|

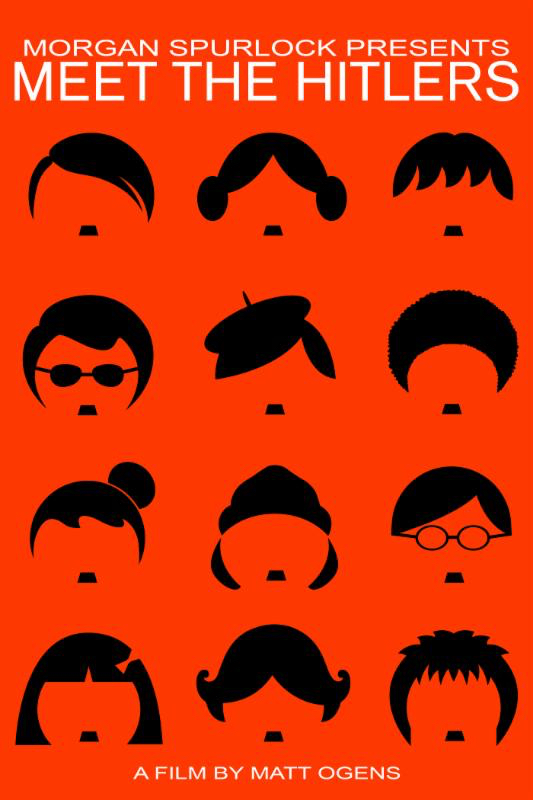

Filmmaker Matt Ogens travels the world to find people bearing the most notorious name in history

Of all the monsters of history -- Stalin, Pol Pot, King Leopold II, Mao Zedong -- one is reviled more than all the rest: Adolph Hitler.

Imagine, then, growing up with the name Hitler. You'd think anyone burdened with it would change it -- whether they were in any way related to Adolph or not. Curiously, some have decided to keep the Hitler name they were born with and it is that group [plus a few others who either adopted the name or deliberately ditched it] who are the subject of the new documentary Meet the Hitlers, directed by Matt Ogens. Morgan Spurlock is the executive producer. I started thinking about the deeper meaning of any of our names. Are they connected to our identity at all? Do our names shape us?

Ogens scoured the country and traveled to Europe in search of Hitlers [and Hittlers]. He also followed the journey of a British journalist who was intent on interviewing the last known descendants of Adolph, who live in the U.S. And he spent time with a neo-Nazi who named his son Adolph Hitler, and his daughter Arian Nation.

Ogens' documentary is now available on iTunes, Amazon Prime, Google Play and on DVD. The film premieres on Showtime Saturday, April 30.

Nonfictionfilm.com spoke with Ogens about his film and the question of what's in a name. [If you want to get a sense of what it's like to have the Hitler name attached to you, the film's website allows you to try it out.]

How did you get interested in this story?

I had a friend in college who ended up marrying a guy by the last name of Hitler and I used to get Christmas cards from them every year saying "Happy holidays from the Hitlers." And of course at first you laugh. You're like, "Oh, that's funny." Then you start thinking, God, I wonder what it's like to have that name. What was it like for her husband who had it [that name] for his whole life? And why he decided not to change it and how it affected his life. I started thinking about the deeper meaning of any of our names. Are they connected to our identity at all? Do our names shape us at all? And certainly with Hitler being the most notorious name in history, or one of them, and [me] being Jewish, I wanted to explore more. I did research, found that there's a lot of Hitlers and they might each have a different story and wouldn't that be interesting if I had a sort of a multi-layered, multi-charactered documentary where I explored that name through different people who might have all experienced it in a different way. The scale of your ambition with the film is impressive because you not only go around the United States but to Europe. You have a significant number of characters in the film. Thank you. That's why it probably took a while to make as well. We knew we wanted to get someone in Germany, for obvious reasons. [Romano Lukas Hitler's] experience with the name is different from someone else's. Every character is in a different town, different city, sometimes a different country.

