|

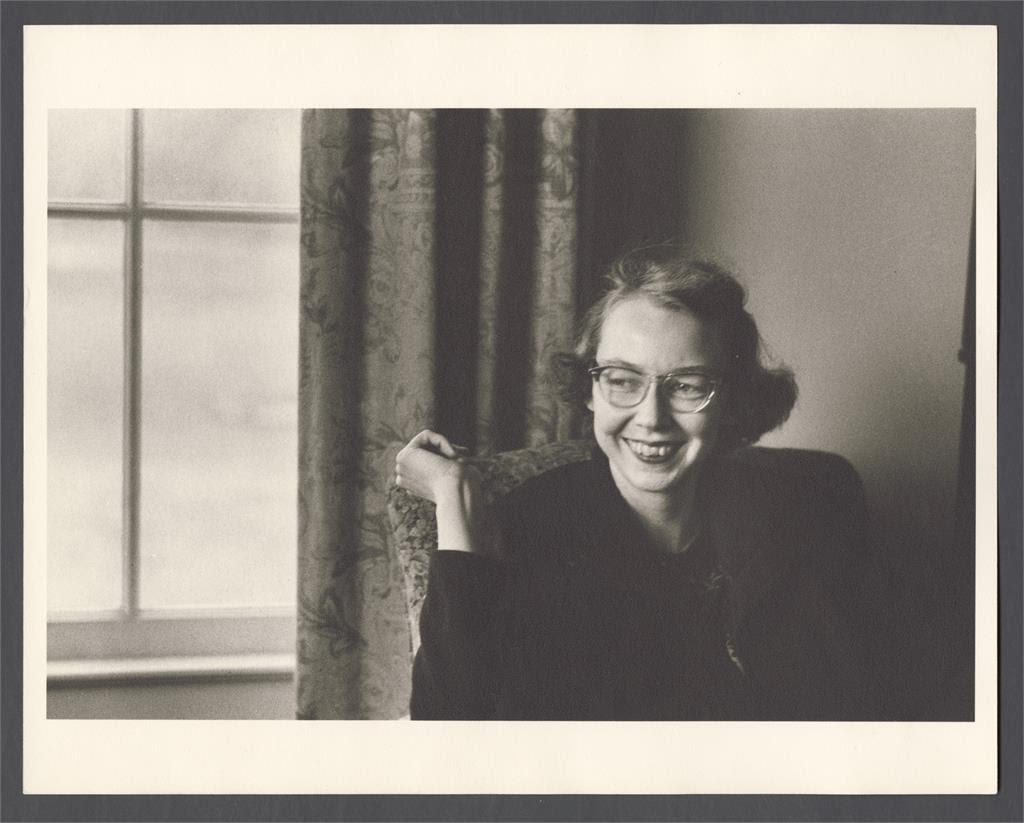

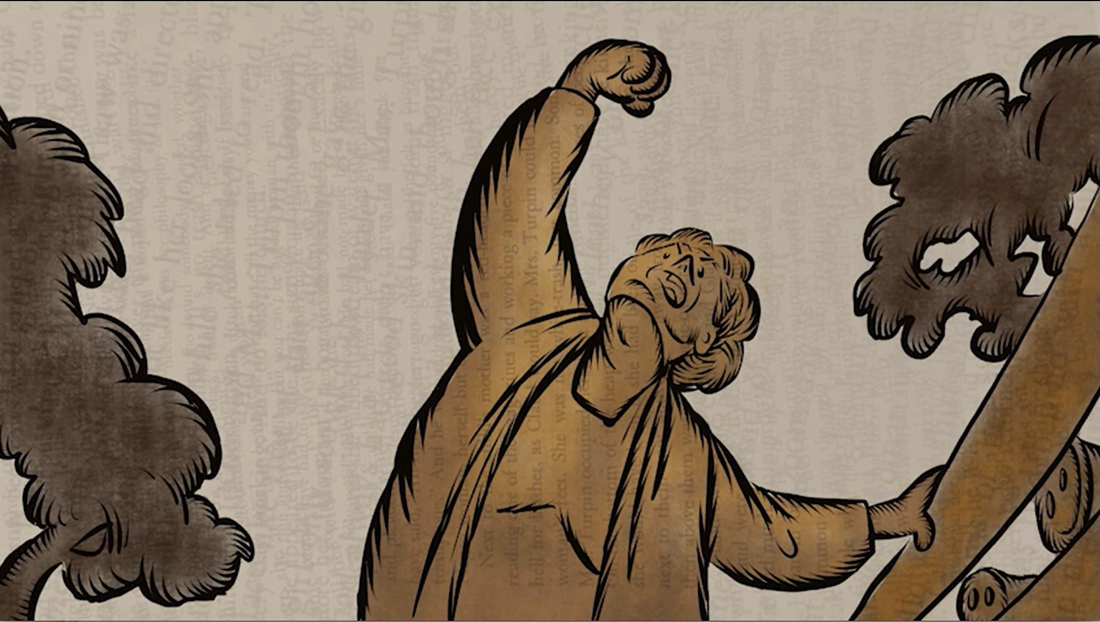

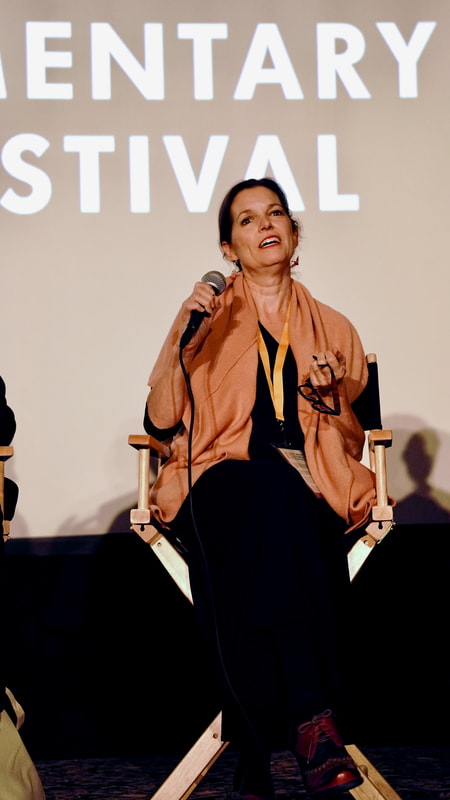

Film by Elizabeth Coffman and Mark Bosco explores 'under appreciated' literary great inspiring 'a whole new group of scholars, fans, artists' I first became aware of Flannery O'Connor as a teenager, introduced to her not in school but my father. Pressed among his stacks of nonfiction books, her collected works of fiction stood out - in part for the distinctive cursive script on the spines and their dust jackets festooned with peafowl (I would later discover the colorful motif reflected the author's love of peacocks, which she raised on her farm in Milledgeville, Georgia). To impress my dad, I began reading her stories and, indeed, I recall how pleased he was by that, as if it were a sign of growing intellectual maturity. But that initial motivation fell away and I entered into what might be called my own "personal relationship" with O'Connor (a bit like a Christian's personal relationship with Jesus?). She has that effect on you - fusing writer and reader in a joint pact of acute discernment. We aren't bystanders in Flannery O'Connor stories - we're ensnared in tales of moral judgment that implicate us as much as her characters. Musicians Bruce Springsteen and Lucinda Williams and actor Tommy Lee Jones are among the prominent cultural figures who have developed their own relationship with O'Connor. With the arrival of the new documentary Flannery, directed by Elizabeth Coffman and Mark Bosco, many new readers may be drawn to the experience of her work. She had an extraordinary genius about knowing how to use words, how to create images through words. "We're hoping that the popularity of the documentary will help to bring her name a little more back into the pantheon of great American writers," Coffman told me a day after the film held its world premiere at the Hot Springs Documentary Film Festival in Arkansas. "We have Tommy Lee Jones in the film saying she's one of the best writers of the 20th century and he read everything she's written. She's not just a great Southern writer, she's a great writer, great storyteller." From Hot Springs, Flannery headed to the New Orleans Film Festival, where it screened on Monday and Tuesday, with Coffman and cinematographer Ted Hardin in attendance. Last Thursday the documentary won the inaugural Library of Congress Lavine/Ken Burns Prize for Film, an award that comes with a $200,000 grant.  