’re left in a way to have to come into it in many different ways -- sometimes through the eyes of a dog, sometimes through the lens of a surveillance camera, sometimes you’re floating around freely in the Bardo. "Where am I? Where is this?" And [it's meant] to be a series of of questions about how you construct your world, really. And who you are in it. So those are disguised as stories about me and my dog. I mean not disguised. That’s the texture, that’s the meat of it. That’s the way it works. But what it’s trying to do is something different than that. It’s not about getting to know me at all — a biopic of like “Here’s who I am.” I say a lot of very personal things along the way because I’m not trying to be mysterious or anything like that. I’m trying to look at how you can be truthful in certain ways.

NFF: One thing you're very truthful about is your mother. Laurie: One of the things that really surprised me was the number of people who said, “Can you say that you don’t love your mother? That’s okay?” Well, I did say that. NFF: That was kind of transgressive. I don’t know if that’s the word. Laurie: It is transgressive in our culture. Because women are expected to transcend all of that and, no matter what, be these huge and perfect beings which — women are just like everyone else. They have their limitations too. But I think that it’s not allowed for women to say, “Gee, I didn’t love that child, my child.” You can’t say that. NFF: Right. That would be a big taboo. Laurie: It’s a big taboo. And that’s why the mother meditation is key to Buddhism. You can always find a millisecond of a mother loving her child. Doesn’t have to be long. Can be a millionth of a millisecond but there is one moment when there is absolute pure love. And if acted upon or done in a perfect way it is there. Because it’s life. That’s what it is.

NFF: You have the wonderful quote from Wittgenstein in the film -- "The limits of my language mean the limits of my world." But music is a language, or certainly it communicates. Are there limitations — now we’re debating Wittgenstein —

Laurie: Always interesting NFF: — are there limitations in thinking that language delimits our reality? I mean you’ve got music... Laurie: Of course we know that’s crazy. Just because you can’t say something doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist. That’s insane. It’s the fallibility of language. A lot of things you can’t put into words. A lot of emotions, even thoughts that have a complexity that we don’t actually have words for and it absolutely doesn’t mean that they don’t exist. I mean that’s why this is a film, not an essay, not a written essay made of words because the world is full of meaning that you can’t say. You look at a tree and it’s moving so freely against a sky that’s so blank. It has a lot of meaning and it also has — it’s imprinted in your past in a way too— it might be reminding you of some other day from long ago. It’s full of meaning and not very many words... Why would you [need to put everything into words]? You don’t have to in this world of imagery and memory and sounds. And that’s why people make paintings and that’s why they make music. NFF: In the film you relate how music became very important to Lolabelle after she lost her sight. You got her music lessons. Laurie: Lolabelle was like a lot of humans. I mean music saved her life. It literally did. When she started to play she was able to create a world of music that she lived in. A lot of dogs do really well when they go blind. They’ve got an amazing sense of smell, great sense of place, they have incredible hearing. Their eyesight’s not that good anyway. But she was the kind of dog that’s glued to people and needs to recognize them... She completely panicked [when she went blind]. And her whole world was lost. She just wouldn’t do anything. We had to pick her up and do everything. That’s why she began to do music as a way to amplify another part of her sense so that she could live in there. That was her story. My dog now — little Will is also in the film. He has the cameo role of the little dog who has the little clogs, he’s walking through the rain. That’s my current dog. He was not happy about wearing the clogs. But he’s a really good sport. He does not play piano. He does not paint. He’s a great dog. He’s just very sporty and he loves to eat. That’s kind of a big hobby with him. NFF: It's hilarious to see little Will walk in the rain in his clogs. That's a wonderful and surprising thing about the film -- at times it's very funny. Some of the humor comes just from the way you deliver your voiceover. How was it in general for you to record the words? It sounds effortless. Laurie: The pacing of it was the interesting thing to try to do right. Sometimes I really wanted to like rattle through a story really fast so you would drive through it and then other times the language was very sparse. So there are a couple of little hidden poems in there, like “What Are Days For?” these kind of questions that are just hanging there for a while. But then sometimes it’s just silence or some very fragmented violin too. I tried to place it so the story wouldn’t be so relentless that you’re just like, “Stop talking!” I didn’t want it to be really obnoxious but more like sort of moving to the stories that had a kind of casual pace, not sort of formal or anything. NFF: You dedicate the film to your late husband, Lou Reed. Were you able to share the film at all with him before he died? Laurie: Oh yes. He saw a lot of it and also he’s in everything in there because all the stories that I write and my writing style is really — in a lot of ways we helped each other. He was always very clear about not using too many metaphors. He was just like, “Why don’t you just say what you mean?… Do you really need that metaphor? Just say it." So his spirit is really there. I started the film but when he got very sick I stopped working on it. I wasn’t thinking about going back to it at all. And then an editor just kept working on it a little bit and said, “Have a look at this cut and this cut.” So without her I probably wouldn’t have finished it. That’s Katherine Nolfi. NFF: The film has earned tremendous praise. Laurie: It’s been really interesting. Since it was this European production I’m really happy that’s it’s been understood in [the place] where it came from. NFF: That’s showing the Europeans something! Like, hey, you discounted those Americans. They can surprise you now and again! Laurie: We’re not the idiots you might think we are.

|

AuthorMatthew Carey is a documentary filmmaker and journalist. His work has appeared on Deadline.com, CNN, CNN.com, TheWrap.com, NBCNews.com and in Documentary magazine. |

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

Proudly powered by Weebly

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

RSS Feed

RSS Feed