'The Witness': new doc on Kitty Genovese murder case--the crime story everyone thought they knew6/15/2016

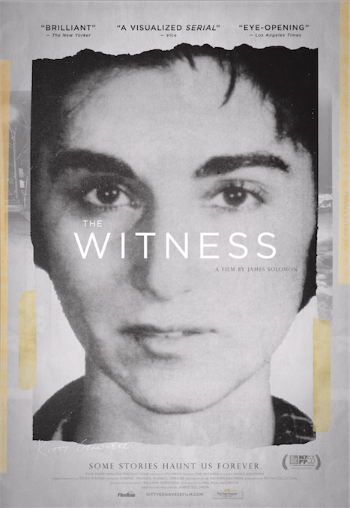

Genovese's brother, with help from director James Solomon, uncovers what really happened the night of Genovese's death

For more than 50 years the name Kitty Genovese has remained imbedded in the nation's collective memory -- the young woman's murder in New York a confirmation of our worst fears about the indifference of our neighbors in urban America.

Her story became a "morality play," as director James Solomon puts it, a narrative that spoke to an inchoate need among Americans to make sense of their changing country, even if the story as reported was inaccurate. In November of 1963 John Kennedy had been assassinated. Kitty Genovese was murdered just four and a half months after Kennedy's assassination. The stories that were running in the [New York] Times at that time -- and in other papers -- was who are we [as a people]? Who are we?

No one was more deeply affected by Kitty Genovese's killing than her younger brother, Bill. In Solomon's fascinating documentary, The Witness, Bill Genovese sets out relentlessly to discover what truly happened the night of her death and how reporters at the time got the story wrong.

The film plays out like a true crime story comparable in a sense to The Jinx, but it's also a sibling love story, a deeply absorbing piece of social history, a critique of journalism, a complex account that touches on race, and much more.

The Witnessopens Friday in the Los Angeles area [Santa Monica, Irvine and Pasadena], as well as Houston, Toronto, Columbus, Ohio, Santa Fe, New Mexico and Winston-Salem, North Carolina [and it plays at the Laemmle Claremont 5 in Los Angeles Saturday and Sunday]. The film opened in New York on June 3rd.

Nonfictionfilm.com spoke with Solomon in Los Angeles, shortly before the film's theatrical release.

Nonfictionfilm.com: What do most Americans know of the Kitty Genovese story? James Solomon: The iconic story was on March 13, 1964 in New York City a young woman, 28 years old, was brutally attacked in front of 38 eyewitnesses over the course of a half hour and not one called the police. That story then helped lead to the establishing of the emergency 911 system, Neighborhood Watch groups, Good Samaritan laws. So she became this kind of iconic victim and an emblem of urban decay. She's really this symbol of urban apathy -- that if something were to happen to you no one would come to your aid, that you're essentially alone. That's what she has come to symbolize for many over many, many decades.

The New York Times -- on the 40th anniversary of Kitty's murder -- revisited its own story and questioned whether they had been accurate in their reporting. And Bill was then propelled to find out for himself the story that had literally and figuratively shaped his life -- what actually happened. And he allowed me to tag along. And the result is The Witness.

[Note: Genovese tracked down people who had heard Kitty's cries the night she was killed. They exploded the myth created in the Times' original reporting that dozens witnessed the attack and did nothing. Two did call the police; one woman cradled the mortally wounded young woman].

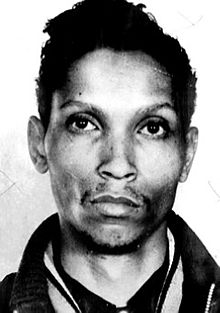

JS: Every day spent with Bill and who he was speaking to, who he was finding, what he was uncovering, it was always worthwhile. It was unclear as to where we were headed [with the film], for sure... You're sort of unraveling an iconic story that we've all come to know and it was leading us in directions that were continuously fascinating and surprising... It is sometimes daunting because you don't know when you're over [with the investigation] and as Bill says in the film, "I'll know when it's over." It's like, "Clue me in, because I'd like to know too." The film is fundamentally an incredible investigative mystery -- multiple mysteries: what happened that night? Who was Kitty Genovese? How did that story come to be? What was this person, Winston Moseley, why did he kill Kitty Genovese? What motivated him? ...What Bill does in the course of an 11 year investigation is nothing short of astounding.