Filmmakers discuss "Flannery" after the film's world premiere at the Hot Springs Documentary Film Festival. L-R moderator and HSDFF director of programming Jessie Fairbanks, director Mark Bosco, director Elizabeth Coffman, cinematographer Ted Hardin, co-producer Christopher O'Hare. Friday, October 18, 2019. Photo by Matt Carey O'Connor was born into privilege in Savannah, Georgia in 1925. When she was 15 her father died of lupus, the same disease that struck O'Connor in her 20s. She would struggle without complaint from the illness for over a dozen years before lupus claimed her life, at age 39, in 1964. Despite the chronic pain she endured, O'Connor was able to produce two books of short stories (one of them published posthumously), two novellas, essays and copious letters to family, friends and acquaintances that were posthumously collected in The Habit of Being. "I think she's under appreciated. It's kind of gone in waves. In the 1970s after her death and at the release of The Habit of Being, the letters, there was a surge of people talking about her, writing about her and then it kind of died down," Bosco notes. "But there's been a new wave in the last decade or so and because of that this is such a timely moment for the film, because now that generation that kind of owned Flannery O'Connor - those critics and those friends like Sally Fitzgerald, they're passing. There's a whole new group of new scholars, new fans, new artists who are interested in Flannery O'Connor." As a craftsperson, absolutely, she is masterful. O'Connor's work is rooted in the red clay of Georgia, stories of wicked satire and shocking violence that touch on race, class and religion. She's described as a Southern Gothic writer, in the company of William Faulkner, Carson McCullers, Truman Capote and others, but even among them her writing stands apart. "I see what makes Flannery O'Connor unique among Southern writers, it's the way that she creates the story that's really grounded in universals and I really think it comes from her Roman Catholicism, to be honest with you," comments Bosco, a Jesuit priest and vice president for ministry and mission at Georgetown University. "There is a sense that truth, the sense of beauty and death and judgment is a cosmic question always for Flannery O'Connor and that she can concretize it in these finite, particular moments within the South. It gives a different kind of texture