|

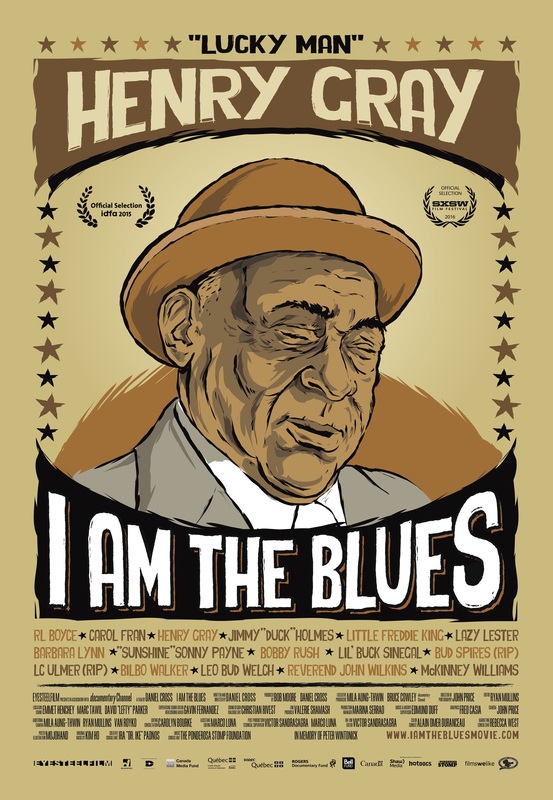

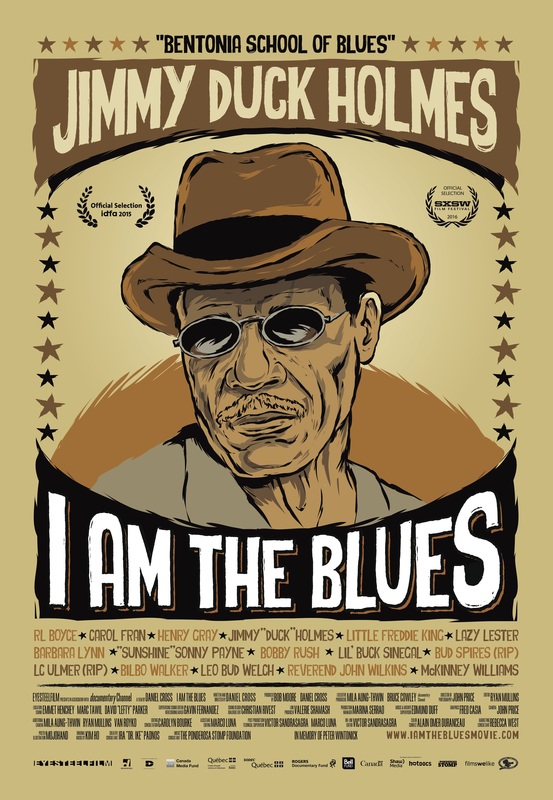

Daniel Cross film returns to the music's roots, rediscovers blues greats

Filmmaker Daniel Cross may be Canadian, but he's immersed himself in a distinctly American art form -- blues music, which sprang from the Deep South more than a century ago.

For his new documentary I Am the Blues, Cross went down to the Crossroads as it were -- to the Mississippi Delta, the Mississippi Hill Country and parts of Louisiana to reconnect with the origins of the music and to hear from some of its finest remaining practitioners. I didn’t want to go to Chicago and New York and hunt down celebrities. I wanted to go back into the South, [find] who was living there and still playing the blues and had pedigree.

The film just held its North American premiere at the SXSW festival in Austin, Texas, following the world premiere last November at the International Documentary Film Festival in Amsterdam. It will play at Hot Docs in Toronto, with screenings scheduled for May, 2, 4 and 7.

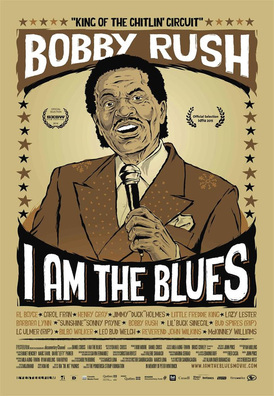

Cross' guide through much of the film is veteran blues man Bobby Rush, the "King of the Chitlin Circuit," who at age 82 is still playing music and entertaining across the country.

