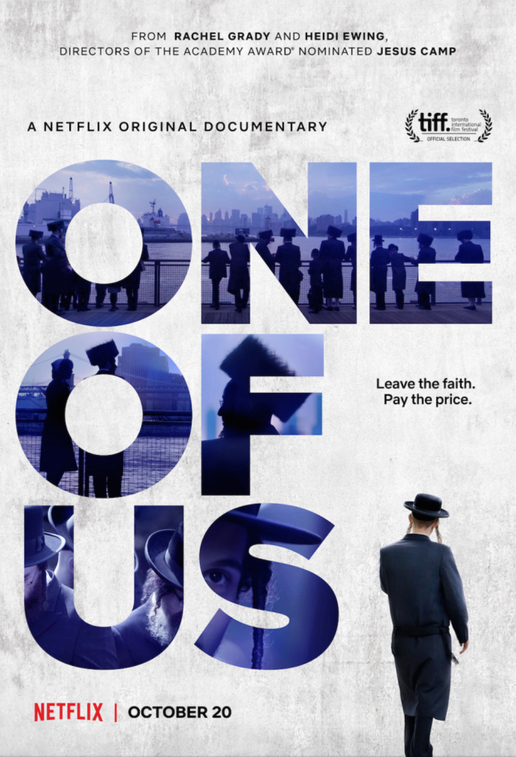

New on Netflix: 'One of Us' a rare look at renegades in New York's tight-knit Hasidic community10/24/2017

Documentary from Heidi Ewing and Rachel Grady follows three people who wanted out: 'It is nearly impossible to exit... and start over in the secular world'

Update: One of Us has been shortlisted for the Oscars

Filmmakers Heidi Ewing and Rachel Grady have spent much of their careers documenting the varieties of religious experience (to borrow the title of the William James classic).

They earned an Oscar nomination for their 2006 film Jesus Camp, about a Christian camp in North Dakota where children were taught to sacrifice their lives for God if necessary. "We even dipped a toe in the Islamic community," Ewing told Nonfictionfilm.com. "We made a film called The Education of Mohammad Hussein, about a madrassa in Detroit. So we really have run the gamut." Their latest film, One of Us -- now streaming on Netflix -- explores New York's Hasidic community, a religious sect that exercises strict control over its flock. You are taught not to make eye contact, not to interact with people outside your community.

"You are in New York City [but] you stay on your block, you stay in your neighborhood," Ewing told us. "You are taught not to make eye contact, not to interact with people outside your community. Plus, everything that you need done for you is done by your neighbors, is done within the community. Your life revolves around the Jewish holidays, your school, your social life."

One of Us focuses on three people who became, in effect, exiles from the Hasidic community: Luzer, a man who dreamed of pursuing an acting career; Ari, a young man who felt the urge to explore the outside world, and Etty, a young mother of seven who sought to flee an abusive husband.

The filmmakers found their characters through an organization in New York called Footsteps, which provides counseling and other services to Hasidic people who decide to leave the ultra-orthodox fold.

"Thanks to Footsteps, former ultra-Orthodox Jews have a safe, supportive, and flourishing community to turn to as they work to define their own identities, build new connections, and lead productive lives on their own terms," the organization says on its website. It is nearly impossible to exit the Hasidic community and start over in the secular world.

But the documentary explores just how difficult it can be to quit the fold.

"It is nearly impossible to exit the Hasidic community and start over in the secular world -- and some would say that's by design," Ewing said. "The community does not take kindly to members leaving." She added, "The Hasidic community has created sort of a parallel system -- they have their own school system, the Yeshiva system, private, that most kids go to. There's very little English being taught in a lot of the Satmar sect schools, for example. There's a lot of Torah and Talmudic studies. And the kids are not at grade level whatsoever, compared to even a public school in New York... Some of the girls get up to maybe a sixth grade education. So right there you've got a problem with leaving."

Anyone who separates from the faith community is shunned, the filmmakers said, cut off from family and an entire way of life.

"You get everything if you're with them. You get help... you get financial protection, you get emotional protection," Grady told Nonfictionfilm.com. "It's all-encompassing and it's very comforting, but it's conditional. And if you deviate even a fraction from that condition, you're gone." In the case of the young woman Etty, leaving her husband ignited a custody battle over her seven kids. "Having children and trying to leave the community with your children is a red line that cannot be crossed," Grady stated. "Someone in our film says, the kids are considered property of the community. So you can't take their property and they'd rather push you out and never see you again -- literally 'ghost' you -- than let you take the kids, which in their opinion are part of God's design of why [the Hasidic faithful] exist." The film shows how the Hasidic community has made strategic use of the "status quo" argument in such legal disputes, arguing that children must continue to be raised in the faith -- even if that means being denied a relationship with their mother, as was the case with Etty. "Etty was willing to keep her children in the Hasidic schools and to keep kosher and to keep the shabbas all of the main tenets. She was very willing to do that, but that wasn't enough," Ewing said. "Because the Hasidic community believes that even if in your mind you're quietly having doubts of any kind you're somehow going to transmit this to the children and make them goyish and make them secular and outcasts in their own community."

The filmmakers' sympathies are with the three people who chose a life of greater freedom -- and greater uncertainty -- over unquestioned fealty to the community creed.

"The people that we encountered at Footsteps are really a self-selected group that, by hell or high water, felt like they didn't fit, they couldn't stay. And they're willing to sort of take this leap off the cliff and face the consequences, which makes them a very intense group of people and a real brave bunch." Ewing said. The title -- One of Us -- suggests the struggle for identity that's at the heart of the film. Secular people, surely, want to claim these brave seekers as "one of us." That bias in favor of personal liberty runs completely counter to the Hasidic faith, where the community maintains strict standards about who qualifies as "one of us." As Ewing put it, "Are you one of us that have left or are you one of us that's God's people? They are being claimed by different groups."

One of Us made its debut on Netflix on Friday, exposing the story of Etty, Ari and Luzer to a much wider audience. Where religion is concerned, of course, strong reactions may be expected.

"We're worried more for our subjects than for ourselves. Hopefully no one is hurt during this," Grady told us. "And I suppose if we started thinking about bad things happening to us we could get nice and nervous. But someone like Ari -- he's half in, half out [of the Hasidic faith]. And I want him to get something positive out of this experience." "They're going to get a lot of love from all over the world and they're going to get limited hate from their own community," Ewing predicted. "So there's going to be a lot more support than there is negativity -- for sure, a hundred percent... We've definitely told them to shore up their social media, turn off comments perhaps... I don't think they grasp that. Ari is kind of like, 'I want to see what comes at me.' I'm like, 'Oh, lord.' Luzer is just like, 'I'm looking for parts, I'm looking for roles. I'm ready to work.' So we're not worried about him."

|

AuthorMatthew Carey is a documentary filmmaker and journalist. His work has appeared on Deadline.com, CNN, CNN.com, TheWrap.com, NBCNews.com and in Documentary magazine. |

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

Proudly powered by Weebly

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

RSS Feed

RSS Feed