|

Film shows how Magnus Carlsen rose from awkward child to heights of game that stands as 'metaphor for intellect'

Update: Carlsen wins third straight World Chess Championship title, in 'rapid playoff'

When you can beat Bill Gates at chess in 11 seconds, you're a special kind of smart.

But dispatching Gates in a flash is the least of Magnus Carlsen's accomplishments. At age 25 -- Magnus turns 26 on Wednesday -- he already has become the highest-ranked player in the history of chess, with a mind capable of processing an astonishing quantity of possible moves in the most complex game ever created. He can see 100 moves in advance, he confesses, if given the time. The extent of his brilliance is captured in the new documentary Magnus, directed by Benjamin Ree and produced by Sigurd Mikal Karoliussen, who like Carlsen hail from Norway. A little boy from Norway becomes the best, the highest-rated in history at that sport. Against all odds. I think that's a story worth telling.

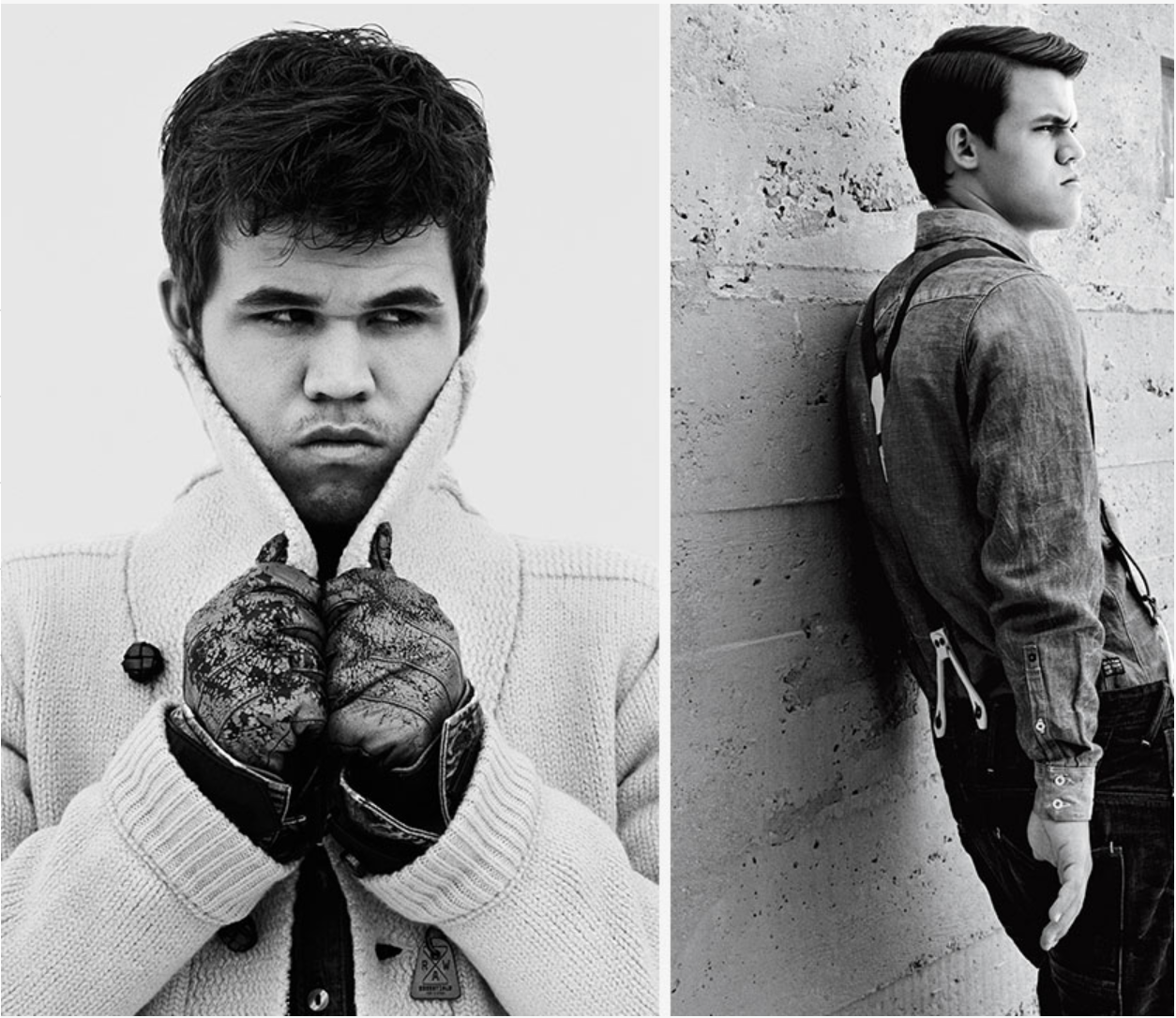

Carlsen's success has made him immensely popular in his home country and famous around the world. He's starred in commercials for Porsche and the international fashion brand G-Star Raw. Carlsen is currently defending his World Chess Championship title in New York City, a media event that has attracted global attention.