JS: The Witness in many respects is about loss. It's about false narratives, it's about the power of holding on to false narratives because you need to cling to them in the middle of the night to get through a night if you hear screams outside your house, or a false narrative you might cling to over the course of 50 years. It's about forgiveness.

NFF: Certainly the film has a lot to tell us about how journalism is deeply rooted in narrative. Some people would like to think reporting is the mere relaying of facts. However, it's imbedded culturally, in what we think of as a story. Why do you think we needed the story of Kitty Genovese at that time, 1964? JS: You have to keep in mind that in November of 1963 John Kennedy had been assassinated. Kitty Genovese was murdered just four and a half months after Kennedy's assassination. The stories that were running in the Times at that time -- and in other papers -- was who are we? Who are we? And part of that was fueled by a kind of heightened crime rate... a lot of urban flight, a lot of people leaving [the city]. A sense of the country and the cities in particular going to hell in a hand basket. And along came this wonderful morality play that sort of reinforced this narrative.

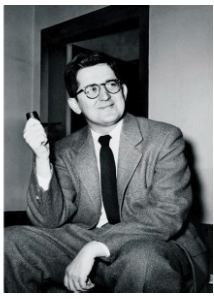

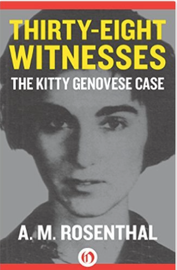

[Note: A central figure in promoting the narrative as one of urban indifference was A.M. "Abe" Rosenthal, in 1964 the city editor of the Times. In the months after the crime he published a book, Thirty-Eight Witnesses: The Kitty Genovese Case, that chastised those he said had provided the victim no aid. An interview that Bill Genovese did with Rosenthal before his death in 2006 is part of The Witness].

JS: The other thing I think [to consider about] this story is Abe Rosenthal, who was then the city editor of the New York Times but he went on to become the executive editor... and had a very distinguished career. He had been a journalist in Europe-- he had been a foreign correspondent and had come back to run the metropolitan desk -- and he wrote a seminal piece about Auschwitz. He was very shaped by the Holocaust and I think in some respects the [Genovese] story speaks to notions of who are we? The silence [i.e. that permitted the Holocaust to happen]. And ironically what Bill finds out in the course of the film is that a number of people who actually lived in the neighborhood were actually Holocaust victims. So there's a kind of subtext. In that respect the story spoke to many.

NFF: What was most difficult for you to film? Perhaps those times when Bill is meeting with his surviving siblings and they're almost pleading with him to let it go because they're in pain over the fact that he is pursuing this so diligently.

JS: The most difficult for sure was being in the vestibule where Kitty died, being alone with Bill. I'm not on camera, but I'm sobbing off camera watching him in the vestibule and knowing that the course of his life and his family's life in a sense unraveled as a result of what took place in that vestibule that night. So that's incredibly painful. But, and this is important, what Bill is doing in the film is reclaiming his sister's life from her death. And I was aware of that. I hadn't known at the beginning just how much Kitty's life had been erased, not just to all of us but actually to her own family. And I was aware that Bill was reversing history in the sense of reclaiming this remarkable 28-year-old's life from her death, not just for all of us but most importantly for all of his family... They [the Genoveses] have not spoken with anyone [in the media] for 50 years. They maintained silence on what happened that night. It's the most public story but the people who actually lived through it haven't talked about it. |

AuthorMatthew Carey is a documentary filmmaker and journalist. His work has appeared on Deadline.com, CNN, CNN.com, TheWrap.com, NBCNews.com and in Documentary magazine. |

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

Proudly powered by Weebly

- Home

- News

- Videos

-

Galleries

- 2019 Tribeca Film Festival

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival

- 2019 SXSW Film Festival

- SXSW 2018 Gallery

- 2019 Sundance Film Festival

- Outfest 2018 Photo Gallery

- Outfest 2017

- Sundance 2018 Photos

- 2017 LA Film Festival

- 2017 Cannes Film Festival

- Tribeca Film Festival 2017

- SXSW 2017 Gallery

- 2017 Berlin Film Festival

- Sundance 2017 Gallery

- 2016 Los Angeles Film Festival

- Cannes Film Festival 2016

- SXSW 2016 Gallery

- Berlinale 2016 Gallery

- Sundance 2016 Gallery

- Filmmaker Gallery

- About

- Contact

RSS Feed

RSS Feed