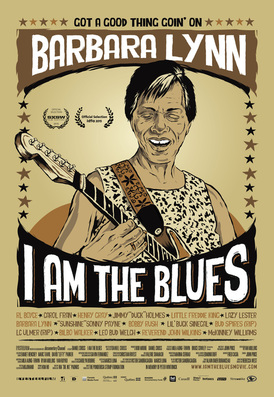

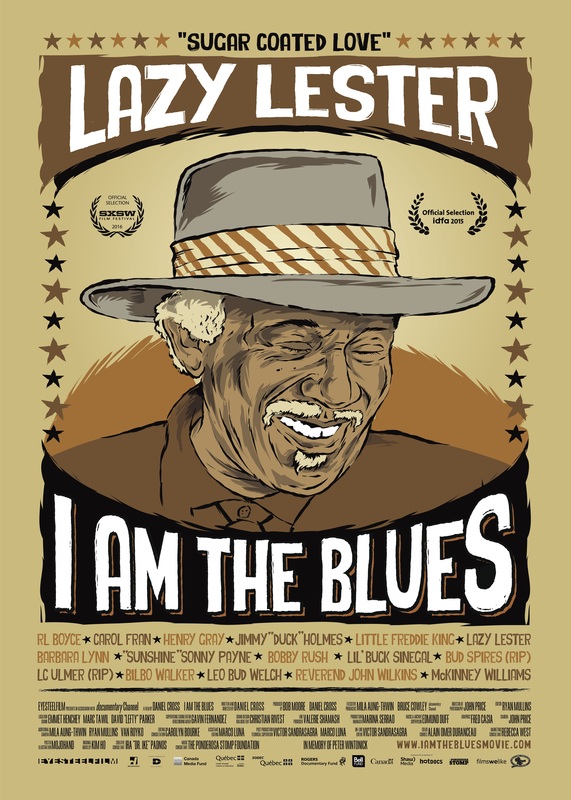

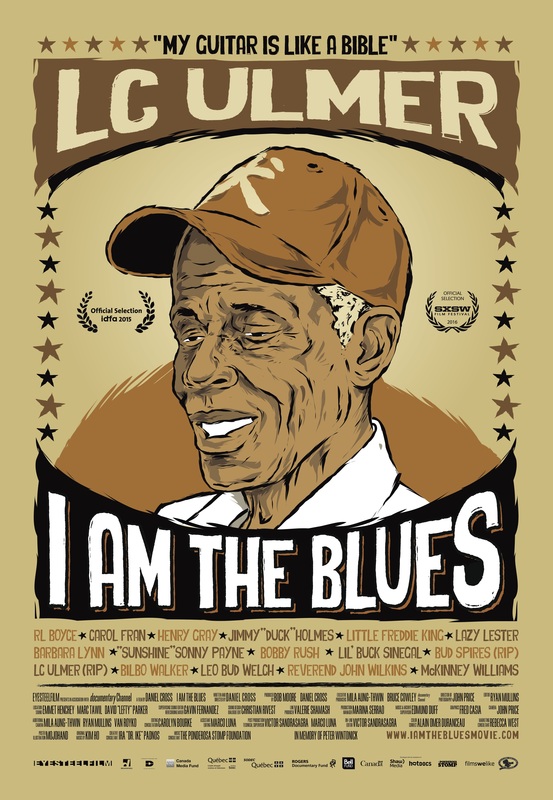

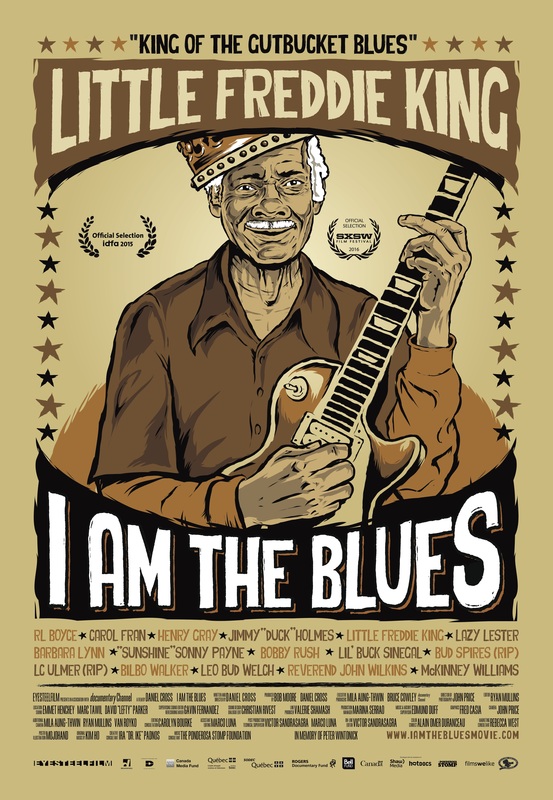

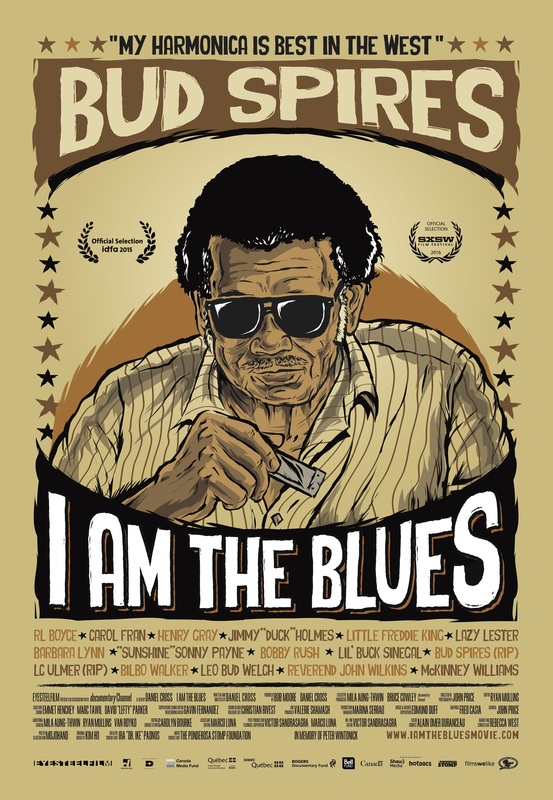

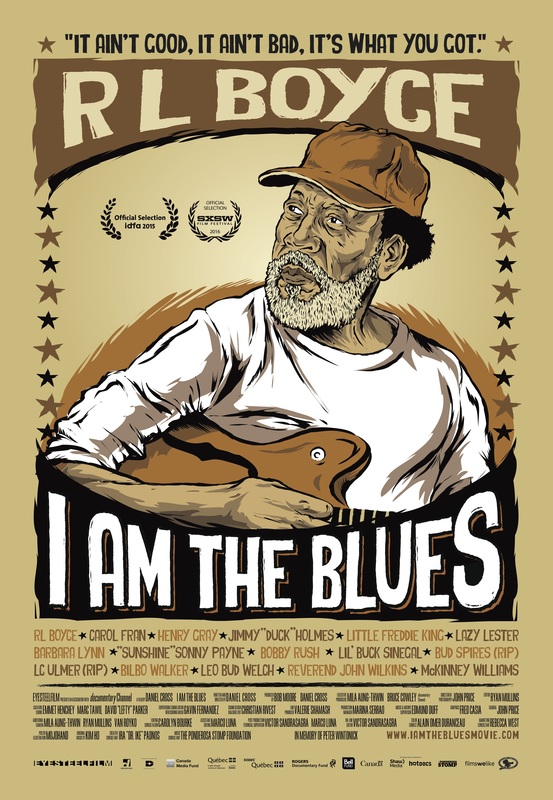

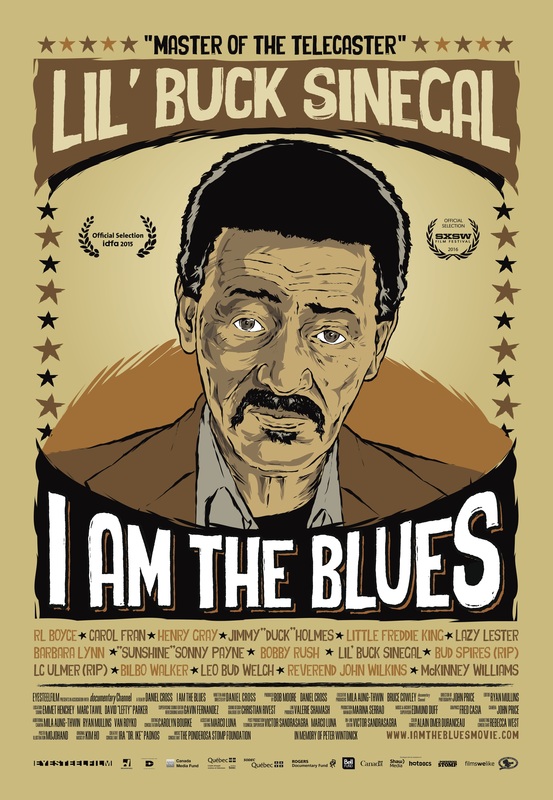

Nonfictionfilm.com spoke with Cross and Bobby Rush at SXSW. The director credited Ira "Dr. Ike" Padnos, founder of the Ponderosa Stomp Foundation in New Orleans, with pivotal support in realizing the documentary project. Daniel Cross: It's Dr. Ike that took me on the road and introduced me to everybody. We went to Bobby’s [Rush's] home and we went and met Barbara Lynn, Jimmy "Duck" Holmes at the Blue Front Cafe [in Bentonia, Miss.], and Carol Fran and Little Buck Sinegal and Lazy Lester. He just took me on a drive through Mississippi, up to Memphis and back back down through Lafayette [Louisiana], back to New Orleans where Little Freddie King was. And we just literally stopped at everybody’s house. He knew ‘em all because he had employed them all because the Stomp kind of re-discovered many of these blues musicians… [For