to her writing." Coffman first discovered O'Connor's writing as an undergraduate studying English. She immersed herself in the author's work as she began making the documentary. "As a craftsperson, absolutely, she is masterful," Coffman observes. "But also her issues, the issues of white racism, the issues of the Klan, these issues aren't going away... if anything they've come right back and we are haunted by - not just in the South, in America - we are haunted by our unsolved civil rights issues, by horizontal violence between people of different skin color, so we hope that the film will generate discussions particularly around race but also around writing and courage." Author Alice Walker (The Color Purple), The New Yorker critic Hilton Als, biographer Brad Gooch as well as the aforementioned Tommy Lee Jones are among those interviewed in Flannery. Executive producer Chris O'Hare originated the project years ago, collecting interviews with O'Connor's close friend Sally Fitzgerald, who compiled the author's letters after Flannery's death, and editor Robert Giroux, who published O'Connor's books. Actress Mary Steenburgen provides the voice of O'Connor, reading portions of her letters, as well as excerpts from stories. Animation is used to bring the work to life. "What I spent years thinking about was how we can visualize these ideas and these images, with her biography and with her experience," Coffman says, "like going to the Cloisters Museum in New York and finding great paintings that visualize the Medieval grotesque... about this embodied pain and suffering and grotesqueness and she puts it in a context where suddenly it's funny." Bosco adds that with O'Connor there's "a little hook at the end. The hook is, wait a minute, this is not just about humor, she's got something to say. And all of her stories have something to say. She really has kind of a cosmic goal and that goal is to get you in the right relationship to who you are to the universe." Distribution plans for Flannery have not been settled as yet, but the filmmakers say they may have an announcement about that in another month. |

AuthorMatthew Carey is a documentary filmmaker and journalist. His work has appeared on Deadline.com, CNN, CNN.com, TheWrap.com, NBCNews.com and in Documentary magazine. |

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

Proudly powered by Weebly

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

RSS Feed

RSS Feed