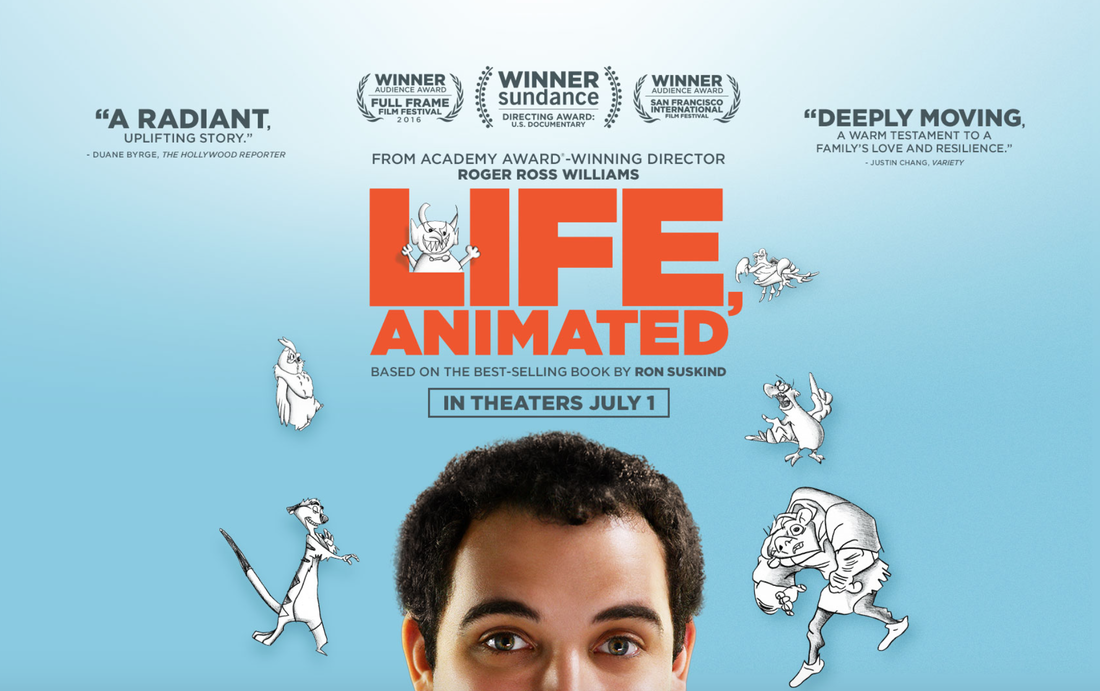

Heroes and sidekicks: 'Life, Animated' explores how Disney classics proved salvation to autistic boy7/2/2016

Oscar winner Roger Ross Williams directs inspiring, touching doc on Owen Suskind

Disney animated films have entertained millions of children over the decades, from Snow White in 1937 onward.

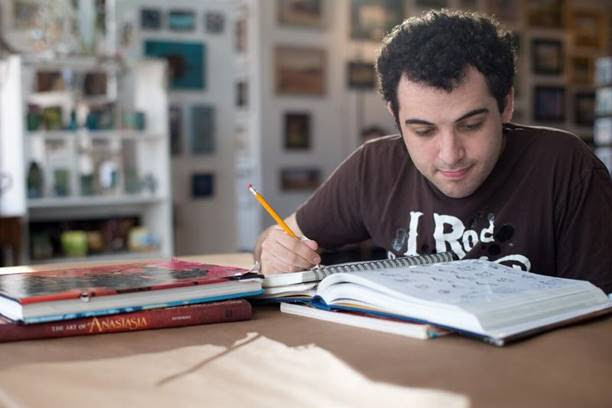

But for at least one youth with autism those films provided much more than just entertainment -- they became his lifeline to his family and the outside world. The remarkable story of how Owen Suskind learned to communicate through Disney films is told in the new documentary Life, Animated, directed by Roger Ross Williams and based on the book by Owen's father, Ron Suskind. He really creates a place of survival. He turns stories into a vessel that now he drives into the world -- in a way just like the rest of us, but more so. With more at stake.

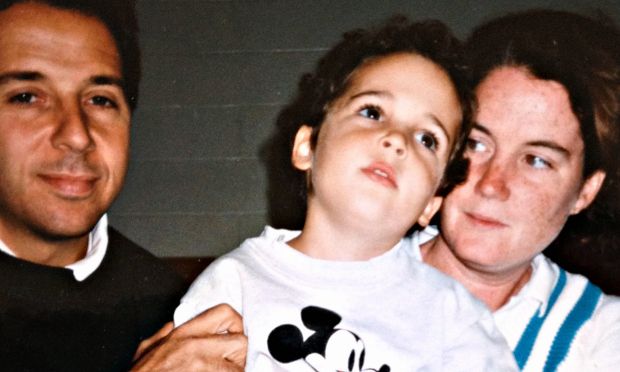

Owen Suskind appeared to develop like a "regular" kid until at age three he suddenly went silent, retreating to an interior mental space that his parents, Ron and Cornelia, struggled to access. He was eventually diagnosed with "regressive autism" and the family was told he might never speak again.