my film] I looked for musicians who didn’t have management. I didn’t want to deal with a bunch of lawyers and managers. And I didn’t want to go to Chicago and New York and hunt down celebrities. I wanted to go back into the South, [find] who was living there and still playing the blues and had pedigree. Bobby Rush: I think this was the best thing he could ever do because going back to the South and getting guys who didn’t have the big popular name like the Muddy Waters and Howlin' Wolf -- you got to understand, this is where it all started from, even the guys who you knew in Chicago and New York, they came from this area, like Mississippi and the Bottom, Louisiana and Arkansas and migrated to Chicago. He [Cross] looked over that and come back to where it started from in the beginning. This is the root of it.

DC: There’s like 11 musicians in the film and how it was able to be held together was Bobby kept coming to the different places [with me]. So Bobby was the glue that could help hold the whole story together, like the central focus. So as a result we would go on these road journeys with Bobby — we’d be in Jackson [Miss.], and we’d be driving to Lafayette. Or we’d be driving out to Po’ Monkey's in Merigold [Miss.] or up to the Blue Front in Bentonia. These journeys became where Bobby opened up the most because as he says he does all his writing and thinking on the road. He loves the road. It’s the best thing that ever happened to him. And we’re driving past America, stopping in Tutwiler [Miss.], stopping in Dockery Farms, the Dockery Plantation [in Miss.] and out in Lafayette.

If you go through the Delta it’s been pillaged. The people needed to leave because of the living standards. [The conditions] were like slavery, basically. And so they all went to Chicago. And you go back now and there’s not a community of blues people except for in Clarksdale [Miss.]. So we’d find "Bilbo" Walker in Alligator [Miss.], we’d find Jimmy "Duck" [Holmes] trying to do everything he is in the Blue Front Cafe… You find just a random blues man living out in his farmhouse kind of but not this community [that existed before].

NFF: Bobby Rush, you're one of the last of the old-time blues greats. How does that feel?

