|

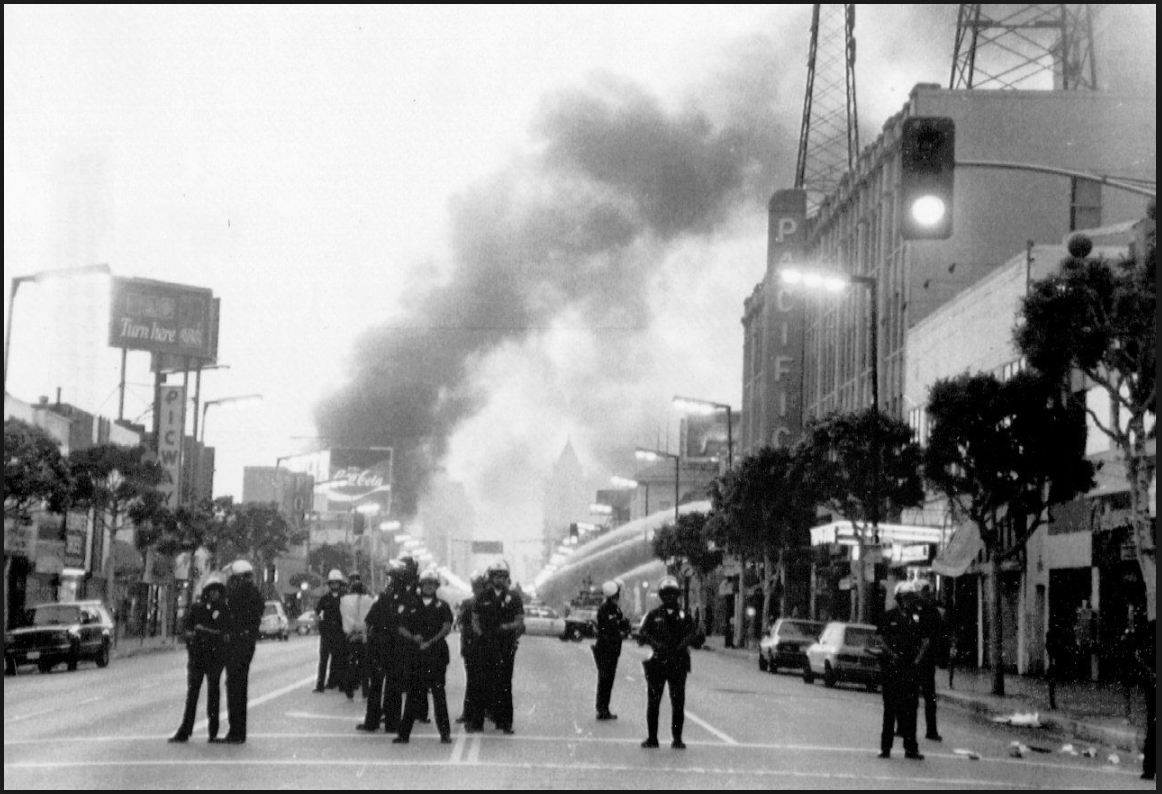

Let It Fall airs tonight on ABC; theatrical version in select cinemas Update Nov. 7, 2017: Let It Fall now streaming on Netflix. Film returns to big screen Nov. 17 at Laemmle Music Hall in Beverly Hills A quarter century has now passed since America's second largest city erupted in what came to be known as the LA Riots. Oscar-winning writer-director-producer John Ridley believes the proper term for what occurred is an uprising. "What we're talking about... is something that was not spontaneous. It wasn't something that just happened in one community or affected one kind of individual," Ridley told Nonfictionfilm.com. Ridley explores the outburst of civil unrest that began on April 29, 1992 and -- just as importantly -- what led up to it in his new documentary Let It Fall: Los Angeles 1982-1992. A two-hour version of the film airs tonight on ABC; a longer theatrical version is playing in limited release. If what happened in Los Angeles 25 years ago was something that built up over time, what's building up right now? The immediate cause of the violence was the surprise acquittal of four white LAPD officers who had been videotaped beating Rodney King with nightsticks after a traffic stop. The intersection of Florence and Normandie avenues in South Central became the flashpoint for six days of cataclysm that resulted in over 50 deaths and a billion dollars in damage. Ridley dials back the story 10 years. He told us he used 1982 as his point of departure because it marked a turning point in tactics used by the LAPD in confrontations with suspects. "1982 was the end of the chokehold era with the Los Angeles Police Department and the introduction of the PR-24 -- the metal baton -- that would obviously be so instrumental with the Rodney King arrest and beating," Ridley said. The LAPD under Chief Daryl Gates didn't give up the chokehold voluntarily. The Police Commission ordered the LAPD to abandon its use after the deaths of more than a dozen suspects who had been put in chokeholds, including James Mincey Jr., a 20-year-old African-American man. In Let It Fall, we not only hear from Mincey's girlfriend who was present for his fatal encounter with police, but also from one of the arresting officers, Det. Robert Simpach. Simpach says he feels no sense of guilt over Mincey's death in 1982, and later in the film he suggests if the officers who beat King could have used the chokehold instead of metal batons, there would have been no need for the ferocious beating. It is these kind of remarkable interviews with key participants and observers that differentiates Ridley's documentary from several others released in time for the 25th anniversary of the LA Riots. "To present people with these stories that they don't know and do it in a way that is highly emotional I think there is an incredible value to that," Ridley stated. Among those interviews is one with Lt. Michael Moulins, the ranking officer on site when the violence surged at Florence and Normandie. It was Moulins who made the fateful decision to withdraw his forces, a move some feel allowed the streets to descend into chaos. "It's his belief that if his officers had remained that deadly force was going to be used against them or that the police themselves would have to use deadly force," Ridley told us. On that day the compassion line was closed. The director and his producing team also secured interviews with several of the men charged in connection with the near fatal beating of Reginald Denny, who was dragged from his truck at Florence