|

Doug McGrath film is an 'autobiographical portrait of Mike'

Mike Nichols' death in 2014 deprived the entertainment industry of one of its most accomplished artists -- among the rare talents to capture all the major show business awards: Emmy, Grammy, Oscar and Tony.

Fortunately for posterity, he gave two in-depth interviews just four months before he died, both recorded for the documentary Being Mike Nichols, directed by Doug McGrath. The film is now available on HBO NOW and HBO GO. It next airs on HBO this Thursday [March 3] at 10:30am. I wasn’t surprised by how smart he was because that’s evident in the work. I guess I didn’t expect how warm he was, very warm.

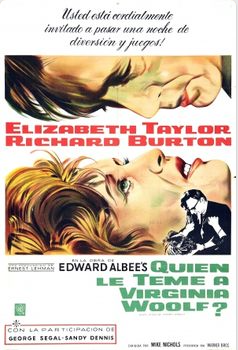

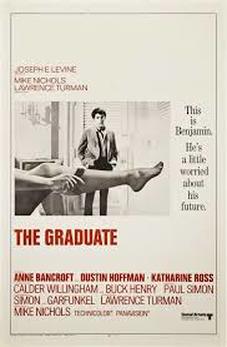

The film is full of fascinating anecdotes about Nichols' career -- from his early improv collaboration with Elaine May, to his Broadway success directing acclaimed productions of Neil Simon and other playwrights, to his exceptional early films -- Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? andThe Graduate.

Being Mike Nichols premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in January, which is where Nonfictionfilm.com caught up with McGrath, whose credits include directing Emma and Infamous and co-writing [along with Woody Allen] Bullets Over Broadway.

How well did you know Nichols before you embarked on the documentary? Doug McGrath: I’d known him a little but not well. But I'd admired him always. I remember the first film I really wanted to see when I was a kid, but my parents wouldn’t let me see, was The Graduate -- considered very racy. "No, you have to wait," which of course made me want to see it more. And Mike was just what you’d dream of, and this is not always true. Many times if you meet people you’ve admired for a long time sometimes it’s a disappointment because either they are not what you thought [they'd be] or they’re not very nice or they don’t live up to what your expectation is. But Mike is just what you would think. When you hear that name “Mike Nichols” you think of a certain kind of intelligence and a certain kind of wit, a certain kind of sophistication, and he was all those things. He was very charming, He had a quick, quick mind. I mean you can’t improvise the way he did with Elaine [May] all those years and not have a rapid style of thinking... I wasn’t surprised by how smart he was because that’s evident in the work. I guess I didn’t expect how warm he was, very warm.

In taking on this project you were directing a film about a film director, which I would imagine might be intimidating.

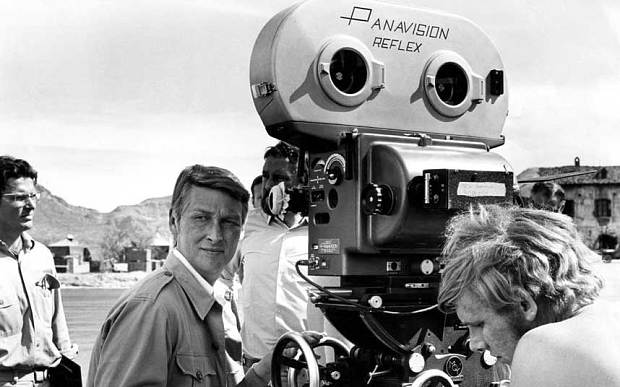

It was kind of a thrill because, you know, we were shooting seated interviews. I would say, “Here, come, let’s look at this together, I want you to be happy." Because it’s not an investigative portrait of Mike. In many ways it really was kind of like an autobiographical portrait of Mike in which he leads us. He’s sort of like our guide. And we’d look at the shot together and he’d say: ”Oh, maybe this or that." He was entirely collaborative. There are only three types of scenes: negotiations, seductions and fights... All scenes come into one of those categories.

