|

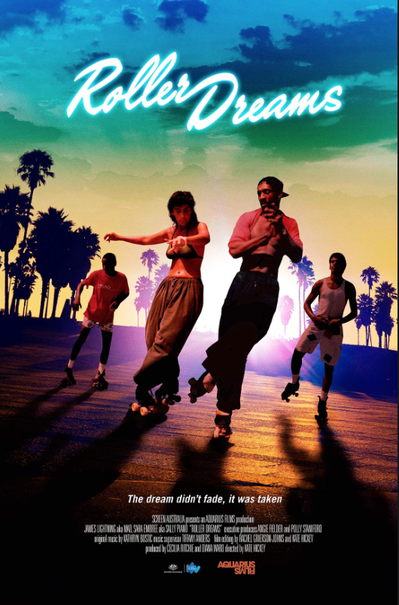

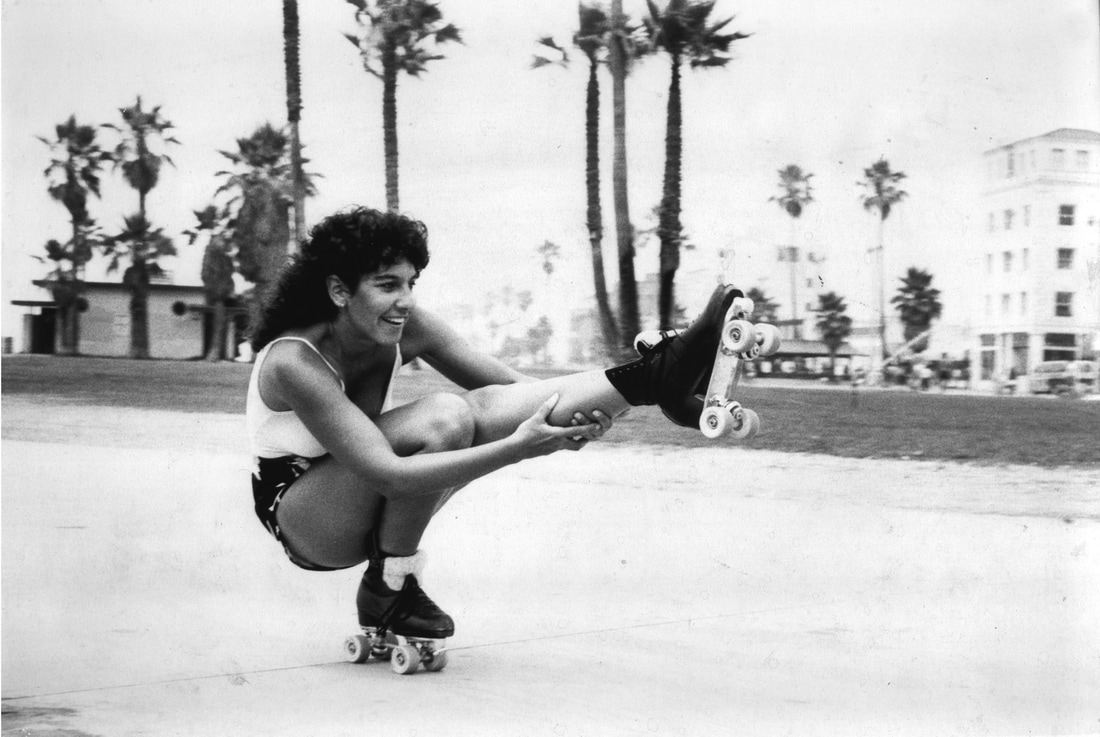

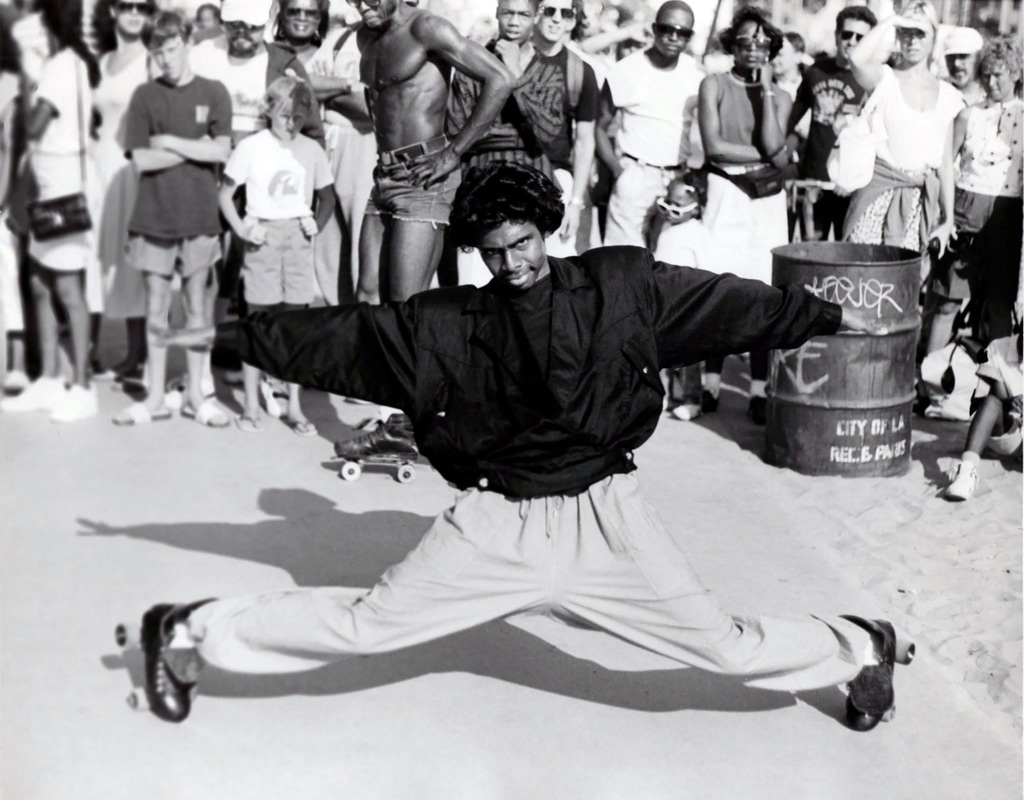

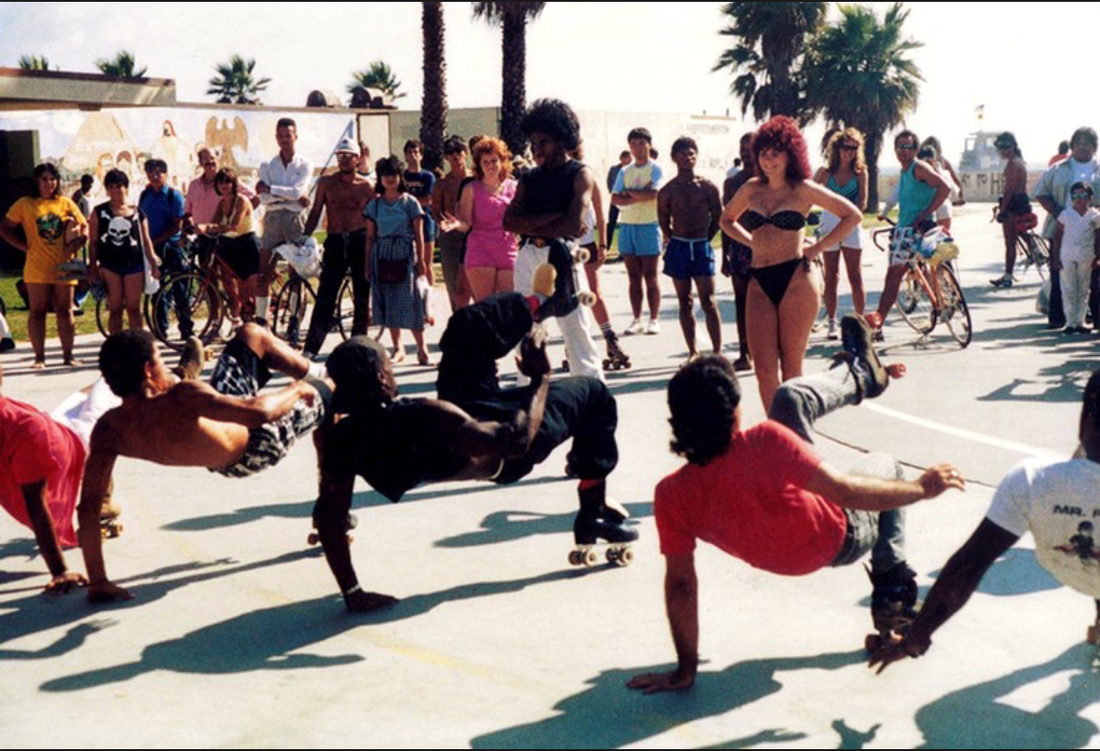

Kate Hickey's film stars roller dancing's hottest talents, who put L.A.'s 'black beach' on the map The top attraction at Venice Beach these days is probably the skate park where kids on boards do their tricks in front of an admiring public. But decades ago it was another activity on wheels that captivated crowds -- roller dancing performed for hours on end by an exuberant, multi-ethnic cast of characters who turned skating into an art. Their story is told in the documentary Roller Dreams, which played last week at the LA Film Festival's venue in Santa Monica, just up the coast from Venice Beach. Xanadu: An idealized place of great or idyllic magnificence and beauty. The film marks the directorial debut of Australian native Kate Hickey, who uncovered countless hours of archival video of roller dancers joyously doing their thing in the 1980s and 90s. "You get a sense of freedom, definitely, from what they do," Hickey told Nonfictionfilm.com. "They're letting their light shine out through their moves." Those moves included tightly choreographed line dances and individual displays of dancing prowess, all of it under the stern eye of James "Mad" Lightning, the acknowledged leader of the disparate crew of roller dancers. Mad -- the central character in Roller Dreams -- was not only a virtuosic skater himself, but he engineered the mega-boom box that made roller dancing to music in that public setting a possibility. Most of the skaters showcased in the film came from rough sections of L.A., with limited economic and creative opportunities. Venice Beach became a haven for Mad, Duval Stowers, Larry Pitts, James "Jimmy" Rich, young Terrell Ferguson, Sara Messenger (aka Sally Piano) and others. "It was a place they could come and be free and also get their 'fix' for the week," Hickey observed. "They would be sweltering away in South Central all week long and