Update: Carlsen won the championship Wednesday night in a thrilling 'speed playoff' against his Russian opponent, Sergey Karjakin. Lest anyone think Carlsen's journey to the top of the chess world was easy, the documentary dispels that. His childhood was characterized by bullying from classmates and a deep feeling of isolation. It was not easy for him to find his place in the world.

SHARE THIS:

Magnus for me he is a modern icon for creative thinking. For continuing to be playful.

Carlsen's parents, Henrik and Sigrun, dared to let their son explore chess on his own terms as a boy, rather than requiring him to study the game, as experts -- including the great Garry Kasparov -- insisted was essential to his advancement (Kasparov once compared the young Magnus to an apple, which he said the parents were allowing to rot to the core).

In the end, his parents' instincts would be validated as Magnus developed a creative and intuitive style of play that would eventually surpass anyone else's. As Ree puts it, "Magnus has revolutionized chess. He brings the human element back to the chess game." Magnus is now playing in Los Angeles, at the Laemmle Music Hall in Beverly Hills. It became available on VOD platforms including iTunes on Friday. Nonfictionfilm.com spoke with director Ree and producer Karoliussen over"Impossible Burgers" at Crossroads Kitchen on Melrose Avenue, shortly before the film's debut in LA. What do you think the film can teach us about parenting? That's one of the touching aspects of it. Benjamin Ree: I think that what's really incredible about this story is that they [Henrik and Sigrun] had a child who was so different than other children. He was lost in thought. He had really special traits. And as Henrik says in the film they were worried about his relative development. I think that many parents would have looked at this as a big obstacle, as a huge disadvantage. But Magnus' parents saw the opportunity. And they focused on what kind of perks this can give this life... Not force him to do anything but support him. There is wonderful footage in the film of the young Magnus, from before he even started playing chess at age five. BR: I researched a long time to find that footage and it was Magnus' aunt that filmed this. That was when Magnus was 4-6. You can just imagine the film without that footage. We wouldn't have a feature length documentary. When he was 13 it was one of the producers [of the documentary] that started to film Magnus -- back in 2004.

In the early part of the film we hear a lot from Magnus' father, not so much from Magnus reflecting back.

BR: It's more interesting to hear a father's point of view of a son who is a prodigy and special growing up than Magnus himself talking about when he was a child. Henrik has a great voice as well. It's kind of relaxed but there's a lot of emotions in the voice. You show some phenomenal displays of his abilities at chess, including that scene at Harvard. BR: He played blindfolded against 10 chess players, all lawyers. After the game one of the 10 chess lawyers came up to him and asked, "Do you remember my game?" And then Magnus recited all of the moves from that game... I was there filming that scene, that day he won all the games against all the lawyers. People were just amazed. I definitely got the sense that there's an obsessional quality that Magnus doesn't really have any control over. His mind is spinning, doing calculations constantly. It doesn't seem to be something he can shut off, even if he wanted to. BR: I think he will think about chess his whole life. Chess puzzles. It is one of those games where you could spend a whole life on it and never 'solve' it. BR: It's truly the insoluble game. When you play a video game the game is over, you won. That's impossible with chess. You can never totally master the game. It's impossible. No one can. There's always something you can learn and you can only get closer and closer to mastering the game more perfectly.

How does Magnus feel about being called the 'Mozart of chess'?

BR: He was asked that by Bob Simon [in a 60 Minutes interview]. He responded, "Mozart didn't know why he became so good." Magnus looks at it as a mystery himself. He can't really explain why he became the best against all odds. It's a good way of explaining how good he is to people who don't know chess. They know who Mozart is. He's obviously fiercely determined. Is he self-aware or not self-aware? BR: Not self-aware. That's a good thing when you're making a documentary. Other people who are very self-aware try to play themselves. There is that theme of loneliness in the film. By virtue of his gifts he's kind of an isolated person. BR: Magnus feels lonely, like all people do, but I think that he feels especially lonely because playing chess, it's all up to you. It's not about luck. It all depends on your skills and it's on such a high level that you can't share your thoughts with anyone else because your ideas are kind of out of this world. He sees things [that are] so complex and then others won't understand so that's why he doesn't share kind of his inner demons with anyone. That's easier for him because why do you need to share an idea that another person won't understand, who won't relate to it?

