|

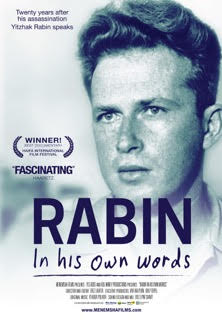

Director Erez Laufer on his Rabin doc, Netanyahu, and Hillary vs. Trump: 'I don't know much about Trump's foreign policy'

Some political assassinations are more impactful than others.

Not to be flippant, but President William McKinley's -- not so much. Abraham Lincoln's -- that's another story. So it is with Yitzhak Rabin, who was assassinated in 1995 by a right wing Israeli enraged by the Prime Minster's attempts to forge peace with Palestinians. You can kill the person but you cannot kill his ideas and his words.

That the Middle East peace process has utterly stagnated in recent years is due in no small part to the removal of Rabin from the scene. He had both the stature and the will to bring Israel closer to a durable peace than any other political figure of his time.

From the point of view of Rabin's political opponents, "That was the most successful political assassination -- one of the most successful political assassinations in history," notes Erez Laufer, director of the new documentary Rabin In His Own Words.

Rabin In His Own Words opens today in Los Angeles [Laemmle Royal Theatre], New York [Lincoln Plaza Cinemas] and South Florida. As the title suggests, the film is composed almost entirely of interviews, audio recordings, off-the-record conversations and personal correspondence of Rabin.

Nonfictionfilm.com spoke with Laufer after he made his way to New York from the Hotdocs Film Festival in Toronto, where Rabin In His Own Words screened. Nonfictionfilm.com: How did the Hotdocs screening go? Erez Laufer: It was the first time that I was present in a screening out of Israel so for me it was very moving to see that the audience got very moved by the film and the questions were good. So I was happy. Because I was afraid of that, actually. NFF: You thought you might not get that type of reaction? EL: I had a confidence already that the film can play here and not just in Israel. But it's different when you are present in the hall and you see it and you experience it.

NFF: What has the reaction to the film been like in Israel?

