|

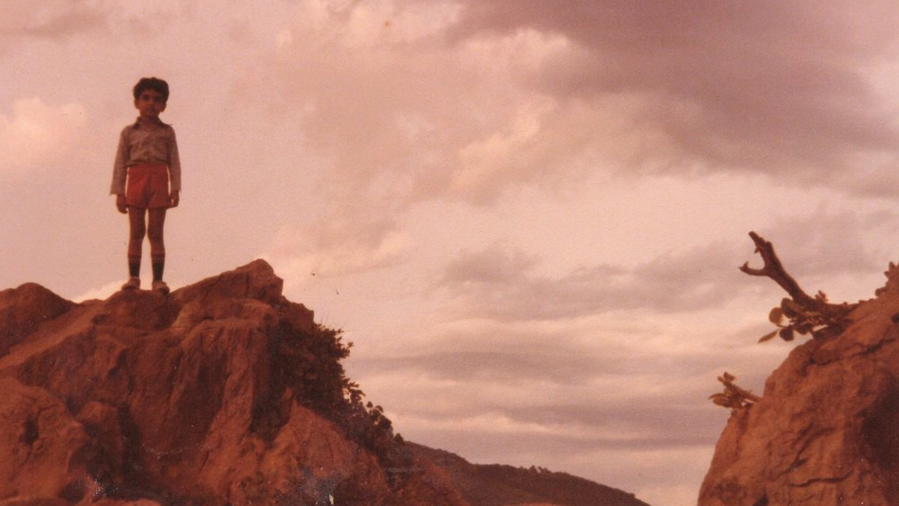

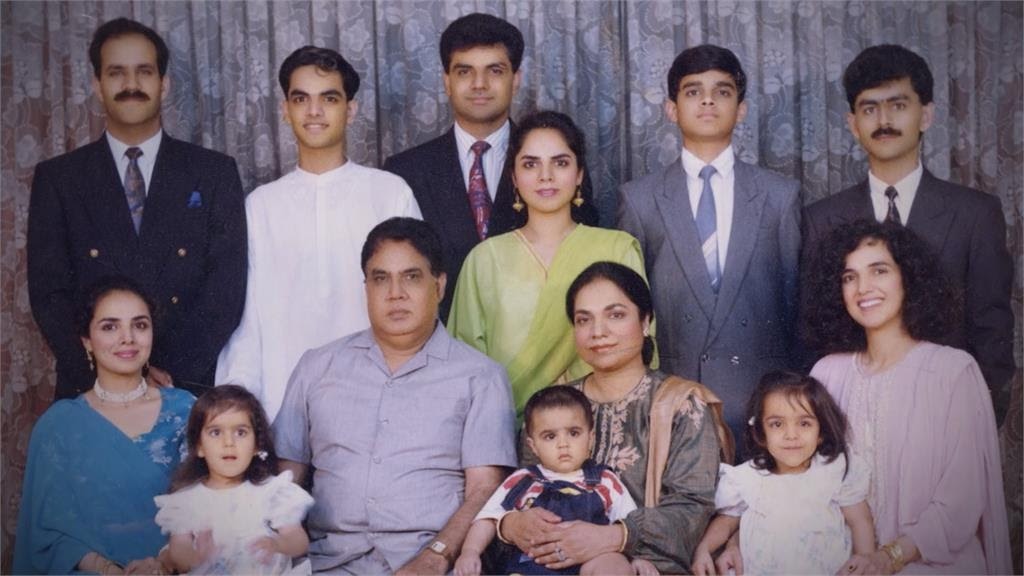

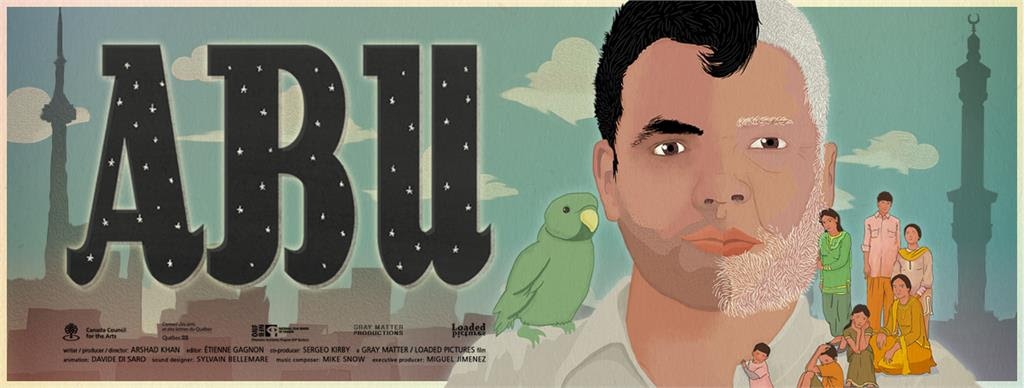

Director Arshad Khan: 'I come from a culture that is very fluid in sexual identity... In the West you have to be defined.' On Father's Day the Los Angeles Film Festival will host the world premiere of a documentary well-suited to the occasion: Abu, by Pakistani-Canadian director Arshad Khan "A father and son search for that elusive place called home," reads the tagline to the film. And indeed the title is the word for father in Urdu, a language spoken widely in Pakistan where Khan spent his early years. It must be said the father-son relationship at the center of Abu is a good deal more complicated than what could be summed up neatly on a Hallmark Father's Day card. I packed a lot in the film. Actually I'm unpacking a lot in the film, I should say. "My father passed away five years ago and that was a very difficult thing for me," Khan told Nonfictionfilm.com a few days before Abu's premiere. "I never thought I would feel this terrible about his loss because I hated him most of my life. It was such a difficult relationship I had with him but I was so devastated after he died that I couldn't understand it. And to help me understand that better I started this film." Part of the conflict between the Khans stemmed from Arshad's sexual orientation which veered more toward the gay end of the spectrum. Both of his parents -- who embraced an ever more conservative version of Islam the older they got -- found it difficult to fully accept their son. The film suggests the elder Khan sought refuge in religion in part because of reverses he suffered in business. His fortunes did not improve when he moved his family to Canada, a dislocation that proved a challenge for Arshad as well. "For a long time I was in between worlds. It was very difficult to have an identity because you're from Pakistan, everyone [in Canada] sees you as a Pakistani. You're always a foreigner," Khan said. "Even if you're born in Canada, you're [seen as] a brown person. People will still ask you, 'Where are you from?' Or, 'Where is your family from?' But that doesn't happen to white Canadians. It's just assumed you're from Canada and that's it." The struggle for identity -- cultural, sexual -- is a central theme in Abu. "Identity is a funny thing and the pressure to come out is also something that I am not entirely sure is the right thing. I think that our society unfortunately is not evolved enough to just let people be, and there needs to be definition imposed on everybody," Khan stated. "I come from a culture that is very fluid in sexual identity. A lot of young men's or young women's experience start with the same sex -- early experiences. And it was understood as kind of normal and then you grow up and then you have a family and you're with the opposite sex. But that idea -- it doesn't exist in the West. In the West you have to be defined. So we see ourselves as very progressive here, but we also are kind of suppressing that kind of natural thing in a certain way." He continued, "The fact of the matter is sexual identity and who you choose to love is a very personal thing and... whether you want to let other people know about it, whether you want to celebrate it or hide it, whatever, it should be your choice, but you shouldn't be persecuted for it. But we're living in times, very seriously dangerous times where there are concentration camps