The world of Disney animated films absorbed him, however, including The Little Mermaid. And one fateful day Owen's parents realized a seemingly garbled word he uttered was actually a line of dialogue from that film. They would discover he had totally memorized all the Disney films he loved. And it wasn't simply that he found the stories diverting -- he was studying them intently for life lessons. They were his Rosetta Stone, the key to decoding a confusing world.

He says we're all really sidekicks -- at our best when we help others fulfill their destiny, which of course is the job of the sidekick, to help the hero fulfill his destiny or her destiny.

His mother, father and older brother Walt began to converse with Owen via characters in the films -- Ron at first using a puppet to talk in the voice of the parrot Iago from Aladdin. It was sidekicks like Iago with whom Owen most closely identified. Over time he regained the use of speech to a degree that would have shocked the doctors who first diagnosed him.

Life, Animated opened in New York and LA on Friday. It expands to more cities in the coming weeks. Nonfictionfilm.com spoke with director Williams and Ron Suskind in June just before the film played at the Los Angeles Film Festival.

Nonfictionfilm.com: I think of the film as a love story, the love of a family for their son. If these were not parents who cared and loved their son deeply they wouldn't have been as observant, they wouldn't have seen the pathway into his world. Roger Ross Williams: It's absolutely a love story. Definitely. Cornelia is the world's most amazing mother and inspiring. Walt is the most amazing brother. For me, why I think I was so passionate about making this film is because I come from a broken family and to see a family who cares so deeply for their son and for each other just melted my heart. It's as much about that or more than Owen's struggle with autism. It's really about this family and their love for each other and overcoming this huge sort of obstacle in their life which ended up not being an obstacle, it ended up being a gift. Ron Suskind: Love is at the center of our life and the center, in a way, of what we learn. We learn new and deeper ways to love each other. Owen and [his] struggles challenge us... What we find is that it's about the power of story. That's also the life we wound up living beyond anything we could have imagined. We were already kind of a story family. I mean Cornelia and I are writers, for goodness sake. But this idea that we really need stories to survive is something we learn through our conversations, the whole family, with Owen, because he really creates a place of survival. He turns stories into a vessel that now he drives into the world and in a way just like the rest of us, but more so. With more at stake.

NFF: We consume narrative all the time. I've often thought that maybe part of the appeal of narrative is that our lives have such a narrative structure -- a beginning, middle, and an end -- that's kind of imbedded in us. It's fascinating to get that glimpse of how Owen is able to interpret the outer world, if you will, through the means of Disney animated films.

RS: That's I think part of the resonance of the movie is that people go, "Wait, I do some of that, too." But I certainly didn't have to do it with a kind of depth and almost exclusivity [of Owen]. Owen's like running a 10-year, 20-year Joseph Campbell experiment. He's on a desert island in a way with 50 Disney animated movies, classics made since Snow White in 1937. "Here you go, see you in 10 years. How much can you learn and draw from this diet of myth and fable and legend to make your way in the world and to understand who you are at the deepest level?" That's the experiment he runs in a way for the world. How powerful can it be when you have to turn to it so ardently, with so much at stake. And of course you see now this young man who walks the world and he seems like one in a million but more and more as people come to us at screenings all across the country we're like, he may be one of a million or of many million who now see this with new eyes, what story can do to your life. That hyper-focus in finding things in the wider world and then applying them to the stuff of life is something that people with autism do.

NFF: What do you think we can learn from people with autism?

RRW: As a filmmaker during this journey I learned so much from Owen about story. In a way it helped me become a better storyteller from what I learned listening to Owen. But I think from autistic people in general, each of them with their particular affinity with the one thing they focus on, they have something to offer the world and it's time that we don't look away or that they're not to be left behind. It's actually to use that sort of laser focus -- for Owen it was Disney movies; for another person with autism it could be something else -- to sort of harness that and use that and learn from them, so not look the other way. That's what I've learned and I think that's what the message of the film is. RS: Temple Grandin, who is the famous person with autism, has a great line. She says, "You know, we all have autistic traits and without them the great developments within human history wouldn't have taken place." She says, "The person who created the wheel was probably autistic. While everyone else was socializing around the fire, making small talk, this person was going, 'I think this thing rolls. Hold on a second, let me turn it a little bit.'" That hyper-focus in finding things in the wider world and then applying them to the stuff of life is something that people with autism do, in ways that many of us can't. And I think people are seeing that through this film in a way that opens them up. What's that line from Proust? "The voyage of discovery is not about seeking new landscapes, it's about having new eyes." Suddenly they walk out of the theater with new eyes. And I think that's an exciting change for anybody.

NFF: It curiously tracks with the hero's journey described in Campbell, particularly about shamans. We need shamans because they go to a place the rest of us are too afraid to go or cannot access in some way. In a way Owen and other people like him are emissaries from a place we can't quite imagine. We don't quite know where they have been, where they are. And they come back to us with lessons.