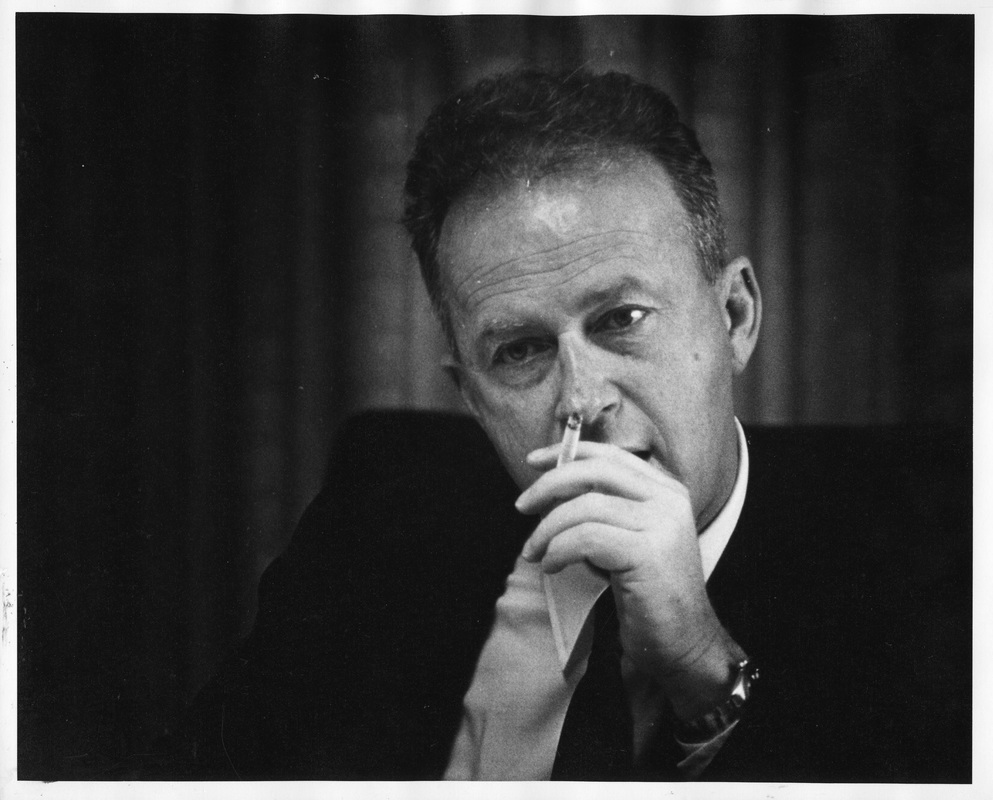

EL: It was controversial when they published in the mainstream news the Rabin quotes from the off-the-record tapes that we found for the film... And I'm talking about three things in particular: one is the declaration that he was ready to give up the [Occupied] territory already in '73, that he always saw the Territories as a means to get peace and not to [create] settlements. And the other one is that he already in '76 said the if we're not going to get solutions Israel will be an Apartheid state. It took years [more] until people used that term and it always had controversy when you say it. And the third thing that he said is that the settlers are like cancer in the tissues of the Israeli society. And so of course that made the news, even though in the memoirs he said it already. It was not the first time that the public knew that he called them a cancer in the 70s, but it was the first time that it was in his own voice. And in a way it shows also that the friction between him and the right wing, it didn't start after he signed the Oslo Agreements in '92. It's back then in the 70s when he tried the peace with Egypt and he signed the interim agreement with them. NFF: Tell me about your decision to construct the film -- as the title says -- "in his own words." EL: You can kill the person but you cannot kill his ideas and his words. So I think there is something almost chilling of getting someone that died 20 years ago to tell his story and almost bring [him] back to life in a big screen -- bringing his ideas and words. And for me something interesting of choosing this method is almost the influence of the "direct cinema" of [D.A.] Pennebaker. Of course this is not a direct cinema but it takes the same rules of not using experts for explanation and interviews. You understand what I'm saying? It's the same aesthetic. You let the story unfold in front of the viewers' eyes.

