|

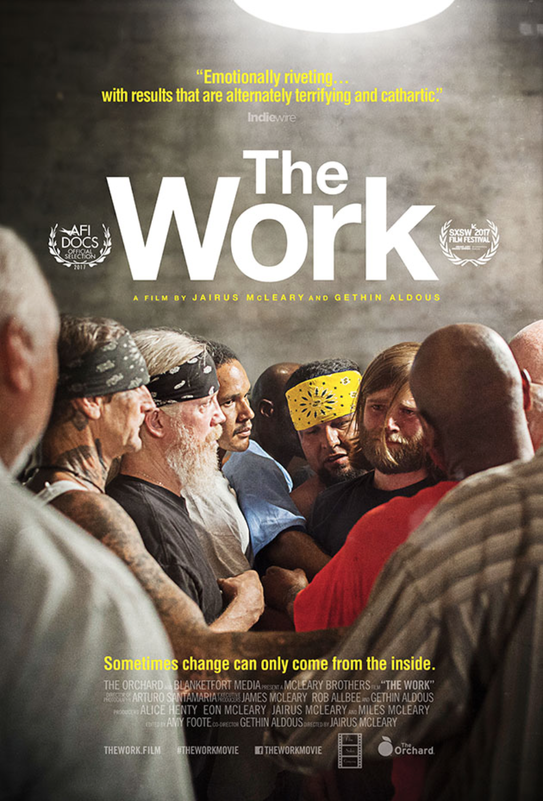

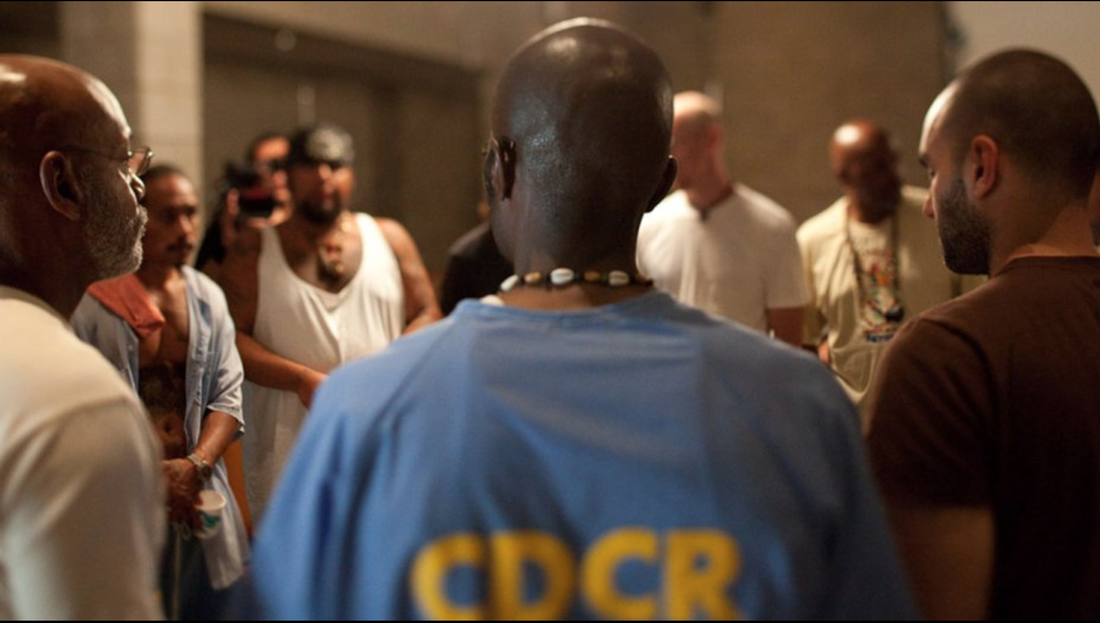

Powerful group therapy encounter -- for prisoners and men from the outside -- revealed in SXSW-winning documentary A log overdue discussion has been taking place in this country about toxic masculinity -- the culturally-embedded phenomenon responsible for so many mass shooting cases, emotional and physical brutality, sexual harassment and debasement of women, to name but some of its ugly manifestations. "Feral masculinity affirms itself every day through violence and domination," as Renée Graham wrote in a recent opinion piece for the Boston Globe. "It is a detriment to social and political progress, our mental health, and physical safety. The deleterious result is a nation under siege by those compelled to affirm their power by any means necessary." For those looking for ways to counteract toxic masculinity, the new documentary The Work offers some insights -- from inside the walls of California's Folsom Prison. It felt like I was coming face to face with a dragon. The film directed by Jairus McLeary and co-directed by Gethin Aldous puts viewers right in the middle of a pulse-poundingly intense four-day group therapy session involving "level four" (i.e. serious) convicts and members of the public who volunteer to participate. "It's a rehabilitative program with the goal of just making things safer inside the prison but also making better, safer men who come out of the prison," McLeary told Nonfictionfilm.com during a conversation in Los Angeles, where he was joined by his brothers Eon and Miles, who produced the film, and their father James, executive producer. The Work, winner of the top prize for documentary at SXSW, is now playing in New York, Los Angeles and other cities, and expands to more locations this Friday (details here). Jairus McLeary first witnessed one of these group therapy sessions about 15 years ago. The opportunity came about because his father, a clinical psychologist and CEO of the Inside Circle Foundation, played a central role in running the program. The foundation describes its mission as creating "environments in which prisoners can work and explore the issues in their lives that have prevented them from living up to their full potential as human beings." The environment where the therapy sessions take place is deep within Folsom. "All it is is a cement room with no windows, super high ceilings. It's sort of in the bowels of the prison," said Eon. "There's a stillness to it... It's like the most intimate environment where you can really feel where other guys are. But it's also explosive." Explosive because the prisoners are being challenged to show vulnerability, to expose the emotional pain underneath their hardened, tattooed exteriors. "Anger -- and the extreme of anger is rage -- is a cap for all the other emotions," James observed. "And as men -- especially men that grow up in pretty volatile and dangerous neighborhoods, they don't get to express but one emotion. You can't be happy and you can't be sad. And you can't show your fear, so you can only express this anger. So that's the emotion they've developed and matured for so many years." The film shows what can happen when the hard shell cracks -- men who ordinarily project intimidation falling into tears. In some cases, the men howl in what seems like a swirl of rage and primal grief. "Sounds like a medieval torture chamber sometimes," Miles said. The prisoners, who have been incarcerated for victimizing others in one way or another, find words to share the psychic injuries that would turn them into violent men. "I'm not trying to let anyone off the hook for the terrible things they've done -- and that's not what they want either -- but they're graphically horrific the sort of childhood stories they tell me," Eon told us. "There's just no way you can survive that intact. They have an awareness about that." The benefit of the group therapy for inmates is clear, but why would men from the outside wish to take part in what can be a volatile and frightening process? "They sense a call. 