being set up in Chechnya, public floggings happening in Indonesia and ISIS throwing people off buildings for being gay. So we are at a crisis." Khan's brother Mani and two of his sisters -- Asma and Ayesha -- are expected to attend the world premiere on Sunday. But as of now Khan's mother is not listed among the expected guests. "Actually my mother is not okay with [the documentary]. My mother is the antagonist in the film, as you will see. She thought it was [going to be] a film glorifying our father and I told her, 'Mom, our father was nobody. We're nobody.' And she said, 'Well, why don't you just give different names or make like a fictional film?' I was like, 'No, because I need to tell this story,'" Khan recalled. "I said, 'We have so many secrets and lies in our family and it's time that we stop these secrets and lies so that our children in the family and the future generations do not suffer the same way that some of us have had to suffer.' And then she became less paranoid." He added, "What she fears for is my safety, basically, and how people perceive the film. But I've worked very hard to give dignity to my father, to his legacy, and to give dignity to me and my family and to my situation." There are important messages in Abu for an Islamic audience, but equally for those in the West. "For the Western audience this film is a reminder that we come from a very rich tradition and culture and we are very complex human beings. My father was a very complex person and we should not be easily categorized into 'us' and 'them' or good and evil or terrorist or non-terrorist," Khan said. "I think those very diabolical things that we are pushed into and those identities imposed on us and I completely reject them." Khan elaborated on what he hopes people will get from Abu. "I hope the film will be seen by as many parents as possible because I think parents need to watch this film to understand what they put their children through. And then people who want to understand Pakistan or Muslims a bit better, I really think this is a good vehicle for them to see that we are just as messed up as anybody else. We're not particularly more messed up," he said with a laugh. "My reason for making this film is to humanize our people and help a better understanding with the Western Hemisphere, with the Northern Hemisphere, build a better understanding through dialogue and through communication about who we are." Khan praised the LA Film Festival for giving voice to people whose stories are often neglected.

"I'm extremely honored and very, very, very grateful to the LA Film Festival to give so much love to the Abu film project," he said, adding that typically in Western media "there are no voices of people like myself and there's no representation of people who live at intersectionalities of identity, for example. In the representation of people of color there's no nuance, there's no complexity. So that is the reason I went into filmmaking in the first place. I wanted to become a filmmaker to tell stories of these people and humanize them in the eyes of the world, who are absolutely underrepresented or absolutely invisible." |

AuthorMatthew Carey is a documentary filmmaker and journalist. His work has appeared on Deadline.com, CNN, CNN.com, TheWrap.com, NBCNews.com and in Documentary magazine. |

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

Proudly powered by Weebly

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

RSS Feed

RSS Feed