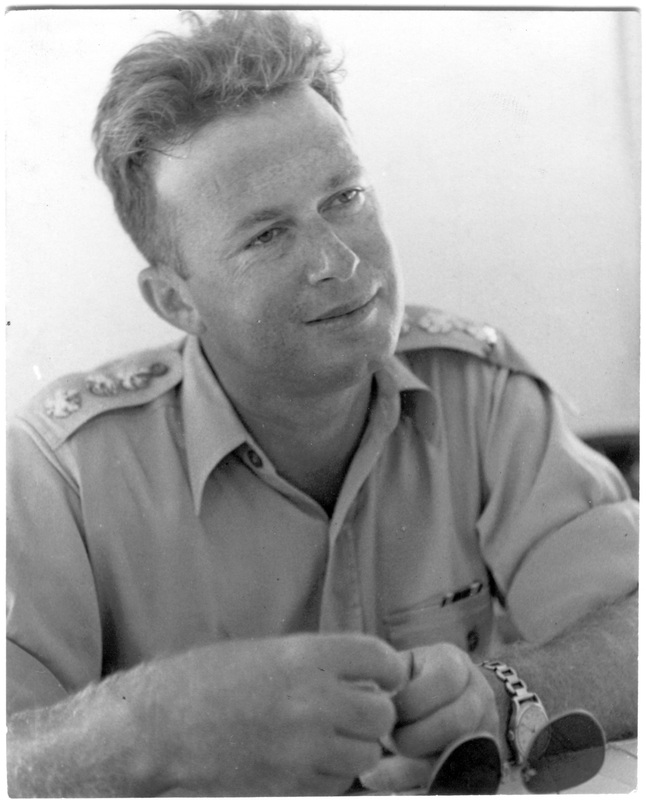

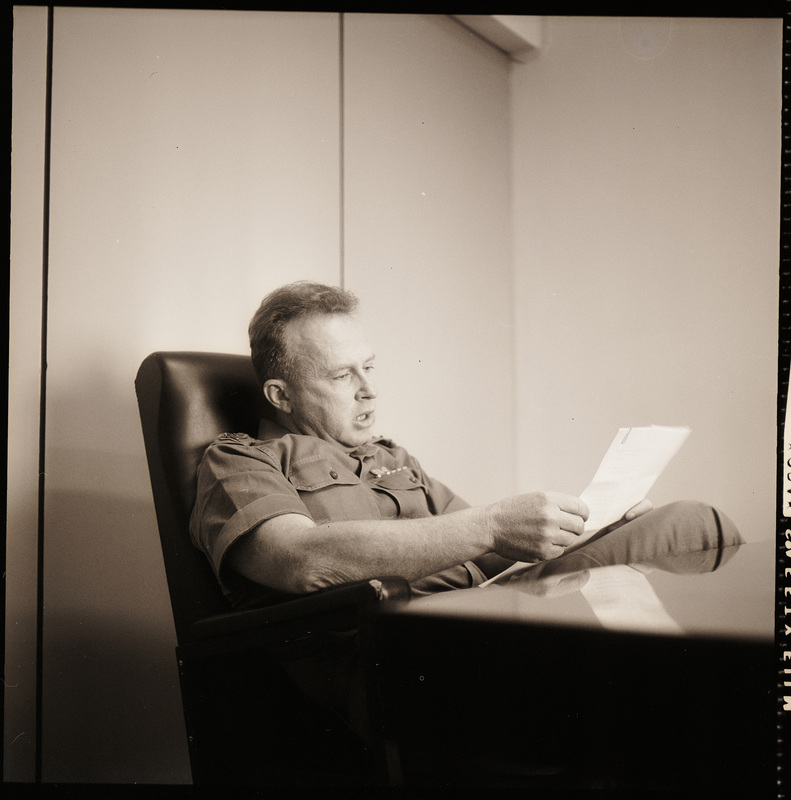

NFF: In the film Rabin says he did not intend to become a military man and so he was sort of an unlikely soldier. And he seemed like an unlikely politician, just temperamentally. He didn't seem born to it.

EF: You can see from his childhood he was a smart kid. He was good in math. He was supposed to go to study water engineering in Berkeley... he got a scholarship for that. When you see that he is the Chief of Staff [of the Israel Defense Forces], a military man, you don't see him as a politician, but he always saw himself as a statesman and there is a difference. In the military when he took over, he won the '67 war, he didn't think about those lands [seized] as a means for expanding the country. He thought he was avoiding the threat that was on Israel's security and he thought that he had the means to solve the dispute between the Arab and the Israeli, not [to expand] the border as an aim for itself. So I think he didn't see himself as a politician but he did see himself as a statesman also when he was in the military. For some reason I refuse to treat Rabin as a controversial figure. I think now when you present an idea that you have to make peace, to give up territory, then people categorize you as a leftist, yeah, but we have to remember Rabin was not a leftist. Rabin was the chief of staff [of the IDF] and the Prime Minister of Israel. So, think, it was the official policy of the government of Israel [to negotiate land for peace].

NFF: It's extraordinary to think how much things have changed in terms of perceptions of a peace process over the 20 years since Rabin's assassination.

EF: When I grew up, in high school, that was the legit argument -- 'shall we call the territory a liberated territory, occupied territory or kept territory?' It was a legitimate [argument] and now it seems to be different. NFF: There doesn't really seem to be a peace process anymore. Is that an accurate statement? EF: I think that's a very accurate statement. Listen, I'm not a politician but I think there isn't one now. But I think the same dispute there was 20 years ago is still in place -- [only] the situation got worse. NFF: It was fascinating to hear Rabin condemn the expansion of settlements in the Occupied Territories. There doesn't seem to be any kind of serious opposition to that one hears about in Israel. And increasingly in the U.S. it's become a politicized thing, that you can't even criticize settlements from an American viewpoint EF: I think there are different kinds of hardliners. There's the hardliner who will be tough for a security reason, and with them you can talk. But then there's the hardliner that [backs settlements] because of mythical, Biblical reasons, because "the lands belong to us from 2,000 years ago and doesn't matter who lives there," etc., etc. And I think most of the population of Israel I don't think they care so much about the settlements, but they care about the security. So the leaders like to blur those lines. You understand the distinction? Because you can be a very military man and you think, oh, we cannot afford the missiles being in the West Bank, etc., etc., etc.