doing their own things -- preparing for the weekend when they'd come and really let their freak flag fly and get the applause that they deserved." As Mad puts it in the film, "Not having a childhood, this was my childhood." Hollywood pumped out a series of roller-themed films 1979 and 1980 (Roller Boogie, Skatetown, U.S.A., and Xanadu), but none of those stories bore any resemblance to the lives of the real dancers. Moviemakers co-opted some of their dance moves, but built the films around white characters. "None of their passion and the life force of it came across in these movies. It was just like a quick trend really and treated like that," Hickey stated. "And they'e hokey, the movies. Xanadu got a Razzie [nomination] for worst film of the year." The term Xanadu, which comes from the Samuel Taylor Coleridge poem "Kubla Khan" of 1798, refers -- according to one definition -- to an "idealized place of great or idyllic magnificence and beauty." Alas, for Mad and his cohorts, the Venice Beach of their dreams was to prove as ephemeral as the Xanadu of Coleridge. The film suggests monied interests, with the assistance of the police, shut down the dancers because they feared the 'urban' crowds drawn to witness the free shows. "They wanted Venice to become something else -- 'they' being, you know, the money, the real estate guys in the area. And then the cops were also a part of that, being given the brief, 'Go and shut them down. These crowds are dangerous. Anything could jump off at any moment. Let's take out the music,'" Hickey said. The film contains archival video of heavy machinery ripping up the smooth, level pavement where the roller dancers performed. "That's [the work of] the Venice Beach Parks and Recreation Authority," Hickey maintained. "Ultimately they said, 'We'll give you this area' and a lot of them [roller dancers] went through the legal procedures to try and get the area they wanted but it just didn't turn out like they were told." The Venice Beach of today has been transformed from a gritty place