and Normandie. Gary Williams, convicted of attempting to rob Denny as he lay in the street, remembers on camera, "I have compassion for anybody... [But] at that time, the compassion line was closed." "It's not even so much about anger and rage but even being able to feel empathy for other individuals, that had shut down within a lot of people," Ridley noted. But that wasn't universal. In one of the film's most emotional moments, Bobby Green, the South Central resident who risked his life to rescue Denny, recalls the divine inspiration he says led him to take action. "These memories are incredibly present for a lot of people. For them these aren't events that happened 25 or even 35 years ago," Ridley said. "They carry these emotions as though these things happened an hour ago, a day ago." The 25th anniversary of the LA Riots inevitably leads to questions about what has changed and what hasn't. Gates was forced to retire shortly after the riots (he died in 2010). Subsequent chiefs embarked on reform of the LAPD's militaristic culture. "I do think there have been changes in the LAPD. Those changes have not come easily and in some cases they did not come rapidly," Ridley commented. What happened in Los Angeles is not exactly the same as what happened in Ferguson or Baltimore or other places. I asked the filmmaker what questions we should be asking ourselves on this quarter-century anniversary.

"If what happened in Los Angeles 25 years ago was something that built up over time, what's building up right now? What communities are being left behind? What individuals are not franchised in a way that many of us are franchised? I think those are the questions we have to ask. As important as it is for us to look back at these events, I think in looking forward we can't assume that the same thing is going to happen the same way with the same demographics, the same individuals, with the same causations. We've got to really ask ourselves what is going on in neighborhoods that are not like mine, with people who are not like me and do they feel the same way I do. And if they don't, why? And what can we do to address it?" Ridley said he is reluctant to draw direct direct parallels between the LA uprising and events in recent years -- the disturbing deaths of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Freddie Gray and other young black men -- that spurred the founding of the Black Lives Matter movement. I observed that these incidents are all part of the terrible legacy of America's race relations. "There is a terrible legacy... We can see very clearly that legacy continues. I do think all of these incidents deserve their own singular examination," Ridley said. "What happened in Los Angeles is not exactly the same as what happened in Ferguson or Baltimore or other places. We should also be aware of this terrible legacy, of how it informs us, how it informs decisions that we make and how we interact. But I don't think there is, nor should there be, an easy mathematical equation in drawing equivalencies very easily between and among these many, many circumstances that we see with frighteningly more regularity. They all deserve a singular examination, because they all deserve singular answers, singular solutions." |

AuthorMatthew Carey is a documentary filmmaker and journalist. His work has appeared on Deadline.com, CNN, CNN.com, TheWrap.com, NBCNews.com and in Documentary magazine. |

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

Proudly powered by Weebly

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

RSS Feed

RSS Feed