NFF: I don't mean this question as provocative, but late in the film we see Benjamin Netanyahu, then in the opposition, thundering against Rabin's peace initiatives. In a speech he urges his supporters to vigorously oppose the peace plan by "legitimate" means. But we see the passions that were unleashed -- not just by Netanyahu alone. My question is to what degree do you feel he bears any responsibility for what happened to Rabin?

EF: I don't know if it's a provocative question because in Israel people out loud accuse all the leaders of the right wing -- after [the assassination] happened -- of not taking some responsibility. Because no one thinks that Netanyahu wanted someone to kill Rabin and he did use [the term] "legitimate" opposition... I think the anger toward them was more that they didn't want to acknowledge anything after it happened, to take some responsibility for the manners of the discussion. They could have said, "Okay, we didn't know it will go that far. We could have [tried] to restrain our followers," or something like that... And of course for Bibi Netanyahu it was a very delicate question because actually the fact that they assassinated Rabin made it possible for him to get elected [Prime Minister].

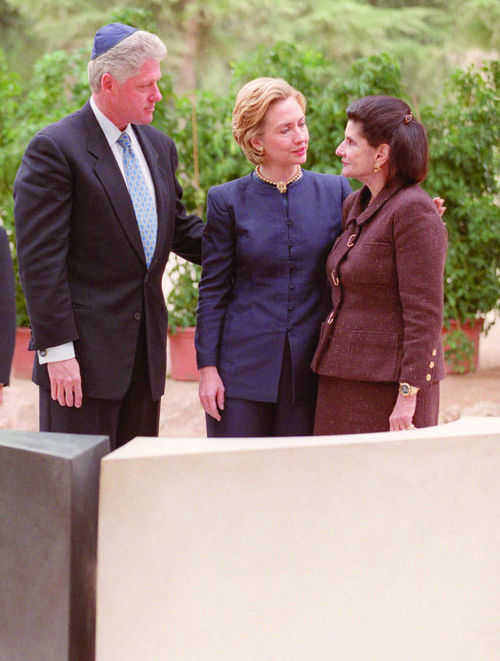

NFF: In the film we see images of President Clinton with Rabin, and photos of then First Lady Hillary Clinton with Rabin and Leah Rabin. We have the likelihood of either Hillary Clinton or Donald Trump becoming the next President. Do you have any thoughts on how either of them might impact the peace process in the Middle East?

EF: I must admit that I don't know much about Trump's foreign policy. NFF: No one does. EF: As a private person, as a filmmaker, I can express my feelings that of course I would like Hillary to be the President of the United States. But you know it's not for me [to decide] but if my Prime Minister, Bibi Netanyahu, is interfering in American politics, going against your President [Barack Obama], I can express myself as much as I want... I think it's more important to ask my Prime Minister why he's trying to interfere in American politics.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu addresses a joint meeting of Congress in March 2015, at the invitation of then House Speaker John Boehner [upper left]. Next to Boehner is Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah). Netanyahu used the speech to attack President Obama's negotiations with Iran over its nuclear program. AP Photo/Susan Walsh

NFF: Netanyahu is exploiting the growing politicization of US-Israeli relations. Evangelicals and many conservatives here are increasingly resistant to any criticism of Israeli policy vis à vis the Palestinians or Arab states.

EF: I hope this film can show that you can be an Israeli patriot and still fight for the peace. I hope this film can show it. First of all, it's a portrait of a person, of Rabin, but politically I'm sure that this is a strong message. |

AuthorMatthew Carey is a documentary filmmaker and journalist. His work has appeared on Deadline.com, CNN, CNN.com, TheWrap.com, NBCNews.com and in Documentary magazine. |

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

Proudly powered by Weebly

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

RSS Feed

RSS Feed