to a gentrified one, with homes easily fetching $1 million or more. It's no longer the 'black beach' of decades past. Roller dancers, who helped give the beach its identity and made it world famous, now are relegated to an out-of-the-way spot. "Basically they're behind the skateboarders who got prime real estate," Hickey said. "Our guys are effectively in a hole --the area is raised around them, so they're very hard to see. They don't get as much foot traffic there anymore, so it's important for a film like this to really make them cool again and be like, 'Wow, they made an impact on the area and brought the crowds in to begin with so they shouldn't be forgotten.'" Roller Dreams won the audience award at the Sydney Film Festival shortly before it screened at the LA Film Festival. Distribution plans are in the works, Hickey told Nonfictionfilm.com.

"We're talking to three interested sales agents. We really think Netflix would be a perfect place for it to just spread worldwide," Hickey said. "We're really hoping to go to Europe where skating is huge. Already after these two festivals we've had a lot of online, Facebook people, [building] excitement around it. Hopefully it continues to be an audience-pleasing film, like a film for the people." The primary dancers featured in the film -- with the exception of the late Duval Stowers -- reunited for an emotional conversation after the screening in L.A. Some of them still perform at Venice Beach, a place where they spent some of the best moments of their youth. "They're definitely like kids at heart and that's what I loved," Hickey said. "I loved that idea of the Peter Pan syndrome -- that they never grow up and Venice is their Never Never land." |

AuthorMatthew Carey is a documentary filmmaker and journalist. His work has appeared on Deadline.com, CNN, CNN.com, TheWrap.com, NBCNews.com and in Documentary magazine. |

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

Proudly powered by Weebly

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

RSS Feed

RSS Feed