Bobby Rush: I not only feel good about it, I’m blessed to be here doing what I’m doing. I believe now if I’m not the oldest one I’m at least the ugliest one left doing what I’m doing. I believe myself, Buddy Guy [age 79] would come next. We have two guys in the business — we’re talking about black entertainers now — that’s older than me: that would be Chuck Berry [89], Fats Domino [88], but they don’t consider themselves as blues guys. So when you come to blues guys I’m probably the oldest blues guy around in entertainment. Now we have some musicians that’s older. We talk about Henry Gray [91] in Baton Rouge now... he’s older than all of us. In fact, he’s older than dirt. [laughs] NFF: In the film you explain what it was like playing the Chitlin Circuit back in the day. BR: The Chitlin Circuit originated from really serving chitlins — the hog guts — that’s what they fed us for playing. We played for food every night. I remember I have two plates of chitlins. I sell one and eat one. And five hamburgers — I eat one and sell four, for 25 cent apiece. My first gig the guy was paying me 12 dollars a month. Twelve dollars a month in 1951. Twelve dollars a month. Then I went to Chicago where I played for seven dollars and 50 cent a night behind a curtain where they wanted to hear my music but they didn’t want to see my face. So we come from a long ways. Cross to Bobby Rush: You’re one of the originals that went into Chicago, became a frontman and made it back out. A lot of those guys died young; they weren’t with their families. BR: Lived fast and died young. Lived too fast. Story on me. I left Louisiana in 1947, went to Pinebrook, Arkansas and stayed with my father who was a minister and pastor of a church. [In] 1951 I moved to Chicago and I lived there for 48 years. And now I live in Jackson, Mississippi. So I’ve been all around across the country and back and forward through this world. And I saw a lot of things. But I’m one of the few blessed people to make this whole turn and still survive the rat race and now my audience probably 50-50 white and black audience. That’s not true of most guys in my industry. I don’t get into name calling but most of the guys who have the crossover have a 99-percent white audience, very little black audience. But I’m about 50-50.

NFF: What makes a great blues song?

BR: I think what makes a great blues song is what you talk about in the sense [of how] you approach it. But I’m one of the few guys who can approach it in a way where I can get away with it because I talk about the truth. The truth, a lot of times in blues singing, doesn’t sit well. It’s kind of hard to look at a man and say, “Hey, you got the ugliest baby.” But that’s a blues song. [laughs] That’s a blues song... I talk about fat ladies because they got to have some lovin’ too. Then I also talk about skinny ladies. Some of ‘em so skinny you turn sideways you think they’re gone. That’s pretty skinny. DC: By and large he talks a lot about ladies. BR: I can get away with that. And I talk about it and laugh about it. I talk about the garbage man who stole my woman. Of all men she had to go with the garbage man. What a way to go. DC: They’re singing the blues but they’re working their way with their music out of the blues. BR: Exactly. DC: Their optimism — for what they’ve lived through, being raised in such poverty and in such racial discrimination and stuff and their attitudes today and their positive approach — it’s really inspiring. To meet them is a real honor, to see these people. Because you’re right, they’re poets. They’re smart and insightful people with huge hearts and a lot of passion and care and love and they manage to keep that while living through years of pure hatred towards them.

NFF: There is a question implicit in this film. Will the blues survive?

BR: From my standpoint I think the future of the blues is good now. But you got to get young guys who fall in love with the blues... It’s a hurting thing to me to see that we don’t have any young guys, black guys, who want to be involved with something like this, with playing the blues... the writers don’t want to write about these things. DC: There’s definitely serious issues if we think of America... definitely serious issues. And if we think of the blues traditionally coming from black musicians and you think of what young black people are living through today in America with police violence and this whole issue. That will generate the blues. Technology’s changed. Their musicology has changed. They won’t do it in the same way that, you know, Charley Patton and Robert Johnson did it. But their lyrics in rap and hiphop is more from the blues than from any — they’ve been empowered more by the blues than anything else, whether they know it or not. BR: Some of the guys singing the blues or rapping don’t know they’re singing the blues. They don’t really know. They talking about their trouble, talking about what they in, the situation. If that ain’t the blues, what is the blues? |

AuthorMatthew Carey is a documentary filmmaker and journalist. His work has appeared on Deadline.com, CNN, CNN.com, TheWrap.com, NBCNews.com and in Documentary magazine. |

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

Proudly powered by Weebly

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

RSS Feed

RSS Feed