|

The director talks with Nonfictionfilm.com about his cinematic approach to storytelling: 'I want the images to talk on their own'

The migrant crisis in the Mediterranean Sea has drawn the attention of countless news organizations around the world, and numerous documentary filmmakers. Recently, the short doc 4.1 Miles -- about the crisis and its impact on the Greek Island of Lesbos -- won a Student Academy Award. The film was nominated this week for a prestigious IDA Award.

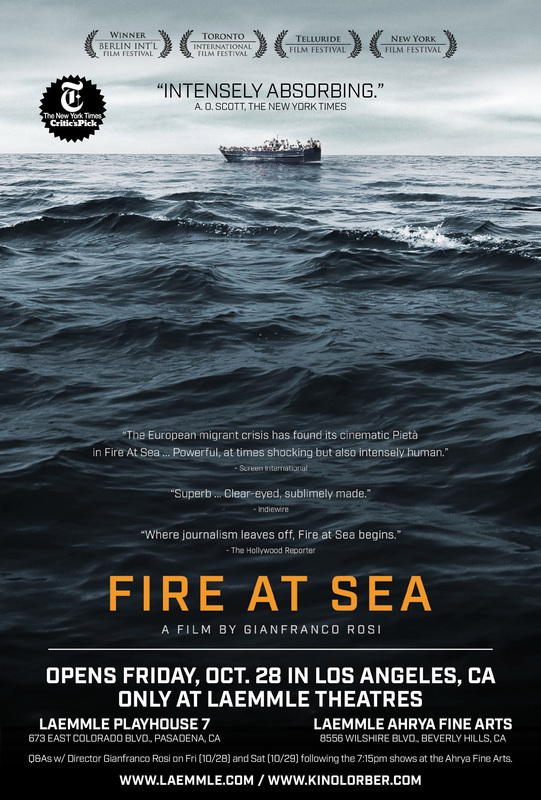

The IDA Awards recognized another film that touches on the migrant crisis -- Fire at Sea [Fuocoammare] by the Italian director Gianfranco Rosi. It will compete in the Best Feature Documentary race, and is already assured of winning Best Cinematography from the IDA. On Thursday, Fire at Sea was nominated for the inaugural Critics' Choice Documentary Awards. This follows its win at the Berlinale last February -- the first documentary to claim the Golden Bear. And as if that weren't enough, the film has also been named Italy's official entry for the Oscars in the Best Foreign Language Film category. I don't ask any questions to the people I have in front of the camera. I let them live their own moments, their own life.

Yet to describe Fire at Sea as a film about the migrant crisis would be misleading. Yes, the tragedy at sea is partly the focus of the documentary. But it could just as accurately be described as a character study of two residents of the island of Lampedusa, where thousands of migrants have come ashore in recent months, and thousands more have perished en route.

Fire at Sea is in fact a difficult film to characterize, which is a tribute to the wholly original approach Rosi takes to his subject. It is an experience to see the film, one that can't really (and shouldn't) be reduced to a paragraph or two. With his film Rosi is pointing documentary film in a new direction, one that remains within the realm of nonfiction, but where visual imagery and metaphor are the driving force.

SHARE THIS:

Fire at Sea is now playing in New York at the Lincoln Plaza Cinema and the IFC Center. It just finished a run in Los Angeles, which will qualify it for Oscar consideration.

Nonfictionfilm.com spoke with Rosi in LA about his approach to Fuocoammare in particular and filmmaking in general. Nonfictionfilm.com: Most directors would take on this subject matter in a very explanatory fashion -- "Here's what's going on with the migrant crisis, this is the plight of the those fleeing North Africa and the Middle East." But your approach is far more elliptical. Gianfranco Rosi: It's a different approach to storytelling. It's about closing the door instead of opening up the door of information, you know. I always say that the more you open that door the more difficult it is to make sense [of things]... Journalism is reduction; you're given this meaning, "Well, this is precisely what happened here." I have a feeling that you're never going to come out of that. Once you’re in the that [mode of] giving information, then you have to use so many elements like voiceover which is no longer cinema anymore. We live in a world with so much information around us. What' s the point of giving more information with a documentary? I like to reach the more emotional element to create a universal language somehow, more close to poetry than to an essay.

GR: I don't ask any questions to the people I have in front of the camera. I let them live their own moments, their own life. And then from there the life is so strong, the reality is so strong, that it becomes magically something else... Sometime people go to see this film and they don't know it's a documentary -- it happened to me many times -- that people think it was a fiction. It's important that people go to see this film knowing that it's a documentary and then see that it is a different approach of telling story in a documentary.