RS: That's right on. And I think what this tells us is that when they [people with autism] leave or when they come back it's not because they don't want to be with us, it's that they're ready then to say, "Here is what I've found." And that's the moment where we must welcome them and say, "Tell me. Tell me your story. Tell me what you see that I can't." That's what opened our pores -- me and Cornelia and Walt and it does every time we meet folks who are neuro-distinctive or neuro-divergent in the parlance of the age-- and realize they are in fact differently abled. That's such a PC term, [but] it's reality. And that's what's so exciting about the movie in terms of its universal power. To me this was an emotional coming-of-age story and that's the story I wanted to tell.

NFF: In the film you relate how Owen at age three went into this world of silence and mystery. The film doesn't ask why that happened, for understandable and perhaps important reasons.

RRW: For me it was never about why someone has autism. Owen is someone who lives with autism -- it's about what does he have to offer us? What are his gifts to offer us? The film follows him for this year, this sort of transitional year for his life as he is getting older and moves in on his own and graduates -- all the universal things, but what does that mean for someone living with autism? To me this was an emotional coming-of-age story and that's the story I wanted to tell. So there are no real experts or doctors or anything like that. NFF: If you were to ask "why" that implies that there's something wrong. RRW: Yeah. Exactly. I started this film and I was uncomfortable. I didn't know anyone with autism and after the journey, I was like, 'Wow. Not only have I gotten to know Owen, but I've sort of gotten to really appreciate and understand people living with autism." I decided this was an emotional story, not a science film, so I took sort of all of that science stuff out. It's in the DVD extras.

NFF: The Disney animated canon is Owen's major focus. Does he not get into the Pixar computer-animated films?

RS: Disney was the first place, the hand-drawn animation. But over time he's migrated more and more. Pixar -- when the movies work in terms of deep narrative, he's on 'em. He loves 'em. And interestingly in the past few years he's branching out. Disney's still the base, but he's using that as a springboard to other live action movies of the more traditional, general interest brand. He focuses in on the the areas of deepest resonance and he uses them. Recently he's had some issues with breaking up with a girlfriend. He's had some tough turns. He came to me and Cornelia and he used Alfred -- Michael Caine from Batman, from the Christopher Nolan series. And he says to us, "This one part I hear in my head a lot." He says, in Michael Caine's voice, "Why, sir, do we fall?' "Why, Alfred?" "So we can learn to pick ourselves up." And he runs this in his head, just like we all have scenes and characters running through our head, living the modern life. And he uses that to pick himself up. NFF: Owen connects so strongly with those sidekick characters like Alfred in Batman or Zazu in The Lion King. RS: His view is original and different and an altering of the traditional narrative arc. He says we're all really sidekicks -- at our best when we help others fulfill their destiny, which of course is the job of the sidekick. This is what we do at our best, help others fulfill their destinies and on that day we find the qualities of the hero within ourselves but we are ever sidekicks and you don't get redrawn in this life, not really. It's totally great to film someone who can only tell the truth. Owen can only tell the truth.

NFF: You write in your director's statement how Owen is "not encumbered by social cues," which is such an interesting thought.

RRW: Which is so great. It's totally great to film someone who can only tell the truth. Owen can only tell the truth. As Henry Markram says, he doesn't have the bubble we all have around ourselves that protects us from the world. That bubble doesn't exist for people with autism. So Owen lives in the moment for a filmmaker because Owen was never focused on the camera, he was just living in the moment and living his life and that's why we were able to film him while he falls asleep and wakes up in the morning... If you woke up and there was a camera looking at you, you'd be like, 'What the...?" He completely ignores it. NFF: In the film we hear how Owen was bullied in high school -- there were kids who said they were going to burn his house down. You created an animated sequence that allows us to understand what that threat feels like -- it's real for him. RRW: My whole vision for the film was to show someone with autism from the inside looking out, as opposed to the outside looking in which is where most of the films you see - it's always from the outside looking in. And to go deeper and deeper into Owen's internal world and the way he sees the world and approaches the world... It's why he's the only one in the film who talks directly to the audience because it's all about Owen's perspective and Owen's world. Even the soundtrack is Owen's self-talking and the sound of VHS rewinding. We took that and Dylan Stark and Todd Griffin created a soundscape based on Owen's self-talk. That's what you're hearing is Owen's self-talking turning into musical language. Owen is constantly doing the dialogue of the sidekicks in his head who are his advisers in life, who are really guiding him through life. He's learned from these films... watching them hundreds if not thousands of times... so he's constantly in dialogue and doing the dialogue of the sidekicks. It was about taking that and really bringing that to life. |

AuthorMatthew Carey is a documentary filmmaker and journalist. His work has appeared on Deadline.com, CNN, CNN.com, TheWrap.com, NBCNews.com and in Documentary magazine. |

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

Proudly powered by Weebly

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

RSS Feed

RSS Feed