It's a really suspenseful film, building toward Magnus' first attempt to win the World Chess Championship against a very difficult opponent, Viswanathan Anand.

BR: That's what we aimed for. It was so difficult to make the story look easy. I think it's much harder to tell a story in a kind of linear way than jumping back and forth or having many main characters for you to go to. Almost all the scenes are with Magnus. The only time we show a different perspective is with Anand. Anand is the antagonist in the story. He represents the opposite approach from Magnus -- winning by extraordinary preparation on the computer. BR: Magnus has lost many games against Anand where Anand has won purely by preparation. His computer programs can find all the games that Magnus has played in history and then they find his weak spot. Anand knows what Magnus' pattern is and he just plays the first 25 moves without thinking. You can imagine what that does with a sport like chess. It's not fun anymore. It's almost like playing a computer then. And that's one of the points I tried to get through in the film. So the championship is really about Magnus trying to get Anand out of his computer preparation because then it's man against man, mind against mind.

BR: I think we use way too much computers in our daily life, with the mobil phones, sitting at the computer. Everything is through computers. We forget the human element. And what's beautiful about being a human is our intuition, our creativity. We do mistakes, but that's a part of being human. We use too much computers today and we forget to play. These are kind of the main motives in all my films. That's what really motivates me to tell stories. We're getting more and more away from what's the natural thing for us as humans. All mammals in the animal kingdom, all children in the animal kingdom, they play. They play to learn and then we forget it, and especially today. We give children iPads so they get over-stimulated. They forget to be creative, they forget the playfulness that is only to have fun, without kind of the rules... It's so important that we just play for the fun of it.

For a thousand years chess has kind of been the touchstone of intellect.

BR: Magnus for me he is a modern icon for creative thinking. For continuing to be playful. And I really hope that this message can get through through the film, that even though he didn't learn chess in a structured, disciplined or computerized way he became the best at the sport. For a thousand years chess has kind of been the touchstone of intellect. That a little boy from Norway becomes the best, the highest rated in history at that sport -- against all odds -- I think that's a story worth telling.

Has the film played in Norway? What was the response? Sigurd Mikal Karoliussen: Great response. And now we have released the film on iTunes and VOD. Now with the chess championship almost a million Norwegian people are sitting up until 3 o'clock in the night to watch the game... It seems like everybody's watching. What has been the key to working successfully together as producer and director? SMK: That we want to do the same movie. That's the most important part. Because if I want to use his way into the project to make another kind of movie than he wants... And it's very often that you find that out very late in the process -- because you think you want to do the same, but you have a different purpose in making the film. We wanted to make the same film.

Interestingly, you also used a screenwriter on the project, Linn Jeanette Kyed.

SMK: In Scandinavia it's very important to see if a screenwriter can help you and in this project our screenwriter just looked through all the material and then she came back and said, "This is the story I see in the material,' which was the story we wanted to tell, so that made it a real good collaboration. And she stayed with the project all the way through the editing. [At one point] the editor took a completely other approach to the project and we all thought, "Oh, this is so bad. What to do?" And then the screenwriter came back and said, "This is not what we talked about." So she helped the project get back on track. So this has been a really interesting and very creative and good project. We're at an interesting moment in popular culture where Scandinavian storytelling really seems to be resonating with audiences in the U.S. and Britain. Why do you think that is? BR: We have a great funding system in Norway that helps us be able to use a lot of time to get the story right. Magnus wouldn't have been made into a feature length documentary without the Norwegian funding system. And we could use a year in the editing room. And if you had seen the film in the early editing process it was an awful film. Didn't work at all. So I think that we're really fortunate. We had to work so much in the editing room to make the audience feel what Magnus felt. It was really hard. Just imagine looking through 50 hours of only chess playing in the World Chess Championships, looking for reactions, small emotions, just looking over and over again, editing it down so we can feel the tension. It takes a lot of time. SMK: We have the best system in the world. We complain a lot too, of course, but compared to everybody else it's a really great system.

Magnus has done so much to get more people interested in chess.

BR: Magnus has revolutionized chess. He brings the human element back to the chess game. And for chess players it's much more fun to watch it when it's a battle of the minds, not when it's who is using the computer best. And Magnus really brings his creativity and that was kind of a new hope for the game... If you go 20 or 30 years into the future he will prove to be one of the icons, because of what he represents.

|

AuthorMatthew Carey is a documentary filmmaker and journalist. His work has appeared on Deadline.com, CNN, CNN.com, TheWrap.com, NBCNews.com and in Documentary magazine. |

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

Proudly powered by Weebly

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

RSS Feed

RSS Feed