Reality has to talk to me, not me to the reality.

NFF: Probably a lot of people go into the film thinking it's a movie about the migrant crisis, and that's certainly part of it. But you have these different worlds running in parallel --

GR: You have three separate worlds. You have the migrants arriving in Lampedusa, you have the story of the Lampedusan people, and you have the story of a rescue of a boat that looks like a phantom with no people. It looks like this empty ship that goes through a hypothetical rescue and then encounters death in the middle of the ocean, in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea at the border of Europe. And then outside the frame there's a fourth story -- and it's politics. That is pumping in constantly in the film... There's no thesis in my film, there's no statement. So it leaves a totally free interpretation of the people that watch the film. That was my challenge, to use documentary in an experimental way, in a way, to create always a new language, every film. Reality has to talk to me, not me to the reality. And I have to open myself to the unknown because it's like being in a labyrinth and finding a way out. I put myself in the middle of this incredible labyrinth and then have to be able to find my way out of that and that takes a long time. It's a long process. My biggest investment is time.

NFF: When I heard you speak in Cannes I was surprised to learn that when you first went to Lampedusa you didn't have a camera with you. You aren't the type to begin shooting immediately.

GR: For me it's always difficult to put a camera because the camera suddenly changes everything. First for me it's important to create a relationship. It's important to find the people that I want to be with and once I find these people that I want to start my journey with then it's going to be the group I take to the end. I don't betray them. I don't say, "He doesn't work. He's out of my film." But then what I do is I create a void around them. [In my film] it looks like there's only six people on Lampedusa. You don't see anybody. But then every person has to embody this story that we don't see. A good frame in a film is like when you include things also you don't see. So this story here has to also embrace what you don't see. It became this magic moment, completely.

NFF: Your main character is Samuele, this 12-year-old boy. And then your supporting character, you might say, is Dr. Bartolo, the only doctor on the island. Maybe it's my perspective as an American but it seems like there would be a lot of effort involved in arranging to shoot so much with a kid.

GR: Of course I had to get permission from the parents, but then there was no problem. I was not working every day with him. Sometimes two or three weeks we wouldn't do anything. It took more than a year somehow of collecting these moments. So I was not like obsessively working with him. It was more like [filming] a playful moment or like an appointment that was important in his own life. When he did the eye visit with the doctor. When he had this anxiety attack [which brought him to Dr. Bartolo]. I went into the little office and then I switched on the camera and then they [Samuele and Dr. Bartolo] met and that scene came out completely in a very spontaneous way. Because they never met each other before. Dr. Bortolo didn't know him. It became this magic moment, completely, where Samuele tries to explain his anxiety which at that point in the film is our anxiety. When he has nausea it's our nausea. When he has the lazy eye it's our lazy eye.

NFF: Samuel is such a compelling character. He's like an old soul.

GR: He is an old soul. NFF: He's like a little man. GR: He is a little boy with a man head. With an old man head. He's like the Woody Allen of Lampedusa [laughs]. With the humor. NFF: In a way it felt like Lampedusa is almost unaffected by the migrant crisis. GR: Well, it isn't. Because since Lampedusa was militarized -- it is a militarized zone -- there is not anymore any encounter between the people of the island and the migrants arriving there. So these two worlds are very separate. Lampedusa becomes this microcosm of what Europe is, of what the world is. It's a very small island... Even in a place so small these two worlds, they never really interact. They are separate. The link [bridging] the two worlds is Dr. Bartolo. Dr. Bartolo is the voice of awareness in a way in the film. In a way he is the voice of the subconsciousness. [With Samuele] The harshness of growing for a kid, it's like a coming of age situation and that's what I felt very strongly when I was filming him. So for me it's important to always create this very strong almost character study to see what the truth is. For me the truth in documentary is like the truth of the person that I'm filming. Samuele has to be a very strong, intimate portrait of who Samuele is. That for me is what the truth is.

GR: Between the Bartolo character and Samuele then we are able to face death in the film, because without these two characters it would have been completely gratuitous to encounter death, that scene of death [on the migrant boat].