He was 82 when you filmed the interviews. He was so vital and his recall of things was astonishing.

His memory of events 60 years ago –with Elaine [May] coming out of college, starting with the Compass Players, the early work with Neil Simon and then of course the films. The mind, the memory, is not only complete but the details –- that story he tells about Richard Burton, for instance. where Burton has to figure out how he’s going to cry in the scene [from Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?] -- that was all as vivid and alive to him as if it had just happened.

There are some amazing stories in the film about Nichols directing his first movie, Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? He wanted to shoot it in black and white because he felt the heavy makeup Elizabeth Taylor needed to wear to age herself [she was 32 but played a character who was 56] wouldn't work in color.

To get the studio to allow him to do it in black and white, to get the right DP [director of photography], everything was a struggle that he had to master in some way. But what our film shows is that if you stick with it and if you master it that’s the only way you can get a great film. If you’re just like, "All right, they want us to do it in color, we’ll do it in color,” well Virginia Woolf wouldn’t be that film in color. Let’s not say it would be bad, but it wouldn’t be that film which is so vivid.

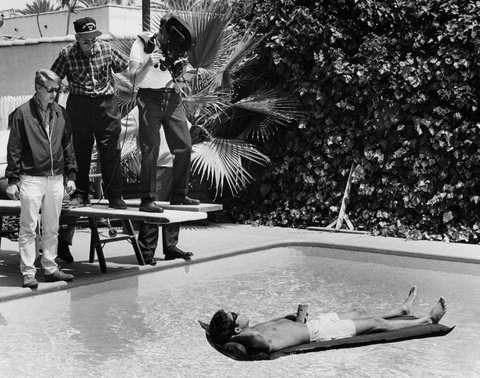

There are also great stories of the making of The Graduate, his second film. How he came to use Simon and Garfunkel music in it -- and how Simon changed a song he was working on -- "Here's to You, Mrs. Roosevelt" -- to "Here's to You, Mrs. Robinson" for the film.

Mike told me he thought it was his best film, and I can see why. I think it’s the most complete and the most successful of all the things [he did], and the most original.. I have to say for my generation, I think The Graduate was the most influential film. It’s The Catcher in the Rye of films for my generation. It’s the film where you think, “Oh my god, this film is talking to me in a way that no other film is talking to me.” They get better in the bath overnight.

The Graduate is such an accomplishment. All the choices are so extraordinarily apt for the material, so correct for what that mood was –- Benjamin’s mood was [Benjamin Braddock, played by Dustin Hoffman]. You always want your film, in all its aspects, to represent your main characters –- what he or she is feeling. It has to support and deliver that to the audience. And The Graduate does it at every level, in the production design, in the photography... So to me that’s the film that stands out above them all.

Did Nichols know he was ill when you were doing the interviews for the film?

I don’t think so. We were very friendly, he didn’t ever talk to me about that nor did he talk to Frank Rich – my co-executive producer – or Jack O’Brien [who conducted the interviews] who was his pal. He died four months later, but what he died from was a sudden heart attack. He had just had his pacemaker changed, he’d come home from the operation, he was feeling fine, he was sitting around the house and he said, “You know what, I feel a little faint,” and then he stood up and then just collapsed. So it wasn’t the result of an illness, but he was clearly not in the best of health.

He didn’t tell us this but it seems obvious when you look at all the footage [we shot] that what he wanted to talk about was the early work. You know, as people get older their mind does tend to turn back. And he also told me he thought the early work was his best work. He wasn’t saying he hadn’t done good work since then but he thought this was his best work. So I've often wondered, maybe he wanted to get down for the record –- he was a smart man, he knew he wasn’t going to live 30 more years –- so he thought, “Maybe I need to get these thoughts down about that material that I think best represents me.”

|

AuthorMatthew Carey is a documentary filmmaker and journalist. His work has appeared on Deadline.com, CNN, CNN.com, TheWrap.com, NBCNews.com and in Documentary magazine. |

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

Proudly powered by Weebly

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

RSS Feed

RSS Feed