Correct me if I'm wrong, but Romano Lukas Hitler -- we never learn for certain whether he is in fact related to Adolph Hitler.

I can't really answer for you. I don't want to taint the film with my opinion, so that's for you as an audience member to decide. What do you think, you know what I mean? I don't know any more than you know. One of your characters, Heath Campbell, is a neo-Nazi who renamed his son Adolph Hitler, and his daughter Arian Nation. He lost custody of his kids, either entirely or in part because of the names he gave them. Do you think what happened to him was fair? Again, I don't want to give too much of an opinion as the director of the film. I'd rather the audience do that. I would say this. I wouldn't name my child Adolph Hitler in any circumstances. To me that is a form of abuse of what that child's going to have to live with with that name and it's not his or her choice to have been given that name... But there were other allegations of other things that were [allegedly] happening [in the home]. I don't know all the details.

You have this interesting narrative thread in the film with British author David Gardner, who tries to get the last known blood relatives of Adolph Hitler, brothers living in the U.S., to do an interview with him. You don't reveal their identities. Was that for legal reasons?

That's not my journey and my story. That's Dave Gardner, the journalist's, story. That's his journey. However, you can very quickly online find out where these people [Hitler descendants] live. In the beginning when we were filming, only a few years ago, you couldn't. But you can pretty easily find out their real names. However, I didn't want to be, as a filmmaker, someone that is "outing" someone without their consent so I didn't name their street or their address or showed their images because I didn't feel comfortable with that.

With so many characters in your film, how did you settle on a narrative structure?

That was not easy. There was a lot of footage, a hundred hours of footage and a lot of interviews. And there were some characters that didn't make the cut. That is what documentary filmmaking is. I didn't have a script. I had to find some of it in the edit. I had to find the story. It's like a ball of clay. You've got to slowly make it take shape.

How long do you think it will take for the kind of fearsome quality associated with just invoking the name of Hitler to dissipate? People hopefully won't forget about his crimes, but do you think that name is always going to hold the power it does now?

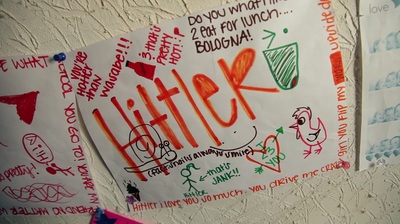

I don't know. I don't know. It would be interesting to ask, let's say, a 12-year-old right now what the name means to them, who Adolph Hitler is to them, see if it has the emotional resonance... I think that name is synonymous, at least Adolph Hitler is synonymous, with evil and you think about that, it's like a brand. It conjures up six million Jews that died, all the things that he did. I think it's going to be around for a while. There is a kind of mystical quality in invoking the name of Hitler -- as if to pronounce the name is to summon the evil. Jim Riswold, the artist and advertising guy [and cancer survivor] in the film, he sums it up. He said, "People talk about cancer in hushed tones. They're afraid to even utter the word cancer. It's just like people are afraid to utter the word Hitler." He's saying if you mock it, you beat it. If you are afraid of it -- Hitler would be upset if he found out people were making fun of him. He wouldn't be upset if they were afraid of him.

In the film Jim Riswold talks about getting grief from some people because he makes Hitler tchotchkes the subject of his artwork. He says he expects you, the filmmaker, will receive similar criticism for doing the documentary Meet the Hitlers. Have you found that to be true?

I haven't found it to be true so far. I mean I'm not a Jewish director. I'm a director who happens to be Jewish and so that's part of the reason that I wanted to explore this. I also don't see anything wrong with it. In some ways what's the difference between this and a documentary on Hitler on the History Channel? Like Jim Riswold said, you have to watch the film or understand his art for it to make sense. If you're just judging it from a distance by a name or an image then you might be missing the message. |

AuthorMatthew Carey is a documentary filmmaker and journalist. His work has appeared on Deadline.com, CNN, CNN.com, TheWrap.com, NBCNews.com and in Documentary magazine. |

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

Proudly powered by Weebly

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

RSS Feed

RSS Feed