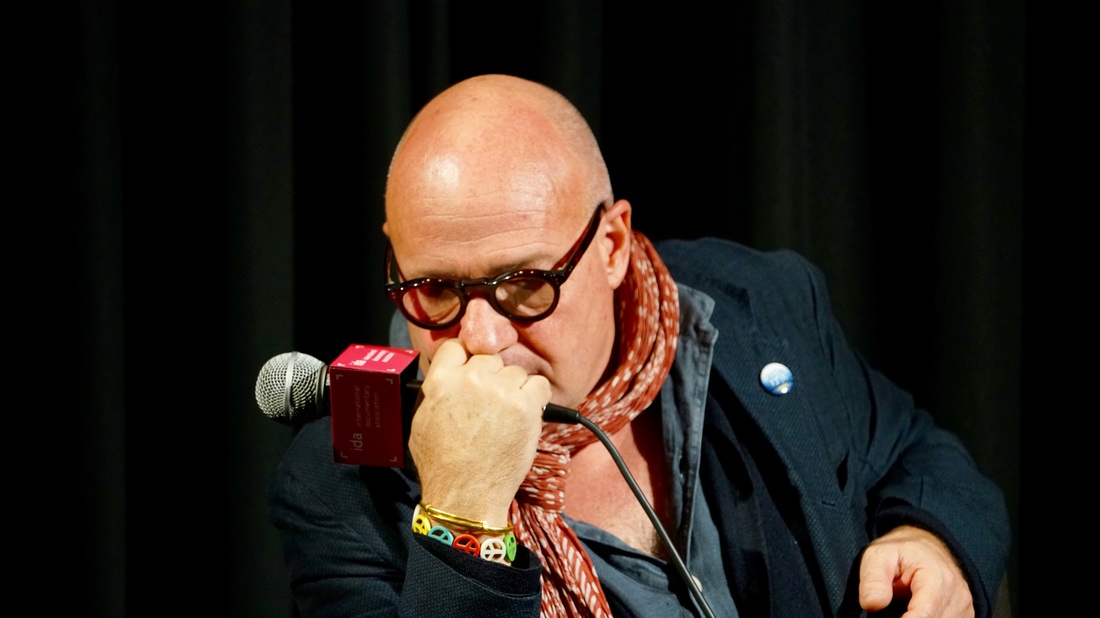

NFF: After the IDA screening of your film you spoke of how excruciating it was to film that scene on the boat where so many migrants died below deck. GR: Filming death is something you don't want to do... This is a tragedy -- we are living history in this moment. I think after the Holocaust it's one of the biggest tragedies Europe is living. We are talking about thousands and thousands of dead, people encountering death on the border of Europe. I had a second to decide should I show this or not [the bodies below the deck]? The commandant of the ship told me, "You have to go there. It's your duty to film that. It's like a gas chamber, that's how these people die, [from] the fumes of the engine. And it's your duty to show this to the world." And once I did that something broke inside of me. And it became the end of the film. I still was not sure if I had enough material but emotionally this time I was not able to put the camera on something else. I had to start editing. And that's when I told my editor I want to include this scene and the whole film we have to conquer this scene. We have to somehow gain that scene. The whole film [must] somehow build to the emotion of that scene and to go out of that scene and to give a dignity to that death and to the people that I was engaged in making the film with.

NFF: You grew up in Eritrea. Do you think that experience gave you a particular insight or perspective on the migrant crisis? You've lived on both sides of the Mediterranean.

GR: It's very hard to detect what forms you as an individual. My life was always a wanderer. I always moved from one place to another place. I was in Ethiopia. I was in Eritrea. Then I went to Italy, then I went to Istanbul, then I went to Libya, then I went back to Italy. I went to the States, to New York I always have to adapt myself to completely different places. And that's for me what is important. When you adapt yourself you have to give up somehow your own identity and somehow understand things that you are interacting with. So I think more than that it's more like my nomadic life that somehow allowed me [insight]. Every place I go I become part of that place. But being part of that place it means I have to be there and give up who I am somehow in order to understand what's going on there. So this is for me the duty of every artist, when you work on something, completely always canceling your past and starting from scratch always every time. I start interacting with things like everything is new and everything's open to a new experience.

Two images of Gianfranco Rosi from a Q&A held after the IDA screening of Fire at Sea in Los Angeles. October 25, 2016. Photos by Matt Carey for Nonfictionfilm.com

|

AuthorMatthew Carey is a documentary filmmaker and journalist. His work has appeared on Deadline.com, CNN, CNN.com, TheWrap.com, NBCNews.com and in Documentary magazine. |

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

Proudly powered by Weebly

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

RSS Feed

RSS Feed