'This is something I should be doing,'" James said. "And then there's the vetting process -- 'Are you willing to be as authentic as you possibly can be?' Because there is no profile for anybody to [go] in there, except you just have to be authentic. Once the call happens, the gravity of exposing yourself down to transparency is so dense that it just happens at that point." I think it touches everybody, whether they want to be touched or not In that dramatic environment, men from outside the prison reconnect with emotional damage they too have suffered. For one man in the film, Chris, it was a long-buried sense of never winning his father's approval. "The abuse or trauma or slight to the ego that anybody feels is pretty relative... There's no judgment about how deep the pain goes based on whatever happened to you," James observed. "It doesn't matter whether you're inside or you're outside -- there's a commonality and a universality about what hurts me and then what do I do with that hurt. It's the 'what I do with that hurt' that's kind of a learning that people pick up and go, 'Oh wow, that's insightful. I don't want to do that.' Or, 'That definitely relates to what I do.' So there's a learning process, that's a soul learning, if you will." "When males start feeling their emotions really what's happening is they're rebalancing themselves," Miles said. "It's like they're integrating different parts of themselves instead of just this one archetype of the manly men that we've seen -- at least I've seen -- throughout the media since I was a child. There's more to being an adult male then just that archetype. There is certainly a use for that archetype but that's not all that there is. And so I think when people do the work they start to expand their sense of masculinity and in this day and age I think it's imperative this needs to happen, at least in this country. Now is the time for this." Viewers may find The Work cathartic, though some may experience it differently. "I like to go into the screenings and I sit through the whole movie and watch the audience," James told us. "There will be men that just can't sit still in their seat. They are so bothered by what's going on and so repressed and trying not to be bothered that a lot of times they have to get up and leave the [theater] under the pretense of going to the bathroom or something... I think it touches everybody, whether they wanted to be touched or not." The group therapy program has made a significant impact on reducing violence within the prisons where it has been implemented. Another powerful indication of its value comes from data on rates of recidivism. No inmate paroled after taking part in the program has gone back to prison.

"The rate of recidivism in the state of California is 70 to 73-percent, somewhere in there," Jairus said. "You re-offend and you go right back [to prison]. And for this program it's zero." "The singular most important reason the program has had successes in prison is that it is strictly voluntary," the Inside Circle Foundation website notes. "The inmate gains nothing in system credentials by participating. As a result, the only people who get involved are those individuals who at some level are already serious about trying to see if there is any part of their lives that are salvageable. Many of the participants are lifers, some with no chance of ever getting paroled. They understand that there is only one world left for them to explore, the one inside of themselves." |

AuthorMatthew Carey is a documentary filmmaker and journalist. His work has appeared on Deadline.com, CNN, CNN.com, TheWrap.com, NBCNews.com and in Documentary magazine. |

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

Proudly powered by Weebly

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

RSS Feed

RSS Feed